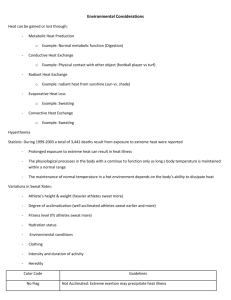

Exertional Heat Illnesses in Athletics

advertisement

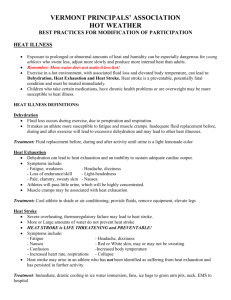

Exertional Heat Illnesses in Athletics Did you know… 11 From 2001-2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that 75% of patients treated for heat illnesses in emergency departments were males; 35% were between the ages 15 and 19.1 On average, 6,000 people per year seek emergency medical care for heat related illnesses suffered while participating in outdoor recreational activities.2 In the athletic population, exertional heat stroke (EHS) is the third leading cause of death among athletes3 and first during the summer months.4 Heat illnesses are an inherent to physical activity and increase with rising ambient temperature, relative humidity and poor planning and preparation. Without prompt and appropriate medical care; patients suffering from EHS are at risk for organ failure, brain damage, or death.1 What is exertional heat illness? Exertional heat illnesses (EHI) occur when the body’s temperature control system becomes overwhelmed and body fluid is lost through dehydration or sweating. This results in the inability to cope with excess heat produced during activity.3-6 The evaporation of sweat from the skin is the most efficient means of losing this heat; however, during hot and humid weather sweating may not be enough to dissipate the buildup of excess body heat.3-4 Failure to regulate an elevated body temperature increases the risk of multi-system organ failure, brain damage, cardiac arrhythmias, and death.3-4, 7-9 Are there different types of exertional heat illness? 11 Exertional heat stroke is a medical emergency and requires immediate rapid cooling and activation of EMS! There are 3 main types of EHI: (1) exercise-associated muscle (heat) cramps, (2) exercise (heat) exhaustion, and (3) exertional heat stroke. Two other heat related illnesses that should not be overlooked are heat syncope and exertional hyponatremia. How do I know if I am suffering from an exertional heat illness? To properly manage EHI requires being able to define and identify each condition's characteristics: • Exercise-associated muscle (heat) cramps: acute, painful, involuntary muscle contractions that present during or after intense exercise.5,6 Possible causes include: (1) excessive sweating, (2) dehydration, (3) electrolyte imbalances, (4) muscle fatigue, or (5) a combination of these factors.5 It does not have to be very hot for heat cramps to occur.8 • Exercise (heat) exhaustion: occurs frequently during hot, humid weather and results in the inability to continue exercising due to: (1) excessive sweating, (2) dehydration, (3) electrolyte imbalance, (4) fatigue, or (5) combination of these factors. Other warning signs: cool, clammy, and pale skin, muscle cramps, dizziness, headache, nausea/vomiting, decreased urine output, and increased body-core temperature. If untreated, heat exhaustion can quickly progress to EHS.5 • Exertional heat stroke: a life-threatening condition with an elevated core temperature > 104°F. Body-core temperature can rise to 106°F or higher within 10-15 minutes resulting in complete thermoregulatory system failure.3,5 Neurological changes to the central nervous system are often the first sign of EHS. Warning signs include: (1) increased heart rate, (2) low blood pressure, (3) cessation of sweating (skin may be wet or dry at the time of collapse), (4) increased breathing rate, (5) altered mental status, (6) vomiting, (7) diarrhea, (8) seizures, and (9) other circumstances (i.e., hot and humid environment, intense exercise). The longer the body temperature remains elevated, the greater the likelihood of permanent disability or death if NOT treated rapdily.3,5, 7-10 What should I do now? Immediate and proper care is necessary to treat EHI. • Exercise-associated muscle (heat) cramps: to relieve cramps you must stop activity, stretch the tissue, and massage the muscle. Replace lost fluids with sodium-containing fluids (sports drink). A recumbent position also allows more rapid redistribution of blood flow to cramping leg muscles.5 • *Exercise (heat) exhaustion: body-core temperature measured with a rectal thermometer is the most accurate way to distinguish between exercise exhaustion and EHS. Because this is often not practical, assess cognitive (memory, judgment, and reasoning) function and vital signs. If core temperature is elevated or abnormal: (1) remove to a cool/shaded area, (2) remove excess clothing, (3) start replacing lost fluid, and (4) cool the individual using: fans, ice towels, or ice bags. Contact EMS if recovery is not rapid, uneventful, the person begins vomiting, shows signs of EHS, or loses consciousness.8 • *Exertional heat stroke: begin RAPID body cooling and summon medical personnel.3,5,10 Aggressive cooling is the MOST critical factor in treating EHS.3,5 The fastest way to decrease body-core temperature is to immerse the body in a tub of cold water (≈35°F-59°F). Monitor core temperature during the cooling therapy via a rectal thermometer and remove when the body-core temperature reaches 102°F. When this is not feasible, remove from the tub once cognitive function improves or after 20 minutes to avoid overcooling.10 Monitor vital signs and other signals of EHS.5,10 If immersion is not feasible, other methods can be 3 used to reduce body temperature: (1) remove clothing, (2) wet ice towels rotated and placed over the entire body (3) cold water dousing with or without fanning (4) ice bags to as much of the body as possible, especially the major vessels in the armpit, groin, and neck, (5) provide shade and fan the body with air while waiting for EMS.3,5 How do I prevent exertional heat illnesses? The best method to prevent EHI from occurring is to be PREPARED and know how to manage and reduce risk. Simple strategies include:3,5 Ø Ensure appropriate medical care (eg., certified athletic trainer) is available and personnel are familiar with EHI prevention, recognition, and treatment strategies. Ø Establish policies and procedures for cooling athletes before transport to the hospital with all personnel. Ø Conduct a thorough, physician-supervised, medical screening before the season starts to identify at-risk individuals. Factors include: (1) history of EHI, (2) poorly acclimatized, (3) poor physical fitness, (4) recent illness, (5) obesity, and (6) poor nutrition habits. Ø Adapt activities in the heat gradually over 10-to-14 days and progressively increase workload and duration of work in the heat. Also, incorporate a combination of strenuous interval training and continuous exercise. Ø Maintain proper hydration during the season before, during, and after activity. NEVER withhold water as punishment. Ø Match fluid intake with sweat and urine losses to maintain adequate hydration (see the chart above). Drink sodium-containing fluids to keep urine clear to light yellow to improve hydration. Ø Avoid exercising in hot, humid environmental conditions. Ø Modify protective equipment during periods of high environmental stress. Ø Avoid the ‘‘never give up’’ or ‘‘warrior’’ mentality. Ø Sleep at least 6 to 8 hours each night in a cool environment. Ø Eat a well-balanced diet. *Note: Measuring rectal temperature with a flexible probe thermometer is the MOST accurate method possible in the field to assess body-core temperature. You should NOT rely on the oral, tympanic, or axillary temperature for active individuals because these are inaccurate and ineffective measures of body-core temperature during and after exercise.3,5 References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Hendrick, B. Heat illness sends thousands to ER each year. Web site. http://www.webmd.com/fitness-exercise/news/20110728/heat-illness-sends-thousands-to-er-each-year. Accessed July 12, 2012. Hazards - heat wave. Web site. http://www.disastersrus.org/emtools/heatwave/heatwave.htm. Accessed July 12, 2012. Casa D., et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: preventing sudden death in sports. J Athl Train. 2012:47(1):96-118. Bergeron MF, McKeag DC, Casa DJ, et al. Youth football: heat stress and injury risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(8):1421-1430. Binkley H, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: exertional heat illnesses. J Athl Train. 2002; 37(3), 329-343. MMWR. (2006, July 28). Heat-related deaths --- United States, 1999-2003. Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5529a2.htm. Accessed July 12, 2012. Rav-Acha M, et al. Fatal exertional heat stroke: a case series. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328(2):84-7. Rav-Acha M, et al. Unique persistent neurological sequelae of heat stroke. Mil Med. 2007;172(6):603-6. Dematte JE, et al. Near-fatal heat stroke during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(3):173-81. American Red Cross. Emergency Medical Response. Yardley, PA: Staywell; 2012. Photos courtesy of Microsoft Office Template. Photos courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net Original works by the authors. Developed and funded by the Athletic Training Education Program.