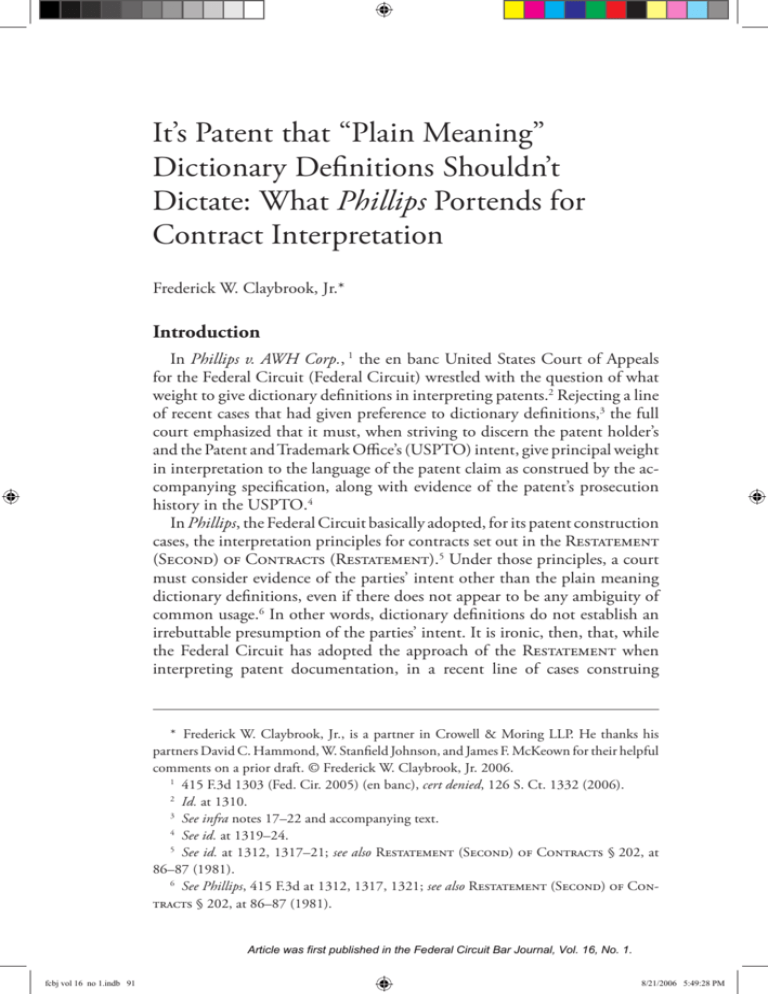

“Plain Meaning” Dictionary Definitions

advertisement