Resource Portfolio The Big Bang Theory

advertisement

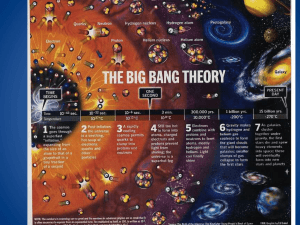

Resource Portfolio The Big Bang Theory Cheetahs - Group A Acheson, M. Brunelli, B. McCann-Wood, S. Rafraf, B. Contents 1. Summary ...................................................................................1 Brunelli, B. 2. Reviews 2.1. Textbooks .......................................................................2 Brunelli, B. 2.2. Worksheets .....................................................................4 Rafraf, B. 2.3. ICT .................................................................................6 Acheson, M. 2.4. Videos ............................................................................8 McCann-Wood, S. 3. Appendix 3.1. Worksheets ....................................................................10 3.2. Review Criteria ...............................................................14 3.3. Record of meetings and discussions ...................................15 1. Summary The Big Bang theory is a fascinating branch of physics which is sometimes undervalued because it is taken for granted and not given enough significance. Even though the Big Bang theory is approached only in Key Stage 4 in the new National Curriculum (Physics - Space Physics – History of the Universe), we chose to critically evaluate a range of resources suitable also for Key Stage 3. In particular, we decided to consider the use of textbooks, worksheets, ICT and videos. We decided to exclude practical activities, because the few we found were not relevant to our criteria (see Appendix). By using the set of resources we analysed, we aim to show the different models regarding the history of the Universe, in order to achieve not only a scientific understanding of the topic, but also to promote creative and critical thinking in our audience. As trainee science teachers, we would like to give scientific points of view, but also religious, philosophical and contrasting ideas, in order to discuss and argue who we are and what our purpose is in the Universe. The Big Bang theory is a fantastic source of discussions and ideas, and it could easily boost enthusiasm in a large range of students due to its potential overlap into many other subject areas. Our aim is to teach the Big Bang theory using a mixture of resources that cover as many styles of learning as possible. Textbooks could be used autonomously at home (as homework) or in the classroom with the support of the teacher, in order to develop literacy skills. The textbooks we have chosen offer good support, and could be strengthened by using selected worksheets alongside them. By using these resources, we can identify and address misconceptions in a pedagogical way. When we think about teaching science to students born in the 21st century, we must adapt our resources to their preferences on how to learn. For this reason, videos and ICT could potentially be the most engaging resources, delivered by experts within the field of physics. However, our textbooks and worksheets support a visual-spatial learning too, in addition to a linguistic approach. Our resources could stimulate whole-class or group discussions, so that the students are able to discuss issues between themselves and learn from one another. We now understand that, in order to inspire a broad understanding of science, we could use different resources in different parts of the lesson. We could choose to use a video as a starter to create intrigue and interest, a worksheet as a plenary to give opportunities to assess learning, and ICT resources as a main classroom activity. By using our resources, we aim to promote an independent and active learning, which can give students the tools to argue and analyse not only the Big Bang theory, but also other school-related or real-world issues. 1 2. Reviews 2.1. TEXTBOOKS Brunelli, B. Introduction Textbooks are a firm point of reference for students and teachers. Science textbooks, in particular, are fundamental for the development of scientific literacy skills, a scientific language and scientific method. Teachers may use textbooks to improve their knowledge and to find inspiration and ideas; students may use textbooks not only during science lessons, for reading and doing exercises, but also at home for individual study. Even if a textbook is not as interactive as a video or a practical activity, it could be engaging thanks to the use of different colours, highlighted keywords, diagrams and concept maps. I have decided to choose two books in particular, “Physics for You” and “Advanced physics”. I chose them based on their approachability, engagement and accuracy of knowledge. Despite the different level (GCSE and A), in both textbooks the scientific language is supported with examples, glossary, and visual intelligence is promoted with diagrams, drawings and pictures. Textbooks “Physics for You – Revised national curriculum for GCSE” by Keith Johnson (first published in 1978) has an attractive cover and an appealing title, as it refers directly to the reader. The Big Bang theory (page 166) is explained with the use of drawings, along with a diagram of the spectrum of light and the possible futures for the Universe. A balloon model with a clear figure of two men blowing up the balloons is used to explain the movement of the galaxies, which is practical and straightforward. The textbook’s appearance is enjoyable, with an extended and creative use of colours, diagrams and graphs. The vocabulary used is approachable, simple and concise, with stressed keywords. However, some ideas are too simplified and not explained in sufficient detail (e.g., “The red shift is like the pitch of a police-car siren going lower as it races past”). “Physics for You” certainly appeals to middle sets and support-level GCSE, but it may not be challenging enough for the top ones. In page 167 there is a paragraph called “The search for life in the Universe”, a topic which could create interest in students, and the diagram which follows (“Your place in the Universe”) gives the students a global idea and an external point of view of our purpose in the Universe. This is particularly engaging in science as, when analysing a particular science topic, we often lose perspective within the broader interpretation of nature. Other ideas of the origin of the Universe are also given, for example the Steady State theory (page 369), which make it clear we only have theories rather than certain, defined knowledge on the origin of the Universe. This textbook could be used independently by students in a classroom for the development of reading skills because DART activities could be easily used. In the textbook we also find a section on careers in which physics is considered essential or an advantage (page 388). Also, pictures of men and women of many cultures are shown in the next page, promoting equal opportunity and inclusion (which is 2 surprising, as this textbook is relatively old). Students may be motivated by the fact that they can easily see the role of physics in many interesting jobs. On the other hand, students should be stimulated by the idea of the importance of science as a subject that shapes and forms the citizen, rather than just use science as a tool to get an interesting job. The textbooks offer great support: we find exam-like questions and revision checklists offered throughout the textbook, alongside hints and tips. However, the questions at the end of the Big Bang theory chapter (page 173) are in a “conservative” style and do not promote students’ creativity. I personally would be interested in questions like “Do you believe in the Big Bang Theory?”, or “Do you have any other ideas about how the Universe could have been created?” “Advanced physics” by Steve Adams and Jonathan Allday is an AS and A level book for the main examination boards (AQA, OCR, Edexcel, WJEC, and CCEA). First published in 2000, it is a more recent book than “Physics for you”. The textbook is well organized, with a neat contents list at the beginning, an index at the end, objectives at the beginning of every chapter, bold keywords and diagrams alongside each paragraph. In chapter one (page 12) there is an explanation of how physics can explain everything: in the paragraph What?, the first line says: “If you ask what something is, a physicist will explain it in terms of something else, for example […]”. As this goes on, the book pleasantly refers to the teacher as a “she”, which is a very pleasant message to start a book with: “Ladies, this book is for you too!” In the following page there is a diagram showing the unification of physics, with all the branches connected, and with hypotheses for new theories, which gives the idea of physics as a “science in progress”, rather than something we have to passively understand. The Big Bang theory comes up many times throughout the textbook, but the main chapter is number 12, called “The physics of space”. In “The expanding Universe” chapter (page 549) I have found paragraphs starting with engaging questions: “Before the Big Bang?”, “Open or closed Universe?”. In the sub chapter 12.23, the objectives are specifically related to the Big Bang (Cosmology and particle physics, the Big Bang, background radiation); however, because the Big Bang theory is being mentioned many times before, the reader has already had a smattering of ideas on the topic. In the sub-chapter 12.24, called “Particle physics and cosmology”, the Big Bang theory is analysed in depth, with detailed steps, calculations and temperatures (the textbook also supports numeracy skills). The exercises are still exam-like questions and useful because of a wide variety of different questions for each examination board, but again not much space is given to students’ own ideas about the Universe. I think “Advanced physics” is a valid wide-ranging textbook, useful not only for A level students, but also for teachers who teach physics to a GCSE audience; it is then up to the teacher to adapt the advanced language into a more simple one. 3 2.2. WORKSHEETS Rafraf, B. Introduction The Big Bang Theory can be a very conceptually challenging topic. The topic is however broader than just the 'one theory' as people might think. There are several different subtopics and pieces of evidence, each conceptually different to each other. Understanding of the theory is accessible at several different levels. Some complicated ideas such as, the wave-particle nature of light, the Doppler Effect, cosmological length and time scales are discussed in schools in relation to the Big Bang theory. These subtopics build on each other conceptually. In this situation assessment for learning is vitally important. Worksheets are commonly used in an assessment for learning purpose. A circulating teacher can view the responses of their pupils and, with questions written down, pupils have a clear idea of what they are learning about and what they should know. Worksheets are a useful method of pupil-teacher communication. They allow the pupils to be individually engaged while the teacher addresses individual pupils. Worksheets however are very fixed in their method of communication and don't offer the dialogue which is required in the classroom. This fixed nature is inconvenient when dealing with such a conceptual topic as the Big Bang theory as pupils' understanding could be misguided in a manner of ways and fixed questions may not get to the root of a misconception. The topic is often approached with an historical focus and told as a story. Teaching this topic in this way is a good way to show an example of 'how science works'. Theories may be compared according to evidence that is observed. This is also a great example of a paradigm shift in the scientific world, however the risk of telling it as a story in this way is that it remains superficial as a story. By not daring to approach the actual change in thinking, one is doing a disservice to the story, masking the excitement which is the new way of seeing the Universe. Worksheets I have chosen the Worksheet 1 (Big Bang Poster Questions by Damian McGinn) as it tries to address the misconceptions one by one. The concept cartoon approach is certainly warranted in a topic such as this, however allowing pupils to make their own cartoons would give the teacher much more information of the pupil's level of understanding. This full concept cartoon treatment would take significant lesson time, this choice of cartoon activity is more time efficient. This worksheet would be used towards the end of a lesson to consolidate and assess learning, as opposed to a creative concept cartoon which is more suited to assessing the prior knowledge of pupils. The accuracy of knowledge is refreshingly accurate, though this is more conceptually difficult. The target audience for this worksheet is key stage 4, and while the pitch is conceptually difficult, it exposes the pupils to the paradigm shift in thinking. The sheet addresses the notion of space expanding, rather than the simplified, misconception reinforcing 'Universe expanding'. Because of the unintuitive nature of the topic it will 4 challenge all pupils' previous conceptions, the cartoon approach is vital. I think this is a very good resource as it, as well as coving the historical story, supports pupils in a very challenging conceptual conflict. It is these conceptual conflicts which are at the crux of modern physics and indeed one of the purposes of school education is to train future physicists. Worksheet 2, imaginatively named 'Big Bang Worksheet' is entirely different in its approach. The worksheet lists a series of questions summarising the evidence for the Big Bang theory. The target audience of this worksheet is key stage 4. This worksheet is pitched at an easier level than the previous one. It will be accessible to most pupils as it is possible to simply recall the answers. It does not test conceptual understanding, only the knowledge of facts. This worksheet is suited to very quick progression through the curriculum, where learning outcomes are facts to be learned. This worksheet would best be used as an end of topic recap of key ideas, it is better suited to revision rather than learning. This worksheet is suited for use as a tool of assessment. Worksheet 3 is my final resource, which focusses on the social, moral, spiritual and cultural (SMSC) aspects of the Big Bang theory. The theory is contentious as it proposes an alternative to religious teachings of intelligent design. The worksheet (Big Bang Theory by J Bennet) poses questions related to the Big Bang theory and its relationship with the idea of an intelligent creator. It poses different viewpoints on what the theory implies and shows the room for different beliefs within the bounds of scientific evidence. This worksheet may be accessible to pupils of a religious disposition. The worksheet is actually found classed under religious studies, however I feel that the religious aspect of the Big Bang Theory could and should be mentioned in teaching the topic in science. It gives pupils otherwise disengaged a forum for discussion, This worksheet does exactly that as it promotes thinking about the issue and debating with peers, this is a great example of the development of non-science specific skills in teaching the subject of science. The worksheet shows a mild bias towards religious conclusions by the wording of the cartoon, but this could be alluded to in class as a further discussion point. In conclusion, the worksheets I would most likely use in teaching this subject are the first and third, because I feel it is important that pupils be exposed to the unintuitive paradigm-shifting view of space which this topic can bring, as well as the SMSC aspects of the topic. These two worksheets require the pupils to think, both in different ways. They achieve much more than a simpler assessment driven worksheet. 5 2.3. ICT Acheson, M. First Resource: “The Big Bang”. Content by Angela Taylor of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory. Animated by Damian McGinn on Prezi. Link: http://prezi.com/q3lvq7aclqvy/the-big-bang/ This resource is an animated presentation consisting of a large “poster”, with sections within it that the user can zoom in on for greater detail. The author of the content is Angela Taylor of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory, a well-respected research institution. Thus, there can be little doubt as to the accuracy of the information provided, as the author was a researcher in astrophysics at the time of writing. However, there is no content within it regarding the philosophical or religious controversies of the Big Bang theory – this limits its usefulness in the “super-diverse” classrooms that exist in the UK today, where inclusive discussion is beneficial for all. In terms of quality of content, the information given is accurate and well laid-out, but has simple spelling typos within it which should be corrected before use. There is also an animated demonstration of cosmological red shift - what happens to electromagnetic waves within the context of an expanding Universe. This is particularly useful as it gives a clear visualisation of what happens to the light that is emitted by galaxies as space expands in all directions, a potentially confusing idea which is integral to the Big Bang theory. The interactive nature of it also means pupils could move back and forth between sections at will if they wanted to re-read parts of the resource. The presentation is publically available on the Prezi website, which means it is easily accessible by all pupils, at home or in school. It is also not technologically demanding, lowering any potential barrier to entry for both pupils and teachers. Due to this, it would be possible to get pupils to go through the presentation as a homework prior to the main lesson on the Big Bang theory. It could also potentially be used as a basis for an entire lesson on the topic, but care would be required to prevent the lesson turning into a lecture-style presentation by the teacher, with little room for pupil discussion. In conclusion, I believe this is a good IT resource, but one that would require some editing and the addition of religious and philosophical arguments to be universally useful. It would be most suited to independent study rather than a basis for a lesson due to its interactivity. Second Resource: “The Big Bang Time Machine” by the Association for Science Education. Link: http://resources.schoolscience.co.uk/PPARC/bang/bang.htm This resource is an interactive, animated timeline of the history of our Universe, based on the Big Bang theory. It is modelled as a time machine that the user can pilot to move forward or back in time to see what occurred at various times in the history of 6 the Universe. Due to its interactivity and animation, it would likely engage the pupils more if they were able to explore it themselves on a computer, rather than just being shown it on a projector. As the resource is freely available online, and only requires an internet browser to work, it is easily accessible by anyone with a basic computer and internet connection. However, the animation looks and feels quite dated, which may put off pupils who are likely used to higher-quality media and 3D effects. The content is presented factually and neglects any scientific, philosophical or religious debate on the matter, similar to the first resource. As a result, the resource would be more suitable as a pre-lesson homework to give the pupils a good grounding in the details of what our Universe was like in the past, according to the Big Bang theory. However, it does not give any history, reasoning or evidence of how the actual theory behind the Big Bang can account for this sequence of events, nor does it make any mention of the observations made by scientists which resulted in the formulation of the theory. Thus it is limited in scope, detail and evidence, and therefore limited in its utility as an aid to teach about the Big Bang theory. Third Resource: “Evolution” by John Kyrk and Dr Uzay Sezen of the University of Georgia. Link: http://www.johnkyrk.com/evolution.html This resource is an animated, interactive timeline in which the user is free to move to any point in the history of the Universe to see information on what was occurring at that point in time, according to the Big Bang theory. It has interactive links embedded throughout the timeline, which bring the user to external sources of additional information on a particular topic. These links expand the scope of the resource to include historical, religious and philosophical aspects of the Big Bang and, as they are optional, it allows the user to access as much or as little information on each topic as they desire. The breadth of information within the resource is very wide, and may overwhelm younger pupils. For older pupils, however, it would likely engage them strongly as the information is presented in a very entertaining, accessible and elegant way. It could be used as a basis for a lesson if the teacher was restrained in how much of the timeline was covered within the lesson due to the sheer volume of information contained within it. However, a better use of this resource would be as the basis of a short project for pupils, where they could explore the resource independently and then choose aspects of it to write about, then present the findings to the class. The accuracy of the information within this resource is excellent, and gives a great over-arching view of the Big Bang theory and how it can account for the Universe as it is today. Also, due to the breadth of content, it would allow for significant overlapping and linking of the Big Bang theory into many other aspects of the science curriculum, from creation of the elements of the periodic table up to evolution and beyond. 7 2.4. VIDEOS McCann-Wood, S. Introduction “Where has the Universe come from?” This is one of the biggest questions that humans have ever asked themselves. I think that with this in mind it is very important that while teaching the Big Bang theory we attempt to not only pass on the most current scientific information but also the enormity of the question and the amazement surrounding it. With something as complex as the Big Bang I think that it is very important to highlight that the theory we have at present is not the end, that there is more we don’t know. Students should be given information as to how observations allowed the theory to be developed and we should teach our students to continue to be curious and critical of what we believe we know so far. Imagination is a crucial part of understanding science (Driver, 1983) and I think that, especially with a concept as enormous as the Big Bang, video can be a very useful aid in helping pupils to visualise the ideas involved and therefore understand it better. I will critically analyse three different video resources (referenced below) that could be used in class to help teach the Big Bang and give some ideas of how they could be used. Video 1 – “Wonders of the Universe” This video is aesthetically pleasing, clearly presented with accurate and up-to-date subject knowledge. It is not particularly fast paced or dramatic, but I believe that the way the information is presented is thought provoking and easily understandable. This makes it engaging and accessible. The resource gives a very balanced view and isn’t biased. It doesn’t criticise any religious views, it merely states the observations scientists have made and what can be deduced from these. The video clearly states that the Big Bang theory is “the best scientific theory” that we have and explains the scientific observations and evidence that have led us to the theory. The video is quite zoomed in on one particular aspect of the Big Bang (red shift as evidence for the big bang). Understanding this aspect is crucial for understanding the theory and so this is a very useful resource. However, the video doesn’t have much of a visualisation of the Big Bang “explosion” itself, and I think that this would be useful for enabling a class to visualise the process. Therefore, if I were using this video I would use it alongside another video that provides this. The level is suitable for KS4 and is in keeping with the national curriculum which includes the topic of red-shift and expansion of the Universe. The video is quite short which is good as hopefully pupils’ attention wouldn’t be lost, but whilst watching the video I would ask students to do a task so as to maintain concentration. I would ask them to write down a list of the facts and observations that have allowed us to formulate the Big Bang theory. Video 2 – “History of our Universe” I have mixed feelings about my second video. It is not from an official source and so I debated whether to use it. However, I did some research into the person who created the video (a former science journalist) and also the information he provides and deemed it reliable. I really like the way this video shows the history behind the 8 development of the theory. This gives the video an interesting real life feel and would make it more accessible to students. They would be able to see how individual people have made observations, developed their ideas and added to the ideas of others. It also highlights that there is more to find out which I think may encourage students to feel involved and think about their own ideas. The video discusses the feeling of wonder that pushed and still pushes people to try to discover more about the Universe and I think this would help stimulate students’ interest. Disadvantages of the video are that it is visually quite simple. It is not really a video but more a series of images. The delivery of information is also a little dry which may not keep some students engaged despite the interesting content. There is also quite a lot of information to take in. I am unhappy with a very small section from the beginning and the end in which the speaker makes a rather unnecessary and slightly derisory comment about people trying to guess how the Universe was created rather than using real observations. I think some religious people could feel offended by this comment and therefore I would probably miss these parts out. Whilst watching I would ask students to focus on the historical aspect and make notes on the different stages of discovery that took place. Video 3 – “Stephen Hawking - The Big Bang” I chose this video because it shows a very good visualisation of the Big Bang happening. I think that this is very important to include as it helps students to imagine the Big Bang which is crucial to understanding the theory. The video discusses some of the mind-blowing concepts such as before the Big Bang there was no time, light or space which is a thought that really helps to give that feeling of wonder so important to getting excited about science. The video does begin to get a little bit complex for a KS4 class towards the end. Therefore, I would decide whether or not to play the whole clip based on my assessment of the class’s ability. I believe that the source is reliable as the clip comes from a series by Professor Stephen Hawking. The video makes a point to be as accurate as possible, explaining to viewers that although the video shows an “explosion” in reality you wouldn’t have seen this as light didn’t exist yet. The video appears un-biased, up-to-date and there is nothing in it that any religious groups could reasonably take offence to. While watching the video I would ask students to note down one new thing that they have learnt or one thing that surprised them. References Driver, R. (1983) The Pupil as Scientist? Milton Keynes: The Open University Press. Video 1: BBC (2011) Wonders of the Universe (class clips) [Online]. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/learningzone/clips/the-big-bang/12236.html Video 2: Peter Hadfield (uploaded 2009) History of Our Universe Part 1 (for schools) [Online]. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uihNu9Icaeo&list=FLHN_E5MmNZmz_ZvtjEXNA7Q Video 3: (uploaded 2011) Stephen Hawking - The Big Bang [Online]. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gs-yWMuBNr4 9 3. Appendix 3.1 Worksheets Worksheet 1 10 11 Worksheet 2 The Big Bang Theory 1) State 2 facts about the present state of the Universe. 2) How does an expanding Universe provide evidence for the Big bang theory? 3) What is the Cosmic Microwave Background radiation? 4) What other evidence is there for the Big Bang theory? 5) What could you say about the future of the Universe if the galaxies were slowing down? 6) Galaxy X has a larger red-shift than galaxy Y. a) Which galaxy, X or Y, is nearer to us? b) Which is moving away faster? c) The light from the Andromeda galaxy is not red-shifted. What does this tell you about Andromeda? 12 Worksheet 3 The Big Bang Theory It is possible to use the Big Bang Theory to support the design argument and also to attempt to prove that God doesn’t exist. I do not believe there was an original cause to the universe. I believe that the Big I believe that God was the original cause of the universe. He was the one who started it all off. I believe he did this through the Big Bang. Bang came about on its own without the need for a cause. 1. How might someone use the Big Bang theory to support the design argument? 2. How might someone use the Big Bang theory to argue that God does not exist? 3. Copy and complete these sentences in your book. The design argument is…….. The design argument is also known as……… Many theists believe in the Big Bang theory because……… 13 3.2. Review Criteria 1. General aspects: 1.1. Accuracy of knowledge: Is the knowledge presented in a correct way? May the resource lead to misconception? If not exact but very engaging, is it worth the risk? 1.2. Bias: Is it a reliable resource? Is it influenced by society, politics or culture? 1.3. Age: How recent is the specific resource? Which are the consequences of this? 1.4. Relevance: In which ways is the resource relevant? 1.5. Religious inclusivity: Are there contrasting religion beliefs? 2. Approachability: 2.1. Pedagogy: Is the resource using an accessible vocabulary? 2.2. Level of content: Is the content suitable, too sophisticated (discouraging, too challenging) or too elementary (boring, unexciting)? 3. Practicality: 3.1. Timing: How much of a lesson would the resource take? 3.2. Logistic: Would the school have the features to perform it? 4. Engagement: 4.1. Interactivity: How much interest is stimulated? Is the material thoughtprovoking? How can students interact with it? 4.2. Appeal: How is the resource presented? In which ways does it engage the students? 4.3. Thinking: Is it possible to use the resource to promote peers discussions? 5. Relevance to the National Curriculum: 5.1. Learning outcome: What will the students be able to take away from using the resource? Is the learning outcome useful in terms of government demand? 14 3.3. Record of meetings and discussion Our group had its first meeting on Monday 21 st October afternoon. Following meetings then took place every Monday since, for about an hour after King’s College sessions, after we decided it was better to share ideas by discussing them directly. The meetings had been arranged mainly privately, by communicating through Facebook (in our group Cheetahs Group A – Resource Portfolio), or via mobile phone. First meeting arrangement and notes (extracted from Keat’s): Resources Portfolio - Cheetahs - Group A (The Big Bang Theory) by Bianca Brunelli - Saturday, 19 October 2013, 5:17 PM Dear Shona, Mark and Bijan, We are meeting on Monday 21st October after the seminar to discuss how to develop each topic (textbook, ICT, practical, worksheet). Re: by Shona Mccann-Wood - Sunday, 20 October 2013, 11:33 PM Hi Bianca, Monday is good for me, see you then. Re: by Bianca Brunelli - Wednesday, 23 October 2013, 11:07 AM Dear All, Here's our "outcome". We started from a good set of drafts and we ended up with a more organized list of criteria. Pictures and file to follow. Have a nice week at school! Bianca Re: by Shona Mccann-Wood - Sunday, 10 November 2013, 4:24 PM Great, thanks for uploading Bianca. Shona 15 16