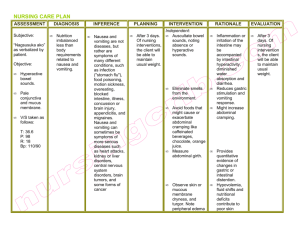

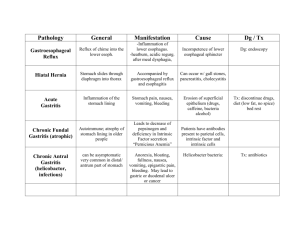

Care of the Patient with a Gastrointestinal Disorder

advertisement