ECO 209Y Macroeconomic Theory and Policy

advertisement

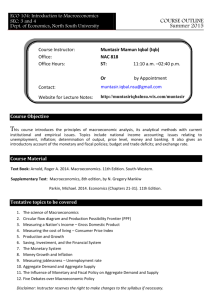

ECO 209Y Macroeconomic Theory and Policy Lecture 1: Introduction © Gustavo Indart Slide 1 Branches of Economics Microeconomics is concerned with the study of the choice problem faced by the economic agents: households and firms e.g., how the equilibrium price for a particular commodity is determined Macroeconomics is concerned with the study of the economy as a whole e.g., how the general level of prices is determined (and not the price of any particular commodity) © Gustavo Indart Slide 2 The Object of Macroeconomics How the general level of prices is determined? What determines the percentage of the labour force that is unemployed? What determines a country’s level of aggregate output or GDP? What determines the level of interest rates? What determines the foreign exchange rate? What determines a country’s balance of payments with the rest of the world? © Gustavo Indart Slide 3 The Rate of Inflation The inflation rate (π) is the percentage increase in the level of prices during a given period: π= P − P-1 P-1 where P is the current price level and P-1 is the price level at the end of the previous period. © Gustavo Indart Slide 4 Canada: Inflation and Deflation Source: P. Krugman, R. Wells and A. Myatt, Macroeconomics. © Gustavo Indart Slide 5 Canada: Inflation and Deflation January 2004 to September 2014 Annual Change on CPI © Gustavo Indart Slide 6 The Rate of Unemployment The unemployment rate is the fraction of the labour force that cannot find jobs: LF − N u= LF where LF is the size of the labour force and N is the number of employed workers © Gustavo Indart Slide 7 Canada: Unemployment Rate Source: P. Krugman, R. Wells and A. Myatt, Macroeconomics. © Gustavo Indart Slide 8 Canada: Unemployment Rate January 2004 to September 2014 © Gustavo Indart Slide 9 Aggregate Output (GDP) Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the value of all final goods and services produced in the economy during a given period of time Nominal GDP measures the value of output at the prices prevailing in the period the output is produced Real GDP measures the output at the prices of some base year © Gustavo Indart Slide 10 Canada: Growth in Aggregate Output Source: P. Krugman, R. Wells and A. Myatt, Macroeconomics. © Gustavo Indart Slide 11 Canada: Growth in Aggregate Output January 2004 to September 2014 Annual Real GDP Growth Rate © Gustavo Indart Slide 12 Canada: Growth in Aggregate Output Source: P. Krugman, R. Wells and A. Myatt, Macroeconomics. © Gustavo Indart Slide 13 Canada: Real GDP per Capita Source: P. Krugman, R. Wells and A. Myatt, Macroeconomics. © Gustavo Indart Slide 14 The Rate of Interest The nominal rate of interest (i) is the actual money interest charged on a loan The real rate of interest (r) is the purchasing value of the interest charged on that loan, that is, the real interest rate is the nominal rate (i) minus the rate of inflation (π): r=i−π © Gustavo Indart Slide 15 Canada: Prime Rate of Interest January 1970 to September 2014 © Gustavo Indart Slide 16 The Exchange Rate The exchange rate is the relative value of the currencies of two countries We will define the exchange rate (e) to be the value of one unit of foreign currency measured in Canadian dollars The exchange rate for US$ is today approximately e = 1.32 This means that the value of the Canadian dollar is today approximately 1/e = 0.76 i.e., Cdn$1 = US$ 0.76 The level of the exchange rate could be set by the Bank of Canada or be determined by market forces Bank of Canada sets the value of e fixed exchange rate system Market forces determine the value of e flexible or floating exchange rate system Bank of Canada intervenes in the market to avoid sudden jumps managed or dirty floating exchange rate system © Gustavo Indart Slide 17 The Exchange Rate between the Canadian Dollar and the U.S. Dollar Source: P. Krugman, R. Wells and A. Myatt, Macroeconomics. © Gustavo Indart Slide 18 The Exchange Rate between the Canadian Dollar and the U.S. Dollar January 2005 to September 2014 © Gustavo Indart Slide 19 The Balance of Payments The balance of payments is the record of all transactions of the economy with the rest of the world The overall balance of payments is the summation of the balance in two accounts: the current account and the capital account The current account records all the imports and exports of goods and services, investment income, and transfer payments The capital account records the capital flows, that is, investment and borrowing/lending © Gustavo Indart Slide 20 Canada’s Balance of Payments, 2010 Receipt Payment Balance 547,141 598,005 -50,864 Goods and services 476,086 507,844 -31,757 Investment income 61,794 78,230 -16,436 9,261 11,932 -2,671 156,883 107,176 49,707 Current account Transfers Capital account Statistical discrepancy © Gustavo Indart 1,157 Slide 21 Canada’s Current Account Balance as Percent of GDP January 1980 to September 2013, quarterly © Gustavo Indart Slide 22 Economic Policy Policy makers use mainly two types of policies to affect the economy: fiscal and monetary policies The government (Parliament) controls fiscal policy, while the Bank of Canada controls monetary policy The instruments of fiscal policy are tax rates and government spending The main instruments of monetary policy are changes in either the stock of money or the bank rate © Gustavo Indart Slide 23 Leading Schools of Thought There is a widespread belief that the government can and should take actions to influence key economic variables such as inflation and unemployment Economists don’t agree, however, on what measures will achieve the desired results The reason for this disagreement is that we don’t have any particularly compelling theory There are different schools of thought and the most important ones are the Monetarist, the Keynesian, the New Classical, and the New Keynesian © Gustavo Indart Slide 24 The Monetarist School Governments should have policies towards a limited number of macroeconomic variables (e.g., growth of money supply, government expenditure, taxes, and/or the government deficit) Governments should adopt fixed rules for the behaviour of these variables (e.g., a fixed rate of growth of money supply or balanced budget over a period of four or five years) Policy changes should be announced as far ahead as possible to enable people to take account of them in planning their own economic affairs © Gustavo Indart Slide 25 The Keynesian School They advocate more detailed intervention to “fine tune” the economy in the neighbourhood of full employment and low inflation Government intervention should be counter-cyclical Policy changes should not be pre-announced in order to deter speculation © Gustavo Indart Slide 26 The New Classical School The New Classical or Rational Expectations school assumes that markets are continuously in equilibrium (particularly the labour market) They also assume that expectations are formed “rationally”, that is, taking into account all the economically relevant information For this reason, expected government intervention cannot affect the real variables in the economy © Gustavo Indart Slide 27 The New Keynesian School The New Keynesians assumes that wages are not fully flexible as to always equate the demand and supply of labour They assume that wages are fixed during a period of time due to institutional constraints (e.g., minimum wage legislation or labour contracts) Due to these rigidities in the labour market, government intervention can most effectively affect the economic variables © Gustavo Indart Slide 28 Macroeconomic Models Economists use models to help explain real world phenomena Economic models represent simplifications of the real world They take into account only some “endogenous” and “exogenous” variables They also make assumptions about the behaviour of economic agents If some determining variables are left out or some behavioural assumptions are at odds with reality, then the model represents a distortion and not a simplification of the real world Different models help to explain the behaviour of the economy at different times and situations © Gustavo Indart Slide 29 Aggregate Demand The level of aggregate demand is the real value of the total demand for domestically produced goods and services The aggregate demand curve (AD) shows the negative relationship between the price level and the real value of the quantity demanded of domestically produced goods and services At each price level, the AD curve shows the value of output at which both the goods markets and the money markets are simultaneously in equilibrium (we’ll see this in more detail later on) © Gustavo Indart Slide 30 Aggregate Supply The level of aggregate supply is the real value of the output the economy can produce given the resources and technology available The aggregate supply curve (AS) shows the relationship between the price level and the real value of the quantity supplied of goods and services and its slope depends on whether we are referring to the short run, medium run, or long run The short run, medium run, and long run do not refer necessarily to different time-periods They refer rather to different situations the economy goes through over time © Gustavo Indart Slide 31 Aggregate Supply (continued) In the short run the level of output can vary without affecting the price level The economy is producing at less than full capacity and unemployment is high The AS curve is horizontal, and the aggregate demand determines the level of output In the medium run there is little or no excess capacity and unemployment is low, thus the AS curve has a positive slope © Gustavo Indart Slide 32 Aggregate Supply (continued) In the long run the level of output is determined by the productive capacity, and thus it is fixed at this maximum level Therefore, in the long run the aggregate supply curve is vertical at this maximum level of output Changes in demand can only affect the price level but not the level of output In the very long run the productive capacity of the economy increases and thus the vertical AS curve shifts to the right © Gustavo Indart Slide 33 The AS Curve AS P Medium-run Long-run Short-run Yfe © Gustavo Indart Y Slide 34