Warranties, Disclaimers, and Limitations JOSEPH G

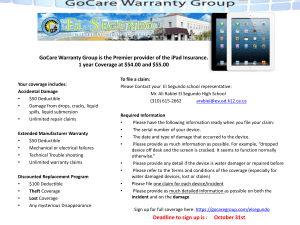

advertisement