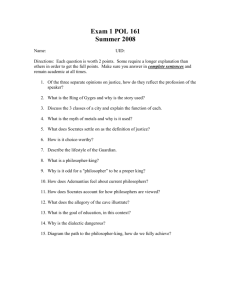

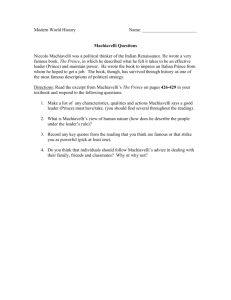

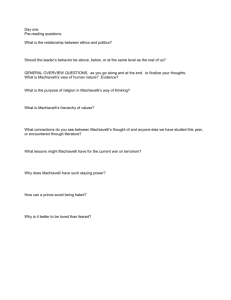

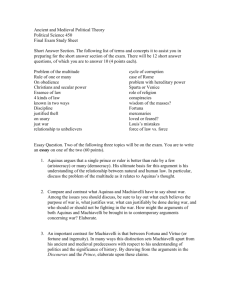

Machiavelli's republican political theory

advertisement