Historic Netsch Campus at UIC: A Walking Tour Guide

advertisement

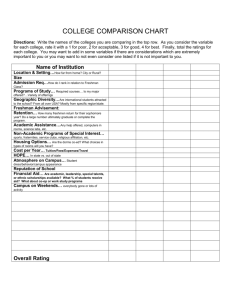

Historic Netsch Campus at UIC Table of Contents Tour Map 3 Introducing the Historic Netsch Campus at UIC 4 Campus Beginnings 4 Site Selection 4 “Instant Campus” 5 Campus Master Plan 5 Circle Forum 6 Stone Dropped in a Pond of Water 6 Granite, Concrete and Brick 6 Harrison and Halsted 7 Historic Artifacts 7 Harrison-Halsted Neighborhood 7 Neighborhood Protest 8 Architecture and Art 8 Field Theory 8 Walkway Remnant 9 Site of Turner Gate 9 Jonathan Baldwin Turner 9 Second-Story Walkways 9 Fate of the Walkways 10 Henry and Jefferson Halls 10 Block I Window Design 11 Connecting Walkways 11 University Hall 11 “Big Shoulders” Design 11 Rebecca Port Faculty-Student Center 12 Behavioral Sciences Building 12 Stevenson Hall 12 Lincoln, Douglas, and Grant Halls 13 Green Architecture at UIC 13 Richard J. Daley Library 13 Science and Engineering Offices 14 Taft, Burnham, and Addams Halls 14 Science and Engineering Laboratories 15 Science and Engineering South 15 Blue Island Corridor 15 Netsch-designed Fence 16 Chicago Circle Memorial Grove 16 Addenda 17 Tour Map AA STREET LIB A F LH B Jane Addams Hull-House Museum C LC E D POLK TH MORGAN STREET STREET Begin Self-guided Tour at Student Center East GH DH STREET SEO BH Parking Available at Halsted Street Parking Structure AH STREET SELE SELW MILLER CARPENTER VERNON PARK SH POLK TAYLOR STREET SES STREET I-90/94 JH HARRISON EXPRESSWAY UH BSB STREET HH I-290 UIC/HALSTED CTA STATION DAN RYAN HARRISON EXPRESSWAY HALSTED STREET EISENHOWER MORGAN STREET ROOSEVELT ROAD Campus Beginnings TAYLOR STREET Circle Forum Harrison and Halsted Architecture and Art Site of Turner Gate Second-Story Walkways Henry and Jefferson Halls University Hall Behavioral Sciences Building Stevenson Hall Lincoln, Douglas, & Grant Halls Richard J. Daley Library Science & Engineering Offices Taft, Burnham, & Addams Halls Science & Engineering Laboratories Science & Engineering South Blue Island Corridor Chicago Circle Memorial Grove Introducing the Historic Netsch Campus at UIC Welcome to the historic Netsch campus at UIC. This virtual walking tour introduces the modernist architecture found on the East Side of the University of Illinois at Chicago. Internationally acclaimed architect Walter Netsch at the Chicago firm of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill designed the campus between 1963 and 1968. In 1960, Chicago was one of only three major American cities that lacked a four-year publicly supported university. Thanks to the vision and determination of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, that changed just five years later, when the University of Illinois opened this campus to educate the children of working families right here in the city of Chicago. Located adjacent to a major city expressway interchange popularly known as “the Circle,” the new campus was named the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle. Circle welcomed its first students in February 1965. Though much has changed in the nearly fifty years since Walter Netsch was engaged as principal architect on the project, his remarkable vision for the campus is still evident in buildings and spaces all over the East Side of UIC. Images from then and now accompany our story. Campus Beginnings The story of the Chicago campus of the University of Illinois begins on Navy Pier at the end of World War II. With the GI Bill offering educational opportunities to large numbers of returning veterans, the university recognized the need for educating students in Chicago as well as Urbana-Champaign. In 1946 a two-year undergraduate program opened on Chicago’s Navy Pier. Students could spend two years taking classes at the Pier, but to complete their degrees they had to transfer downstate. Because many parents could not afford to send their children away to school, they lobbied for a university right here in the city. Site Selection Planning for a Chicago campus began in the mid 1950s, when a number of different sites, suburban and urban, were considered. The university chose internationally acclaimed Sites under considerationarchitect Walter Netsch at the Chicago firm of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill to create schemes for four possible locations: Miller Meadows in North Riverside, Garfield Park, Northerly Island, and the rail yards south of the Loop. Miller Meadows was the university’s first choice, while Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley favored a location in the city. In 1960 a bond issue passed earmarking $50 million for the construction of the Chicago campus. When the other Chicago sites were not available, Mayor Daley and university trustees announced the selection of our current location, which consisted at the time of 105 acres stretching south and west from the Harrison and Halsted intersection, just a mile to the west of Chicago’s Loop. 4 “Instant Campus” The University of Illinois at Chicago Circle was one of several “instant campuses” built in response to major growth in college enrollment following World War II. New York and California had even more ambitious schemes and created multiple campuses around the same time. Though just a single campus, UICC received more publicity than any of the others, in large part because of its architectural design, which was considered revolutionary at the time. The style, known as Brutalism, took its name from Campus constructionthe French béton brut, meaning raw concrete. Internationally in vogue from the 1950s to the 1970s, Brutalist architecture avoided polish and elegance. Practicality, economy, and user-friendliness were the principal aims of the stark, rectilinear style. Readily accessible materials such as concrete, brick, and stone were preferred. As soon as the first phase of construction was completed, the Netsch design received an award from the local American Institute of Architects chapter and a total design award from the National Society of Interior Designers. Architectural Forum magazine covered the developing campus extensively from 1964 through 1970. Campus Master Plan Working under extreme time and budget constraints, architect Walter Netsch developed a campus design concept based upon the urban setting, the size of the site, and a projected student population of 20,000, which increased to 32,000 in just a few years. The goal was a campus that could work at its initial size while growing quickly to its projected size. In its first five years, the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle was the fastest growing campus in the country, increasing from 5,000 to 17,500 students.To this day, it has not reached 32,000 students. To enable large numbers of students to navigate the new campus efficiently, Netsch elevated much of the movement and activity to the second story level. The unique “pedestrian expressway system” served as a structuring element for the visual and functional organization of the campus while introducing an interplay of levels. At its center, the raised walkway system converged on an immense second floor expanse of granite and concrete which connected to major buildings to the east and to the west. At the northern and southern entrances to campus, the walkways extended across major streets, allowing pedestrians to avoid traffic and enter the campus safely. 5 Circle Forum At the heart of the University of Illinois Chicago Circle stood a two-story classical amphitheater known as Circle Forum. This was the center of campus life, home to concerts, performances, student protests. Those traveling from one building to another passed through the area. A level higher, the roofs of the surrounding buildings formed a vast plaza called the Great Court, punctuated by seating areas known as exedras. Walkways at the second floor level tied this central structure to all the surrounding campus buildings. Only photographs remain to convey the remarkable architecture that once stood here. Circle Forum, the Great Court, and the walkways were all demolished in the mid 1990s after gradually falling into disuse and disrepair. Lack of climate control and difficulty of maintenance, especially in winter, were factors contributing to the university’s decision to abandon those elements of the Netsch design. Chicago architect Daniel P. Coffey was responsible for the redesign of the area as it appears today. Stone Dropped in a Pond of Water Walter Netsch’s unique campus design was based on the metaphor of a stone dropped in a pond of water. Buildings were grouped by function with the most important – the lecture centers – forming a close circle at the center. Classroom building clusters, anchored by the library to the west and the student union to the east, formed the next ring. Offices and laboratories were further removed from the center, and on the outermost ring to the south were the athletic fields. With the large buildings situated towards the outside, the central area was buffered acoustically from the noise of the nearby expressway. Inspired by classical motifs such as the agora, the marketplace in ancient Greece, the Forum and the lecture centers represented the center of learning, the place where students and their teachers gathered to discuss ideas. From there, learning extended outwards in all directions. “What happens between classes came to be regarded as being as important as what happens in classes,” said Netsch. His campus design facilitated “the meeting-in-the-corridor on a grand scale.” Granite, Concrete and Brick Netsch selected three sturdy materials – granite, concrete, and brick – which are repeated in structures throughout the campus. Solid granite from Minnesota quarries was chosen for its permanency and its ability to withstand the annual removal of snow and ice. Brick and concrete, both readily available at the time, could resist dirt or disfigurement. Netsch developed special 6 colors and sizes of brick as well as six different finishes for concrete. He utilized a relatively low strength reinforced concrete as a cost saving measure. The lecture centers illustrate Netsch’s use of granite and concrete. Visible below the roofline is a layer of granite a foot thick that forms the base of the building roofs. It is supported by “butterfly columns”, so named by the architect for the shape of the column capitals, which increase the area the columns are able to support. Precast concrete columns supported all the granite walkways linking the Netsch buildings. Those at ground level in the early years found themselves walking in what Netsch referred to as “a forest of columns.” Netsch designed columns of differing height and girth, depending on the load they were to carry. Harrison and Halsted The location of the new undergraduate campus was important to the city and the University of Illinois. The 105-acre plot of land on the city’s Near West Side was easily accessible by public transportation, including buses, trains, and a new expressway system. Its proximity to the circular interchange of three major expressways led to the original campus name: the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle. Historic Artifacts Set into the concrete between the flags at Harrison and Halsted is a modest granite plaque from the ground-breaking ceremony held October 17, 1963. It reads: “Just as universities make great cities, a great city makes a great university.” – Honorable Richard J. Daley, Mayor of Chicago. he chain-linked granite bollards in this location, featuring Walter Netsch’s “tiger tooth” design, lined the exterior walkways and stairwells of the Chicago Circle campus. Today they serve as a memory of our campus architect and the unique physical environment he created. Harrison-Halsted Neighborhood Before 1960, the concentration of Greek immigrants living and working along Halsted north of Taylor led Chicagoans to refer to it as the Greek Delta. The neighborhood stretching west along Taylor was Little Italy. In addition to these two large groups, the area was also home to Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and African Americans. Private homes, stores, cafés, and factories were all mixed in together here. Citizens saw an opportunity to improve the neighborhood and formed the Near West Side Planning Board, which succeeded in obtaining federal urban renewal money. But larger forces were at play, and to the dismay of Planning Board members, the money was ultimately used to clear the area for the new university. 7 Neighborhood Protest When the University of Illinois announced the selection of the Harrison-Halsted site, resident Florence Scala led much of the neighborhood in protesting the decision. Embodying the civic conscience of Chicago’s Little Italy, Florence Scala had developed her sense of social justice at nearby Hull-House, where she participated in classes and activities throughout her youth. As leader of the Harrison-Halsted Community Group, she fought the city every step of the way. Suits were eventually filed in both federal and state courts to prevent the project from going forward. In May 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case, clearing the way for construction of the new university. Large sections of the Harrison-Halsted neighborhood were demolished to make room for the campus, displacing significant numbers of people and businesses. In a small but important victory, Florence Scala and her followers succeeded in persuading university trustees to preserve the Hull-House and Residents’ Dining Hall, located at 800 South Halsted, as a memorial to Jane Addams. Architecture and Art The Architecture and Art building was built in 1967 during the second phase of campus construction. This was the Netsch’s first A and A footprintsattempt at Field Theory, his signature contribution to architecture. Only 40% of the building was completed; the classroom wings were never added. A large block of granite on the south side bears the name Architecture and Art. Field Theory Field Theory consisted of rotating simple squares into complex geometric elements radiating outward from central cores. In seeking to move beyond “the boredom of the box,” Netsch created imaginative but organically integrated spaces. The double helix served as the inspiration for the Architecture and Art building interior, translating to a helical path of open spaces where faculty and students could work side by side in a collaborative manner. 8 Walkway Remnant A solitary remnant of the second-story walkway system, an important element of the original campus design, has been maintained at the entrance to the Covered walkwayArchitecture and Art building. The sign bearing the building name now covers it completely. Measuring 200 feet in length, this particular walkway was unique in that it was constructed of steel, not granite, and it was the only screened walkway on campus. The box truss design made it possible to lower the structure into place over the brick-enclosed Commonwealth Edison property just Com Ed substation west of Architecture and Art. Behind the south wall of the enclosure, the Com Ed building still stands, although the electrical substation Walkway remnantis no longer in use. Original Netsch-designed gates provide access to the interior. Site of Turner Gate A tall concrete pillar bearing the name UIC, once attached to the second-story walkway in this location, marks the site of Turner Gate. When the Circle campus opened in 1965, an eight-foot-high brick wall, punctuated by eight iron gates, surrounded most of the area bounded by Harrison, Halsted, Taylor, and Morgan. Turner Gate was the entry point for those reaching campus via the “L.” Although outer walls and gates are traditional elements of university design, the surrounding community expressed dismay to find the new University of Illinois campus walled off from the city it was built to serve. Before long the gates fell Campus wallinto disuse, the walls began to come down, and university buildings sprang up beyond the original boundaries. When the gate in this location disappeared, so did the name. Only remnants of the original walls remain. Jonathan Baldwin Turner Turner Gate was named for Jonathan Baldwin Turner, whose appeal in 1850 for a “state university for the industrial classes” led to the Land Grant Act of 1862 and the formation of the University of Illinois in the years that followed. UIC is an urban descendant of the land grant tradition. Second-Story Walkways When the Circle Campus opened in 1965, a broad second-story walkway ran from the north side of Harrison Street all the way to Lecture Center A, where it joined the Great Court above Circle Forum. Beyond the Forum, it continued south to Science and Engineering South. This was the north-south spine of the campus. For the first thirty years of our history, students moved around the campus via an extensive system of elevated “pedestrian expressways” linking all 9 the buildings. This was Netsch’s original idea to avoid creating an Walkwaysuninterrupted expanse of concrete in the tightly bounded area of the campus. Second-story walkwaysConcrete and slabs of granite, ten by twenty feet and a foot thick, were used in their construction. Down the center of large sections of the walkways Netsch left an opening through which shrubs and trees could grow up, softening the overall effect. Besides transporting people above, the walkways sheltered pedestrians below among “urban trees,” as Netsch referred to the columns supporting them. Today only photographs of the north-south walkways remain; a wide sidewalk traces the route. Fate of the Walkways Over a six-year period ending in 1999 the walkways were removed to create a greener, more welcoming campus environment. Circle Forum and the Great Court were dismantled at the same time. This was a highly controversial project which resulted in the elimination of significant elements of the Netsch design. As with Circle Forum and the Great Court, maintenance of the walkways was difficult, especially in winter, when snow had to be removed from exposed surfaces and the stairways leading up to them. Netsch had designed the steps with heating Demolitionelements to melt the snow, but the transformers failed and were never replaced. Salt, in conjunction with the annual freeze and thaw cycles, gradually caused the concrete stairways to crack and deteriorate, seriously limiting access and use. Granite damaged during demolition was donated to the city of Chicago, which used it to build an artificial reef at 57th Street and Lake Shore Drive. Today 37 percent of the campus is devoted to green space, which includes more than 5,000 deciduous and evergreen trees. Henry and Jefferson Halls Trustees of the University of Illinois selected the names for the classroom buildings on the Circle campus. Henry and Jefferson Halls were named for Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson, both governors of the Commonwealth of Virginia when Illinois was a part of that territory. Dating from the first two phases of campus construction, the linked classroom buildings feature common design elements that contribute a signature appearance to the Netsch campus. Exterior reinforced concrete pillars frame and support the three-story buildings, which feature recessed window walls adjoining open galleries on the top two floors. University Hall and Science and Engineering Offices incorporate similar design elements. 10 Block I Window Design The upper two floors of the classroom buildings feature long narrow windows in the form of a block I for Illinois, a signature of the Netsch design at UIC. The shape of the recessed windows limits the amount of light that can enter the building, thus eliminating the need for blinds, curtains, or other window treatments in the building interior. The long rectangular central sections feature bronze glass, a relatively new material at the time, to control light and heat in summer. The trapezoidal top and bottom sections have clear glass. Connecting Walkways Enclosed walkways linked the closely adjoining classroom buildings of the historic Netsch campus so that students traveling from one building to another need not go outside. Here the original walkway, no longer in use, has been replaced by a two-story glass-enclosed accessible passageway linking the two buildings. The broader walkway, and an elevator, are recent additions to address requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act. University Hall The 28-story office tower is the tallest structure on campus and the most visible symbol of Netsch’s revolutionary campus design. Intended as a campus landmark, its monumental silhouette stands tall on the Near West Side of Chicago. The building’s exposed reinforced concrete skeleton and narrow recessed windows match the classroom buildings scattered throughout the campus. “Big Shoulders” Design Borrowing from Carl Sandburg’s evocation of Chicago as the “City of the Big Shoulders,” Walter Netsch designed “big shoulders” into his most prominent campus structure. Viewed from the east and west sides, University Hall expands as it rises, measuring 150 feet wide up to floor eight, 160 feet wide from floor 9 to 16, and 170 feet wide from floor 17 to 28. A series of cantilevers makes this unusual design possible. Seen from the north and south ends, the building width remains constant. Enormous columns at ground level support the weight of University Hall. 11 Rebecca Port Faculty-Student Center The Rebecca Port Faculty-Student Center occupies the first and second floors in the southwest corner of University Hall. A generous gift from campus benefactor Sid Port funded the recent renovation of this part of the building, and the Port Center opened in spring 2004. The original walkways that connected University Hall to other campus buildings passed through the second floor area, where a huge granite sign bears the name University Hall. A seating area at the west end occupies the stub of a walkway that once carried pedestrians down to ground level via a pair of circular ramps mimicking the nearby expressway interchange. The principal points of entry from the walkways were at the second floor level in all the Netsch buildings. Even today, these areas are generally more finished and more attractive than the floor below. Behavioral Sciences Building The four-story geometric structure on the far side of University Hall Plaza is the Behavioral Sciences Building. Dating from the third phase of campus construction, BSB combines concrete and brick in what Walter Netsch considered his most sophisticated example of Field Theory design at UIC. The geometric complexity of the building renders the interior extremely difficult to navigate. Only in recent years has extensive signage been added to aid those searching for a particular classroom or office. Stevenson Hall Stevenson Hall is named for Adlai E. Stevenson I, a Congressman from Illinois and the twenty-third Vice President of the United States. The two classroom buildings that were to form a cluster with Stevenson Hall were never built. 12 Lincoln, Douglas, and Grant Halls Lincoln and Douglas Halls are named for Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, two great political leaders from Illinois. Grant Hall bears the name of Civil War General and U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant. Like the other Netsch classroom buildings, these three are connected by enclosed walkways. Today the original Netsch walkway still links Douglas to Lincoln, while a more recent two-story glass-enclosed walkway links Douglas to Grant. An original granite bench stands to the left of the entrance to Grant Hall. Housing the Sandi Port Errant Language and Culture Learning Center, Grant Hall illustrates a striking and important transition to green architecture at UIC. Here Lincoln, Douglas, and Grant are in the foreground, showing their proximity to the Forum. This is just before demolition. Green Architecture at UIC While Douglas Hall looks much as it did when the campus opened in 1965, Grant Hall has changed dramatically, thanks in part to a generous gift from UIC benefactor Sid Port in memory of his daughter. Today Grant Hall houses the Sandi Port Errant Language and Culture Learning Center, a state-of-the-art learning environment created by the Smithgroup. A remodel of Lincoln Hall will soon follow. The new Grant Hall is a model of energy efficiency. Fourteen 500’ deep geothermal wells located nearby help to heat and cool the building naturally, making this the first campus classroom building that maintains a comfortable temperature year-round. Given an opportunity to influence the redesign of Grant Hall, UIC faculty and students asked for improved heating and cooling. A grant from the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation made this cost-efficient, environmentally friendly geothermal system possible. More natural light was another suggestion from faculty and students. To achieve this, the new façade is composed mostly of energy efficient glass. Gone are the narrow recessed windows, Netsch’s solution for eliminating blinds or curtains in the building interior. Recognizing the importance of the building’s original modernist esthetic, the Smithgroup matched the window rhythm to that of the adjoining buildings. Richard J. Daley Library Dating from 1963, the library is named for former Mayor Richard J. Daley, who was instrumental in bringing a campus of the University of Illinois to the city of Chicago. Considered an anchor building of the historic Netsch campus, the fourstory library was built in two stages: first, the central structure, followed by additions on the north and south ends. The original building extended to 13 the end of the first brick-faced bays. Two additional bays were eventually added at each end. Two wings running to the west were planned but never built. Stucco panels visible along the west face of the building indicate their intended placement. Science and Engineering Offices Science and Engineering Offices, 13 stories in height, opened for use in 1968, when Morgan Street was the westernmost campus boundary. The two sections of the building, slightly off-set from one another, contain matching concrete-framed scissor staircases, visible from the building exterior. Again, narrow recessed windows on the building signal the work of Walter Netsch. A large engraved block of granite bearing the name Science and Engineering Offices identifies the building on both the north and south sides. Today a black wrought iron fence has replaced the brick wall that surrounded the historic Netsch campus. Taft, Burnham, and Addams Halls Each building in the Taft-Burnham-Addams cluster was named for an individual who seized Chicago as a place of opportunity. Loredo Taft was a sculptor, educator, and cultural leader. Architect Daniel H. Burnham, known to have said, “Make no little plans,” coordinated the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Nobel Peace Prize winner Jane Addams founded Hull-House, the first settlement house in Chicago, in 1889. These three classroom buildings are linked by the original Netsch-designed walkways. An original granite bench still stands to the left of the entrance to Addams Hall. 14 Science and Engineering Laboratories Walter Netsch described the enormous Science and Engineering Laboratories as “a city underneath a roof.” Here the architect used bricks twice as large as those used in smaller campus buildings to express the size and strength of structures devoted to science and engineering. They are arranged to form an endless pattern of letter I’s on the building exterior. The dramatic ceiling arch between the east and west sides of these SEL second-story walkway, columnsenormous buildings owes its height to the second-story walkway that has been removed. From under the arch, one can see a concrete walkway still in use at the fourth floor level. The columns supporting the roof here are a much larger version of those surrounding the lecture centers, again proportional in size to the load they carry. They lack the butterfly capitals visible in the other location, and because they have been rotated by 45 degrees, they expose a different geometry. The twisted columns here and on the lecture centers are precursors to the SEL twisted columns twisted geometry of Field Theory. Science and Engineering South Science and Engineering South, created by Netsch in phase three of campus construction, is another example of his Field Theory design model, which consisted of rotating simple squares by 45 degrees to form complex geometric elements radiating outward. The two major wings of the building contain offices and laboratories to the east and classrooms to the west. A planned phase four addition was cancelled. The covered breezeway area and staircases leading away from it utilize granite as the building material. Blue Island Corridor Blue Island Avenue, one of the diagonal streets intersecting the grid system on the south side of Chicago, originally ran north as far as Halsted Street. With the construction of the Chicago Circle campus, Blue Island Avenue from Roosevelt Road to Halsted Street was removed. Although the diagonal thoroughfare across campus is gone, it still traces a faint line from the corner of Taylor and Morgan to the corner of Harrison and Halsted. Underneath the Blue Island corridor runs one of Commonwealth Edison’s main arteries for 15 power to the Loop. Because of the power lines, Walter Netsch was unable to build any structures over this underground corridor. The garden south of Science and Engineering Offices owes its existence to this building restriction. Netsch-designed Fence To the east of the Taylor and Morgan intersection, one of the remaining Netsch-designed fences borders parking lot 10. Divided horizontally into three sections, the fence features vertical members spaced further and further apart as it rises. This style of fence also runs south along Halsted from Hull-House to the intersection with Taylor. Chicago Circle Memorial Grove Walter Netsch designed this garden with its elliptical asphalt path and low granite benches in 1968. Originally enclosed by brick walls, Chicago Circle Memorial Grove is now surrounded by a wrought iron fence. The striking scissor staircase of Science and Engineering Offices is visible from the garden. In the lawn near SEO is a small octagonal plaque dating from 1973. It commemorates a member of the Physical Plant staff: Harry W. Pearce, Associate Director Emeritus, Physical Plant, Coordinator of Phase 1 Construction at Chicago Circle Memorial Grove. 16 Addenda Chronology of Campus Construction Phase One – 1963 to 1965 When the university opened in 1965, only Phase One buildings were ready. They consisted of University Hall, the lecture centers, the original library, the north section of Science and Engineering Labs, and the following classroom buildings: Jefferson, Grant, Douglas, Lincoln, Burnham, Addams, and Taft. Architects working under Netsch included C.F. Murphy, who designed the two student unions. Chicago Circle Center, known today as Student Center East, and Chicago Illini Union, or Student Center West, were both built during the first phase of campus construction. Phase Two – 1966 to 1968 Buildings added in Phase Two were the north and south additions to the library, the south section of Science and Engineering Labs, Science and Engineering Offices, Architecture and Art, and Henry and Stevenson Halls. All were designed by Walter Netsch. Phase Three – 1967 to 1971 The Behavioral Science Building and Science and Engineering South, both designed by Walter Netsch, were constructed between 1967 and 1969. Architect Harry Weese designed the Physical Education Building, the UIC Theater, and the Education, Performing Arts, and Social Work building, which were erected between 1968 and 1971. The following projects scheduled for Phase Three were cancelled: Architecture and Art addition, west wing additions to the library, and two classroom buildings which were to form a cluster with Stevenson Hall. Phase Four – 1970 All Phase Four buildings were cancelled: Netsch’s addition to Science and Engineering South and Harry Weese’s Performing Arts and Classroom/Office Building. For More Information Interviews with Walter Netsch, August 4 and 11, 1998, UIC Oral History Project, Office of the UIC Historian Oral History of Walter Netsch, Interviewed by Betty J. Blum, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Architects Oral History Project. Some Fields Are in the City, A Talk for the Chicago Literary Club, William G. Jones, March 28, 2005 Accompanying PowerPoint slides A Tribute to Walter Netsch: Campus Designer and Architect of the University of Illinois at Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Architecture and the Arts Commencement Video, May 10, 2008 The University of Illinois at Chicago: A Pictorial History, Fred W. Beuttler, Melvin G. Holli, and Robert V. Remini, The College History Series, Arcadia Publishing, 2000 Walking About UIC: Reading Urban Texts, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, 1999 Walter A. Netsch, FAIA: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook, Northwestern University Library, 2008 17 Acknowledgements Discover UIC wishes to acknowledge everyone who has shown interest in and support for this project. We extend our apologies to anyone who has been left off. Beuttler, Fred, Office of the UIC Historian Bruegmann, Robert, Department of Art History Chapman, Warren, Office of the Vice Chancellor for External Affairs Cook, James, Facility Information Management Ebel, Darlene, Facility Information Management Gislason, Eric, Office of the Chancellor Gislason, Sharon Fetzer, Department of Chemistry Haar, Sharon, Department of Art History Hale, Debra, Web Communications, Enrollment and Academic Services Hendry, Julia, University Library Jones, William G., University Library Kaufman, Lon, Undergraduate Affairs and the Honors College Kirshner, Judith, College of Architecture and the Arts Knutson, Donna, Office of the Chancellor Naru, Linda, University Library Norsym, Arlene, Alumni Association Okimoto, Kurt, Web Communications, Enrollment and Academic Services Planas, Fernando, Admissions and Records Remini, Robert, Office of the UIC Historian Rouzer, Rob, UIC Student Centers Snow, Carole, Enrollment and Academic Services Sokol, David, Department of Art History Stempel, Laura, Faculty Affairs Susinka, William, Office of the Provost Tam, Mo-Yin, Faculty Affairs Tynan, Kevin, Marketing Communications Vatuk, Sylvia, Department of Anthropology Waak, Jason Marcus, Office of the UIC Historian Wagoner, Wendy, Office of Campus Learning Environments Weller, Ann, University Library Zweigle Yee, Liz, Marketing Communications 18 Photo Credits Photos and images courtesy of: Office of the UIC Historian Office of Facility Information Management University Library Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill Walter Netsch Orlando Cabanban, Photographer Chicago Sun-Times UIUC William G. Jones Robert M. Rouzer Eileen Tanner 19