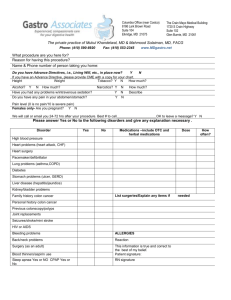

large intestine - College of Veterinary Medicine

advertisement