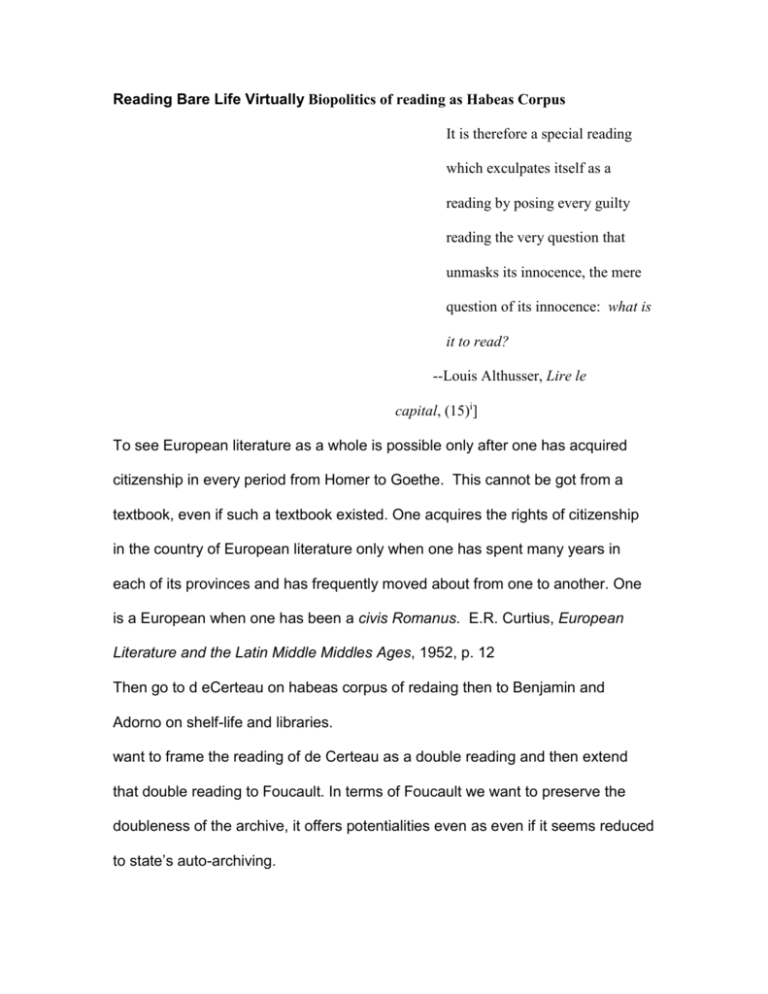

Reading Bare Life Virtually Biopolitics of reading as Habeas Corpus

advertisement

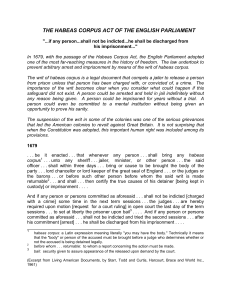

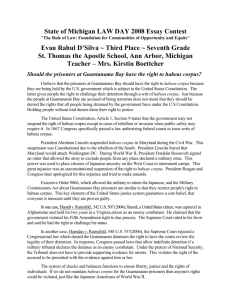

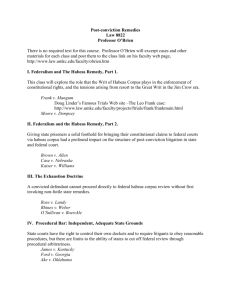

Reading Bare Life Virtually Biopolitics of reading as Habeas Corpus It is therefore a special reading which exculpates itself as a reading by posing every guilty reading the very question that unmasks its innocence, the mere question of its innocence: what is it to read? --Louis Althusser, Lire le capital, (15)i] To see European literature as a whole is possible only after one has acquired citizenship in every period from Homer to Goethe. This cannot be got from a textbook, even if such a textbook existed. One acquires the rights of citizenship in the country of European literature only when one has spent many years in each of its provinces and has frequently moved about from one to another. One is a European when one has been a civis Romanus. E.R. Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle Middles Ages, 1952, p. 12 Then go to d eCerteau on habeas corpus of redaing then to Benjamin and Adorno on shelf-life and libraries. want to frame the reading of de Certeau as a double reading and then extend that double reading to Foucault. In terms of Foucault we want to preserve the doubleness of the archive, it offers potentialities even as even if it seems reduced to state’s auto-archiving. Bring in de Certeau here as away of rethinking his notion of reading as sovereignty in order to make our book intelligible to history of the book people. Lefebvre + Chartier + Agamben equals Biopolitics of reading We should try to rediscover the movements of this reading within the body itself, which seems to stay docile and silent but mines the reading in its own way: from the nooks of all sorts of “reading rooms” (including lavatories) emerge subconscious gestures, grumblings, tics, stretchings, rustlings, unexpected noises, in short wild orchestrations of the body. But elsewhere, at its most elementary level, reading has become, over the last three centuries, a visual poem. It is no longer accompanied, as it used to be, by the murmur of a vocal articulation nor by the movement of a muscular manducation. To read without uttering the words aloud or at least mumbling them is a “modern” experience, unknown for millennia. In earlier times, the reader interiorized the text; he made his voice the body of the other; he was an actor. Today, the text no longer imposes its own rhythm on the subject, it no longer manifests itself through the reader’s voice. This withdrawal of the body, which is the condition of its autonomy, is a distancing of the text. It is the reader’s habeas corpus (175-176). By the way, also came up with this move on the History of the Book (in Theory). Flatlining the Book Historians of the book already assume a theory of reading, which they reduce to a functionalist pragmatics book use, and this unarticulated and untheorized default of use (in place of reading) determines how these same historians “read" the physicality of the physical / so-called material book. Putting the text apart from the book, the paratextual "parts" of the book go missing as such or are understood only as functional. Book production is subdivided into the books parts (as an assemblage process) but the assumption is that (a) the text is whole (whether or not it contains fragments or not is irrelevant; the form of the text becomes irrelevant--hence to the no need to read practice). They operate like file clerks who did not read what they filed. They offer up an anatomy lesson of the material text even as they misrecognize the corpus (things like glue, for example, or seals), reducing all of its life functions to a kind of EKG biobibliofeedback model. They (don't) read the book. They just flatline it. (Pun on flatline means that book history as a field reverts to what Vismann calls the earliest model of filing, continuous recording, on automatic--a continuous loop of a line. Extracts (and some comments) from the General Introduction of The Practices of Everyday Life In reality, the activity of reading has on the contrary all the characteristics of a silent production: the drift across the page, the metamorphosis of the text effected by the wandering eyes of the reader the improvisation and expectation of meanings inferred from a few words leaps over written spaces in a n ephemeral dance. But since he is incapable of stockpiling (unless he writes or records), the reader cannot protect himself against the erosion of time (while reading, he forgets himself and he forgets what he has read) unless he buys the object (book; image) which is no more than a substitute (the spoor or promise) of moments “lost” in reading. (xxi)ii Foucualt’s Pharmacyiii i Althusser’s deconstructive impulse in the ISA essay in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, the “continuous reading process” as the repressed part of the essay no one ever acknowledges. ii Pierre Bayard takes this idea further (even if you buy the works, you still forget the) in How to talk About Books You Haven’t Read. (The chapter on Montaigne is the best one.) iii Foucault on acid (LSD) misses orliteralizes the rug that is reading.