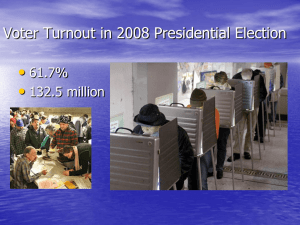

Voter Turnout Rates from a Comparative

advertisement