Innovation: Journal of Creative and Scholarly Works

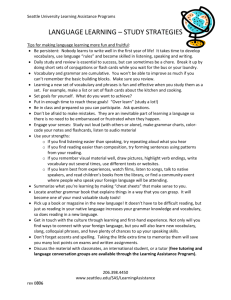

advertisement