Your right to be free from assault by prison guards and other prisoners

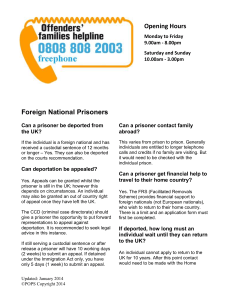

advertisement