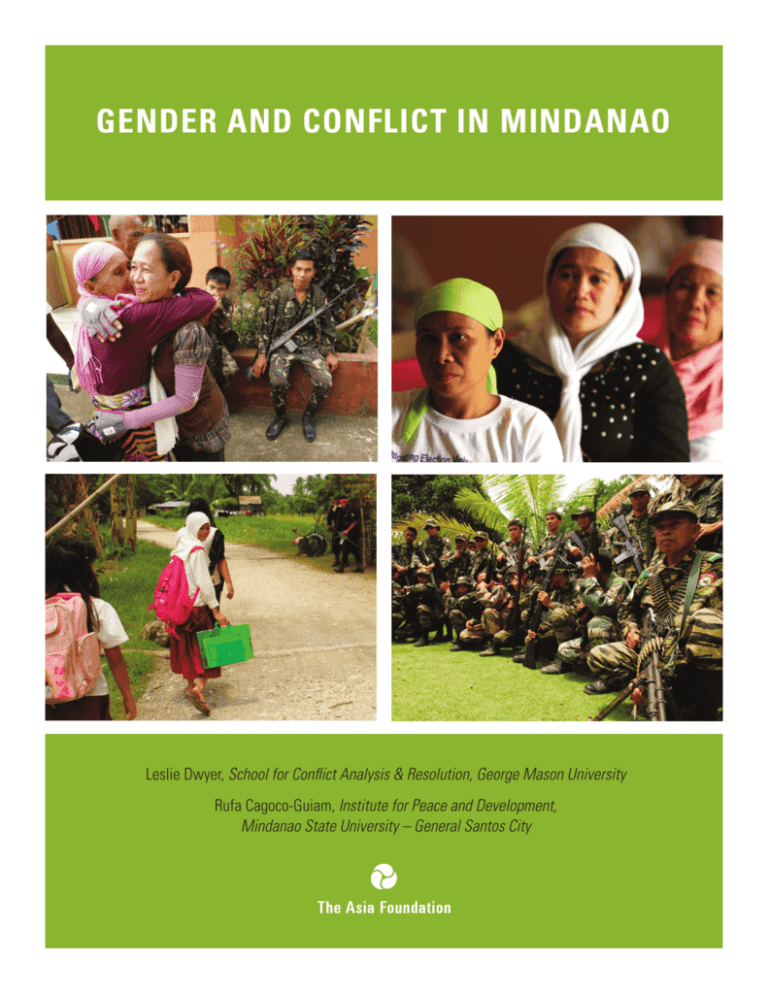

Gender and Conflict in Mindanao

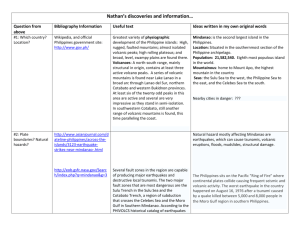

advertisement