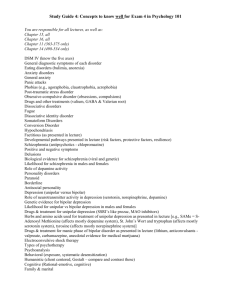

Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder

advertisement