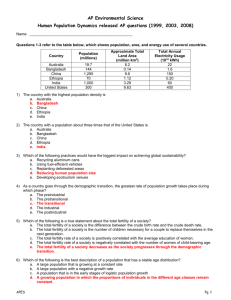

Seven Billion and Growing: A 21st Century Perspective on

advertisement