Resisting La Migra

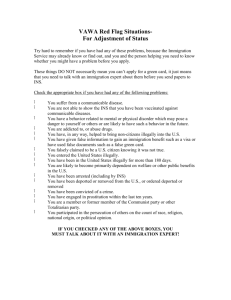

advertisement