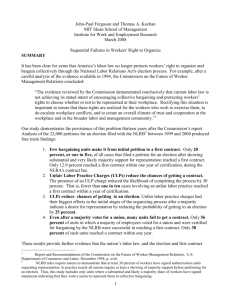

A Case for Structural Reform of the National Labor Relations Board

advertisement