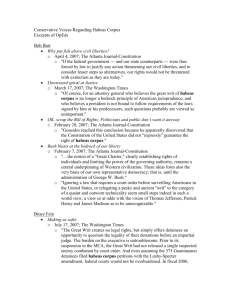

world habeas corpus - Cornell Law Review

advertisement