From Paternalism to Imperialism: The U.S. and the Boxer Rebellion

advertisement

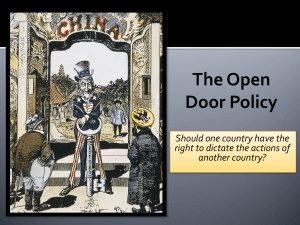

LYDIA R. NUSSBAUM LYDIA R. NUSSBAUM From Paternalism to Imperialism: The U.S. and the Boxer Rebellion In the second half of the nineteenth century, the United States changed the focus of its foreign policy from landed expansion to commercial expansion. This change was the result of an increasingly efficient American industrial complex that began to produce more goods than could be sold. To avoid the domestic discontent that accompanied this excess of goods and lack of circulating capital, the United States looked for more foreign markets in which to sell its products. The two main areas of interest were Latin America and China, yet the attitude of the United States towards these two regions was markedly different. Because of their proximity to Latin America and the Monroe Doctrine, Americans considered themselves entitled to Latin American markets and approached them in an imperialist manner. But with respect to China, the United States distanced itself from the imperial foreign powers and instead presented itself as a protective ally. It is because of this unique relationship with China that the United States found itself in a political quandary at the turn of the century. With the outbreak of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the United States was forced to choose between its role as a paternal protector and its role as a blossoming imperial power. The Boxer Rebellion and the ensuing American intervention marked a turning point in United States-Chinese relations whose repercussions would last well into the next century. Prior to 1898, the United States did not see itself as a colonizing, imperialist power. It prided itself on remaining aloof and uninvolved in wars fought by other foreign nations to acquire new trading rights in China. But ironically, the United States had no qualms about enjoying the benefits of these wars with China.1 In 1844 the United States signed the Treaty of Wangxia with China as fallout from the Opium Wars fought between the Chinese and the British. The Treaty of Wangxia gave the United States most-favored-nation status, which allowed the United States the same trade rights with China as any other nation, as well as extraterritorial rights to protect United States’ citizens and 1 DISCOVERIES property in China.2 A little more than a decade later, when Great Britain and France declared war on China in 1857, the United States again avoided involvement but did not hesitate to help itself to a share of the new trade opportunities, the “spoils won by the Europeans,” by signing the Treaty of Tianjin in 1858.3 Without having to lift a finger, the United States took full advantage of the exploitation of China by imperial powers while still maintaining its reputation as an anti-imperialist nation. For the rest of the nineteenth century, international interest in China’s markets grew and foreign powers jostled to gain a competitive edge there. The United States continued its role as China’s anti-colonial protector against European and Japanese colonization because without a stable Chinese government, the United States’ most-favorednation status meant nothing. If areas of China fell under control of other foreign powers, American traders would not have unlimited access to ports. Instead they would be charged new and higher tariffs imposed by the colonizing nation. This open trade relationship with China was termed the “Open Door,” and the United States had good reason to fear for its own safety. In 1897, Germany obtained control of the port of Kiaochow, which handled lucrative trade from Manchuria. Fearing that Germany had gained an advantage, other foreign powers like Japan, Russia, France, and Great Britain pressed for their own individual economic control over other key parts of China.4 Japan claimed Fukien, Russia took Port Arthur in northern Manchuria, France occupied regions of Yunnan and Kwangsi at the border of China and Indochina, and Great Britain snatched more lands around Hong Kong in the Yangtze valley and opened a naval base on the Shantung peninsula.5 This imperial partitioning of China endangered U.S. access to all of China by threatening to close the Open Door. The United States refused to join the scramble for territory. Instead Washington continued to play the role of China’s economic ally and protector against colonization. In 1899, in response to the looming threat other foreign powers posed to American trade agreements with China, Secretary of State John Hay wrote the first “Open Door Note.” He declared, “the Government of the United States . . . cannot conceal its apprehension that under existing conditions there is a possibility, even a probability, of complications arising between the treaty powers which may imperil the rights insured to the United States under our treaties with China.”6 Hay stressed the importance of maintaining the Open Door policy to ensure equal trade for all nations 2 LYDIA R. NUSSBAUM in the China market and expressed his “sincere desire that the interests of [American] citizens may not be prejudiced through exclusive treatment by any of the controlling powers within their so-called ‘spheres of interest.’”7 The Open Door Note was as much a message to the other foreign powers as it was a message to China. The United States needed to convince China that it was not like the other foreign nations, but instead had friendly intentions and no desire to rob China of her sovereign powers. Hay asserted that “no matter to what nationality [a port] may belong . . . duties so leviable shall be collected by the Chinese government.”8 Thus, although foreign nations could control Chinese ports, the Open Door policy required that the ports’ customs receipts go to the Chinese government rather than to an imperial power. This facet of the first Open Door Note indicated the U.S. support of China’s territorial and economic sovereignty. However reluctantly the other powers received Hay’s pronouncement, they agreed upon the principle of free trade and recognized Chinese control over its trade. It seemed the only way to keep one nation from receiving special privileges that could be used to exclude commercial rivals. Thus, Hay thought the threat of a fractured China had dissipated with the publication of the Open Door Note in 1899. But Hay soon discovered that the China problem had not been solved. In spite of the U.S. attempts to protect Chinese sovereignty from growing foreign spheres of interest—and also safeguard American interests—China remained unstable. In October of 1899, following a poor harvest in the provinces of Chihli and Shantung, a secret society called “Boxers” rallied together “with the avowed purpose of driving out foreigners and of extirpating Christians.”9 The Boxers practiced the art of boxing and quarterstaff—a kind of martial arts using iron-tipped poles. Some followers added their own occult practices and formed the secret society of “The Fist of Righteous Harmony.” As the viceroy of Chihli observed, these people believed that “spirits from on high [would] descend and aid and protect their bodies, so that they [could] withstand the fire of guns or cannon.”10 The two groups melded, and their antiforeign movement spread with great rapidity throughout China in a violent reaction to the growing presence and subsequent power of foreigners. The Boxers and their followers destroyed churches, burned Christian converts, and attacked foreigners while sounding the “cry of ‘Down with Christianity.’”11 They even assassinated Baron von Ketteler, the German foreign Minister to China. But the rebels were not just 3 DISCOVERIES riotous mobs of common people: the movement received support from all sectors of Chinese society, including the Empress Dowager and her imperial counselors. Foreigners as well as some Chinese feared that because of the great number of rebel sympathizers in positions of power, the Chinese government would fail to suppress the anarchist movement and that the chaos in China would spin out of control.12 As one foreign bishop wrote the French minister, “Upon the east of us pillage and incendiarism are imminent; we are hourly receiving the most alarming news. Peking is surrounded on all sides; the ‘Boxers’ are daily coming nearer the capital, delayed only by the destruction which they are making of Christians.”13 Americans, too, fell victim to the Boxer’s anti-foreign attacks. Many foreign missionaries in China were American and just as susceptible to the anti-Christian violence of the Boxer movement as were the other foreigners in China. Therefore, despite U.S. efforts to stand apart from the other foreign imperial powers as an anti-imperialist, paternal ally, the Chinese people did not see a difference—Christians were Christians no matter what nationality. It is also possible that prior to the Boxer Rebellion, some Chinese doubted the good intentions of the United States and believed they had imperial designs in spite of Hay’s first Open Door Note. In the same year Hay produced the first Open Door Note, the United States annexed all of the Philippine Islands with a great deal of bloodshed; thus, it seems likely that many Chinese would have had serious reservations concerning U.S. intentions in China after witnessing its aggressive, imperial conduct. Although the United States tried to portray itself as China’s ally against other foreign nations, Americans were included as targets of the Boxers’ anti-foreign attacks, proving that not all of China was convinced by Washington’s protective role. The Boxer Rebellion placed U.S. policymakers in an awkward position because it forced them to decide if the United States was a paternal protector or a blossoming imperial power. This decision hinged upon whether or not the United States should send troops to put down the rebellion in China, thereby restoring order and protecting American citizens and economic interests. The United States had no military presence in China because it had distanced itself from the other imperial powers and operated as a friendly trading partner. Indeed, deployment of troops raised serious questions. If the United States chose not to send troops, then the anti-foreign rebellion would escalate, 4 LYDIA R. NUSSBAUM more Americans would die, and the future of China would become even more uncertain. Clearly, the United States could not risk a chaotic China. But opting for military force also had its consequences. First, American interference in Chinese domestic affairs with an armed force would disregard Chinese sovereignty and violate the supposed partnership between the two countries. Second, if the United States established a military presence in China, other foreign nations would have an excuse for sending in their own troops to protect their “spheres of interest,” and China would be carved up between five colonial powers, shutting the Open Door forever. Washington faced the dilemma of whether to preserve its economic interests and the Open Door, or whether to maintain its image as anti-imperialist protector of Chinese sovereignty. But the American decision-making process involved factors other than threats to U.S. economic interests and the endangerment of American citizens in China. The United States considered itself the model Republic, an agent of liberty to the rest of the world.14 Just as Christian missionaries believed it their duty to preach the word of God to “heathens,” Americans took it upon themselves to encourage and spread their republican ideology across the globe. President William McKinley captured this American mentality in his annual message to Congress in 1900: American liberty is more firmly established than ever before, and that love for it and the determination to preserve it are more universal . . . . Popular government has demonstrated in its one hundred and twenty-four years of trial here its stability and security, and its efficiency as the best instrument of national development and the best safeguard to human rights.15 Americans have always justified their foreign policy with this political dogma of superiority and altruism, and the turn of the century was no exception. Ironically, for all of the United States’ desire to spread liberty and republican progress throughout the world, they hated revolutions! Since at least the French Revolution in 1789, Americans showed an aversion to civil disorder and chaos, and feared the prospect of social upheaval: a violent and radical lower class taking away and redistributing private property formerly held by a wealthy class. Expressing one of its central, underlying themes, the United States’ own Declaration of Independence equates freedom with the individual’s right to own property. Thus, the confiscation of property and possessions that accompanies social upheaval was seen as a violation of the human right to freedom.16 5 DISCOVERIES The Boxer Rebellion threatened these tenets of American ideology, freedom, and the right to property. As part of its philanthropic mission, the United States believed that by standing apart from the other foreign powers and adopting an anti-imperialist role, it could influence China to westernize. In the first Open Door Note, the United States argued against colonialism and instead favored “administrative reforms so urgently needed for strengthening the Imperial government and maintaining the integrity of China in which the whole Western world is alike concerned.”17 But the Boxer Rebellion sent the clear message that many in the Chinese population had no interest in American tutelage. The Boxers endangered American influence, and consequently interfered with the U.S. mission to spread liberty throughout the world. Also, Washington feared the Boxer uprising could become another French Revolution. The Boxer Rebellion had all the right ingredients: it involved a violent, radical faction that threatened individual freedom of an elite by destroying property. Moreover, in the case of the Boxer Rebellion, that elite group was the foreigners, to which the Americans belonged. The situation reached a climax when the Boxers laid siege to the foreign legations in Peking, trapping Americans, British, Chinese, and others. It was this “condition . . . of virtual anarchy” in Peking that forced the Americans’ hand—in the spring of 1900, President William McKinley sent five thousand United States marines to put down the Boxer Rebellion. Hay produced an explanatory second Open Door Note, in which he firmly defended the United States’ reasons for using military force in China.18 He stressed that the primary purpose of sending in force was “rescuing the American officials, missionaries, and other Americans who [were] in danger” and “to seek a solution which may bring about permanent safety and peace to China . . . and safeguard for the world the principle of equal and impartial trade with all parts of the Chinese Empire.”19 In addition, the United States made sure that other foreign powers who also sent troops to aid in suppressing the Boxers would remove them as soon as the danger ended to ensure that “the treaty rights of all the Powers will be secured for the future, the open door assured, [and] the interests and property of foreign citizens conserved.”20 That decision to use military force to stop the Boxer Rebellion had serious ramifications that reverberated throughout the twentieth century. Hay’s and McKinley’s decision to send troops to China 6 LYDIA R. NUSSBAUM vitiated all of their previous efforts to maintain some semblance of Chinese autonomy. The Open Door policy’s hands-off approach to China had ended. Even more important, the U.S. failed to distinguish itself from the other imperial powers itching to carve up China. Many Chinese lost faith in the good intentions of Americans, and the explosion of anti-foreign sentiment manifested in the Boxer Rebellion only continued to fester. That resentment increased when Americans joined the other imperial powers in the drafting of the 1901 Boxer Protocol— a humiliating punishment that demanded significant monetary compensation, the stationing of foreign troops in the capital, and the denial of China’s economic autonomy. In the years following the Boxer Rebellion, the United States continued to press for free trade with China. But China now proved much less willing to comply. The blatant racial discrimination of the United States government against Chinese through the continued use of Chinese Exclusion Acts only served to confirm China’s mistrust of the United States. China made movements of open retaliation such as boycotting American goods in 1905 in an attempt to assert itself economically. But too many foreign powers had designs on China, and China had neither the unity nor the strength to oppose them all. Japan and Russia wrestled for control of Manchuria, and the United States pressed Beijing for the rights to build railroads all over China. In 1911, internal agitation developed into a revolution against a weakened Imperial government that continued to tolerate foreign meddling. The revolution only threw China into deeper chaos: the country was wracked by uprisings and civil wars, which ultimately culminated in the Communist Revolution of 1949. In hindsight, had the United States chosen not to interfere with the Boxer Rebellion, the history of the relationship between Americans and Chinese may have run a different course. But because of economic interests and its own political dogma, the United States did intervene with military force. As a result, the United States abandoned its role as China’s anti-colonial protector and instead took its place among the ranks of the other imperial powers. Ultimately, this decision marked the beginning of the redefinition of U.S.-Chinese relations in the twentieth century. ❖❖❖ 7 DISCOVERIES Works Cited “The Boxer Protocol.” Peking. 7 Sept. 1901. <http://web.jjay.cuny.edu/ ~jobrien/reference/ob26.html>. “Ch’ing China: The Boxer Rebellion.” 1996. <http://www.wsu.edu: 8080/~dee/CHING/BOXER.HTM>. Davids, Jules, ed. American Diplomatic and Public Papers: The United States and China, vol. 5, doc. #17: letter from Bishop Favier to French Minister. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1981. Hay, John. “The First Open Door Note, 1899.” Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, Vol. I: To 1920, ed. Dennis Merrill and Thomas G. Paterson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000. ___. “The Second Open Door Note, 1900.” Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, Vol. I: To 1920, ed. Dennis Merrill and Thomas G. Paterson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000. Hunt, Michael H. Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy. New Haven: Yale UP, 1987. ___. The Making of a Special Relationship: The United States and China to 1914, ed. Dennis Merrill and Thomas G. Paterson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000. Isaacs, Harold. “The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution.” 1938. Chapter 1. <http://www.zhongguo.org/Isaacs/chapter1.htm>. LaFeber, Walter. The American Age: U.S. Foreign Policy at Home and Abroad, Vol. 1. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1994. Notes 1 Walter LaFeber, The American Age: U.S. Foreign Policy at Home and Abroad, Vol. 1. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1994. 103. 2 LaFeber 103. 3 LaFeber 103. 4 LaFeber 200. 5 Michael H. Hunt, The Making of a Special Relationship: The United States and China to 1914, ed. Dennis Merrill and Thomas G. Paterson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. 2000. 431. 6 John Hay, “The First Open Door Note, 1899,” Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, Vol. I: To 1920, ed. Dennis Merrill and Thomas G. Paterson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000. 423. 7 Hay 423. 8 LYDIA 8 R. NUSSBAUM Hay 424. Jules Davids, ed., American Diplomatic and Public Papers: The United States and China, vol. 5, doc. #9: letter from Conger to Hay. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1981. 32. 10 Jules Davids, ed., American Diplomatic and Public Papers: The United States and China, vol. 5, doc. #12: Proclamation by the viceroy of Chihli. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1981. 34. 11 Jules Davids, ed., American Diplomatic and Public Papers: The United States and China, vol. 5, doc. #59: Memorandum given by the Chinese Minister. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1981. 122. 12 Davids 122. 13 Jules Davids, ed., American Diplomatic and Public Papers: The United States and China, vol. 5, doc. #17: letter from Bishop Favier to French Minister. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1981. 43–44. 14 Michael H. Hunt, Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy. New Haven: Yale UP, 1987. 104. 15 Jules Davids, ed., American Diplomatic and Public Papers: The United States and China, vol. 5, doc. #147: President McKinley’s address to Congress. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1981. 336. 16 Hunt, Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy. 117. 17 Hay, “The First Open Door Note, 1899.” 423. 18 John Hay, “The Second Open Door Note, 1900.” Major Problems in American Foreign Relations, Vol. I: To 1920, ed. Dennis Merrill and Thomas G. Paterson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000. 425. 19 Hay 426. 20 Jules Davids, ed., American Diplomatic and Public Papers: The United States and China, vol. 5, doc. #100: Telegram from Adee to Herbert H. D. Peirce, St. Petersburg. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1981. 190. 9 9