Case Discussions - National Osteoporosis Foundation

advertisement

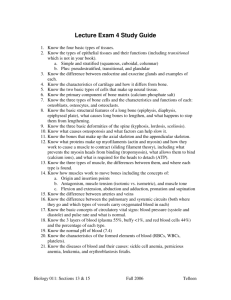

National Osteoporosis Foundation Volume III, Issue 2 OSTEOPOROSIS CLINICAL UPDATES Editorial Boar d OVER-THE-COUNTER PRODUCTS & OSTEOPOROSIS: CASE DISCUSSIONS Angelo Licata, MD, PhD, FACP, FACE Editor-in-Chief Research Director, Metabolic Bone Disease Clinic Cleveland Clinic Foundation Osteoporosis is a complex multifactorial condition affected by a spectrum of biochemical and biomechanical factors. Lawrence G. Raisz, MD Senior Editorial Consultant Professor of Medicine University of Connecticut Health Center Louise Acheson, MD, MS Associate Professor of Family Medicine Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals of Cleveland Richard Bauer, MD Chief of Staff South Texas Veterans Health Care System Carolyn J. Bolognese, RN Clinical Nurse Specialist Bethesda Health Research Peggy Doheny, PhD, RN, ONC Associate Professor, College of Nursing Kent State University Susan L. Greenspan, MD Professor of Medicine University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Anthony B. Hodsman, MD Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology University of Western Ontario Barbara Lukert, MD, FACP Professor of Medicine University of Kansas Medical Center Michael Maricic, MD Chief, Section on Rheumatology Southern Arizona VA Health Care System Paul D. Miller, MD Medical Director, Colorado Center for Bone Research Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center Morris Notelovitz, MD Consultant, Adult Women’s Medicine Gainesville, Florida Karen A. Roberto, PhD Professor & Director, Center for Gerontology Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Carol Sedlak, PhD, RN, ONC Associate Professor, College of Nursing Kent State University Kathy M. Shipp, PhD, PT, MHS Assistant Research Professor Department of Community and Family Health, Division of Physical Therapy Duke University Medical Center Guest Reviewer Bess Dawson-Hughes, MD USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging Tufts University Osteoporosis: Clinical Updates is published by the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF). The views and observations presented in Osteoporosis: Clinical Updates are those of the authors/editors and do not reflect those of the funders or producers of this publication. Readers are urged to consult current prescribing and clinical practice information on any drug, device, or procedure discussed in this publication. There has been much promising research in the field of prevention and treatment. One result of this has been to raise expectations among the public that a wide range of products, from dietary supplements to topical hormone creams, can have a positive impact on bone health. In this issue of Osteoporosis: Clinical Updates, we will look at a variety of over-the-counter preparations promoted for the “treatment” and “prevention” of osteoporosis and review the evidence for their effectiveness. CASE 1: 55-YEAR-OLD WOMAN he first patient we will discuss is a 55-year-old woman who is three years postmenopausal with no history of fracture. T The patient presents for her yearly physical exam. She reports that her 75-year-old mother recently broke a hip after slipping on ice and is worried that she, herself, may be at risk. Given her family history, is this patient at risk for osteo porosis? Yes. History of fragility fracture in a first-degree relative is an established risk factor for osteoporosis. The patient reports that she has been using topical progesterone cream and oral soy supplements for prevention of bone loss. She asks if she should be doing anything else. What are the effectiveness of topical progesterone cream and soy supplements for preventing osteoporosis? There has been very little clinical research on the effectiveness of many over-the-counter (OTC) products on the market that promote themselves as treatments or preventatives for osteoporosis. Neither of the OTC products the patient is using has been shown in clinical trials to prevent osteoporosis or osteoporotic fracture. Isoflavone, a component of soy, has been demonstrated to have a mild estrogenic effect on bone and on the cardiovascular system in women who consume approximately 50 or more mg per day. The patient’s National Osteoporosis Foundation • 1232 22nd Street, N.W. • Washington,DC 20037-1292 • (202) 223-2226 • Copyright © 2002 • All rights reser ved tially harmful effects on bone in patients on long courses of retinoids for skin diseases.1,2 intake of supplements may have a benefit, if her intake is 50 mg or more per day. Clinical trials have shown progesterone creams to have no beneficial effect on bone health. While neither OTC product the patient is using has been proven to help prevent osteoporosis, neither has been shown to cause harm in recommended doses. However, there is solid scientific evidence that adequate calcium and vitamin D intake can slow the rate of bone loss. In addition, recent research suggests that ingestion of supplemental retinol, found in high concentrations in fish oil, can significantly increase a woman’s risk of hip fracture. (RR 1.48 for ≥ 10,000 IU/day). The same increase in risk was not found for intake of vitamin A from beta carotene (see page 4). How can a physician easily estimate if this patient is getting adequate calcium and vitamin D? Should the patient be advised to curtail use of Accutane? Fish oil supplements? The physician can quickly establish if the patient gets adequate calcium by asking how many servings of dairy products she has each day, multiplying this number by 300, adding 250 mg for nondairy dietary calcium sources, and then adding the calcium in any multivitamin or supplement taken. The benefits to the patient of continuing use of Accutane must be weighed against the possible increased risk of osteoporosis. She reports having severe acne without use of the drug. The physician advises that she continue with the Accutane but have a DXA scan now and follow up with DXA every f ive years to measure and monitor her bone density. The physician queries the patient on calcium intake and sun exposure to determine if supplements are needed. After estimating the patient’s daily calcium intake, the physician recommends a daily calcium supplement to bring the patient’s average intake up to 1200 mg/day. Because the patient takes a daily multivitamin that contains vitamin D (400 IU) and participates regularly in outdoor activities, the physician does not recommend additional vitamin D supplementation. The potential cardiovascular benefit of fish oil supplements (for their omega-3 fatty acid content) are most likely offset by their potential harm to the patient’s bones. The physician recommends that the patient discontinue intake of fish oil supplements and that she limit her intake of vitamin A in multivitamins to the beta carotene form. Animal and epidemiological studies have indicated that omega-3 fatty acids from nonretinol sources such as flax seed oil may have a positive impact on bone health (see page 5). CASE 2: 35-YEAR-OLD WOMAN Should the physician discourage continued use of supplemental magnesium, zinc, and soy? The second patient we will discuss is a 35-year-old woman with no family history of osteoporosis. The patient has been taking Accutane (isotretinoin) for 10 years to treat acne. In addition, when the physician takes her medical history, the patient reports that she takes multiple nutritional supplements, including fish oil, flax seed oil, magnesium, zinc, and soy. Not if they are kept within safe tolerable limits: 350 mg/day for magnesium and 40 mg/day for zinc. Because zinc and magnesium are involved in healthy bone metabolism, it is possible that intake of these minerals may be beneficial to bone. However, research is lacking to support this hypothesis. Research on soy, as discussed above, has suggested a mild benefit to bone. Is this patient at increased risk for osteoporosis? The physician recommends a daily calcium supplement. In addition, the physician cautions that there is limited data to support claims of bone health benefits from supplemental flax seed oil, soy, zinc, and magnesium. She may be. Clinical research has demonstrated poten- Estimating Daily Dietary Calcium Intake Product Milk (8 oz) Fortified citrus juice (8 oz) Fortified cereal (no milk), snacks, etc. Fortified cereal with 4 oz milk Yogurt (8 oz) Cheese (1 oz) # of Servings Calcium Content Total calcium (mg) x x 300mg/serving = 300mg/serving = ________________ ________________ x 100mg/serving = ________________ x x x 250mg/serving = 400mg/serving = 200mg/serving = (for nondairy sources) ________________ ________________ ________________ + 250 mg TOTAL CASE 3: 70-YEAR-OLD WOMAN The third patient we will discuss is a house-bound elderly woman, 70 years old, who has low bone hip and spine density on DXA (osteopenia), but not osteoporosis. What dietary issues can the patient address to help maintain her bone health? _____________ ❷ OTC VITAMINS, MINERALS, TRACE ELEMENTS, AND OTHER NUTRIENTS: IMPACT ON BONE HEALTH How to Take Calcium The body can best handle about 500 mg of calcium at any one time, whether from food or supplements. Therefore, calcium-rich foods and/or supplements should be consumed in small doses throughout the day, preferably with a meal. Multiple-tablet doses can easily be split, with the first tablet taken at lunch and the second at dinner. Because the body requires calcium 24 hours a day, some experts suggest consuming a calcium-rich food such as yogurt or a calcium supplement at bedtime to provide a calcium source during the night. The recommended daily allowances, adequate intakes, and tolerable upper limits cited in this newsletter are taken from the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) established by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine, 1997–2001. When insufficient data exist for establishing a recommended daily intake level, adequate intake levels are indicated, representing the median intakes reported from the Food and Drug Administration Total Diet Study. Vitamins, Minerals, and Trace Elements Adequate calcium, vitamin D, and protein intake have all been shown to significantly benefit bone health in elderly women. They alone will not prevent osteoporosis, but they are necessary components of an overall prevention or treatment plan. Calcium. Calcium is essential for blood clotting, nerve function, and countless other metabolic processes. It is also essential for building and maintaining a healthy skeleton. Ninety-nine percent of the body’s calcium reserve is stored in bone. Serum calcium balance is tightly regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcitriol, and calcitonin. Because the body cannot produce calcium, calcium lost through the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and skin must be replaced through the diet. When serum calcium levels are too low, and adequate calcium is not provided by the diet, calcium is taken from bone. Longterm calcium deficiency is a known risk factor for osteoporosis. The recommended daily calcium intake is 1000 for people aged 19 to 50 and 1200 for people older than 50 with a tolerable upper limit of 2500 mg/day. Because of her lack of sun exposure, it is probably safe to assume that this patient is vitamin D deficient. Vitamin D deficiency contributes significantly to bone loss. To establish serum calcium and 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels, the physician runs a blood chemistry. The patient is advised to take a daily supplement that contains adequate vitamin D (400 IU) and calcium (1200 mg). In addition, she is advised to maintain an adequate intake of protein (50 grams/day). Adequate calcium intake is necessary for attaining peak bone mass in early life (until about age 30) and for slowing the rate of bone loss in later life.1 Although calcium alone (or with vitamin D) has not been shown to prevent estrogen-related bone loss, multiple studies have found calcium consumption between 650 and over 1400 mg/day reduces bone loss and increases lumbar spine BMD.2, 3, 4 Are there any other measures that this patient can take to help preserve her bone mass? Immobilization is an established risk factor for bone loss and osteoporosis. The patient is referred to a physical therapist to develop a safe movement/exercise plan to ease the patient into bone-preserving weight-bearing exercises that she may perform at home. The physician discusses drugs approved for osteoporosis prevention and recommends that the patient consider beginning drug therapy to prevent further bone loss. Recommended Calcium Intakes* Ages Birth – 6 months 6 months – 1 year 1–3 4–8 9–13 14–18 19–30 31–50 51–70 70 or older References 1. 2. Okada N, Nomura M, Morimoto S, Ogihara T, Yoshikawa K. Bone mineral density of the lumbar spine in psoriatic patients with long-term etretinate therapy. J Dermatol. 1994;21:308-11. Kindmark A, Rollman O, Mallmin H, Petren-Mallmin M, Ljunghall S, Melhus H. Oral isotretinoin therapy in severe acne induces transient suppression of biochemical markers of bone turnover and calcium homeostasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:266-9. Pregnant & Lactating 14–18 19–50 Amount mg/day 210 270 500 800 1300 1300 1000 1000 1200 1200 1300 1000 *Source: National Academy of Sciences (NAS) ❸ Vitamin D deficiency can be a problem among individuals who avoid sunlight, do not drink vitamin D fortified milk, do not take a multivitamin containing vitamin D, or are homebound or institutionalized, are on dialysis or anticonvulsive medication, or suffer from diabetes, hypertension, chronic neurological disorders, or gastrointestinal diseases. In addition, research on hospital inpatients found a significant degree of vitamin D deficiency (42%) in patients with no known risk factors.5 The adequate intake for ages 50 to 70 is 10 mcg/day (400 IU) and for over age 70 is 15mcg/day (600 IU) with a safe upper limit of 500 mcg/day (2000 IU). Safety of Calcium Supplements The health hazards of exposure to lead are well known. In recent years, much attention has been paid to the fact that calcium carbonate supplements contain trace amounts of lead. In one recent study, 4 of the 7 popular over-the-counter calcium carbonate supplements tested contained lead (~1mg/day for 800 mg/day of calcium and 1-2 mg/day for 1500 mg/day of calcium). 1 Whether or not such levels of exposure are a threat to health is an open question. Calcium is known to offset the effects of lead by blocking its absorption (both in the supplement and in other dietary contributors of lead).2 In fact, research has shown that blood lead levels are lower in people who take calcium supplements than in those who do not.3 As a consequence, Robert P. Heaney, MD, of Creighton University, a leader in the field of calcium and bone, has written, “the calcium sources available today are generally very safe.”2 Vitamin A (retinol). The deleterious effects on bone of high levels of vitamin A (as retinol) are well characterized, including reduced bone mass and increased fracture rates.6 A recent analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study data involving 72,337 postmenopausal women from 1980–98 looked at associations between intake of retinol and hip fracture. The analysis found the risk of hip fracture nearly doubled in women not on hormone-replacement therapy who had retinol intakes of +2000 mcg/day (6700 IU) as compared with intakes under 500 mcg/day (1650 IU).7 Vitamin A from beta carotene was not found to contribute significantly to increased fracture risk.7 The recommended dietary allowance for vitamin A is 900 mcg/day (3000 IU) for men and 700 mcg/day (2300 IU) for women with a limit of 3000 mcg/day (10,000 IU). Liver, fish oil, whole-milk dairy products, eggs, and fortified foods such as margarine are dietary sources of vitamin A. In short, patients are safe taking calcium supplements from respected manufacturers. Patients should, however, avoid supplements derived from dolomite, bone meal, or unrefined oyster shell. Alternatives to calcium carbonate include calcium citrate, calcium phosphate, and (by prescription) calcium acetate. Be advised that calcium carbonate preparations are currently the least expensive and the most widely available. 1. Ross EA, Szabo NJ, Tebbett IR. Lead content of calcium supplements. JAMA. 2000;1425-1429. 2. Heaney RP. Lead in calcium supplements: cause for alarm or celebration? JAMA. 2000;284:1432-33 3. Muldoon SB, Cauley JA, Kuller LH, Scott J, Rohay J. Lifestyle and sociodemographic factors as determinants of blood lead le vels in elderly women. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:599-608. Vitamin C. The recommended intake for vitamin C is 90 mg/day for men over 50 and 75 mg/day for women over 50 with a tolerable upper limit of 2000 mg/day. Higher intake of vitamin C (~100-125 mg/day) has been linked in some studies to reduced hip fracture risk and increases BMD in postmenopausal women. 8, 9, 10 This effect was found to be stronger in women with high calcium intakes.10 Dietary sources of calcium include dairy products (milk, yogurt, and cheeses); fortified juices, breads, and cereals; nuts and seeds; fish eaten with bones (sardines, salmon); soy milk and tofu processed with calcium salts; green vegetables, such as turnip greens, broccoli, and collards; beans, such as chick peas and soy beans; and some fruits, such as oranges, raisins, and dried figs. Research into the effect of vitamin C on BMD is not conclusive, and contrary results have been found. 11 Animal studies suggest that a very high intake of vitamin C (i.e., 2000 mg/day or more) may accelerate bone loss and increase the risk of kidney stones. Achieving bone-building and bone-preserving effects of pharmacologic therapies for osteoporosis requires adequate calcium intake. Dietary sources of vitamin C include citrus fruits and fruit juices; other fruits, such as cantaloupe and strawberries; and some vegetables, such as potatoes, cabbage, peppers, and broccoli. Vitamin D. Vitamin D regulates intestinal calcium absorption and helps mineralize bone. The most readily available source of vitamin D is direct sunlight. However, people are often encouraged to avoid sunlight because of skin cancer and wrinkles, and the skin’s ability to metabolize vitamin D diminishes with age. Other sources of vitamin D include fish liver oils, fatty fish, eggs, liver, and fortified foods such as milk and cereal. Vitamin K. The recommended daily intake of vitamin K is 120 mcg/day for men and 90 mcg/day for women, with no established upper limit. Besides being essential to blood clotting, vitamin K is necessary for making a protein, osteocalcin, involved in bone formation. Vitamin K ❹ is made by bacteria in the intestinal tract and stored in the liver. Food sources of vitamin K include fermented soy and dairy products, fish, meat, liver, eggs, leafy greens, brussel sprouts, cabbage, and plant oils. Patients with malabsorption syndromes or in whom intestinal bacteria have been destroyed by antibiotic therapy should be monitored for vitamin K deficiency. The role of vitamin K supplementation in osteoporosis therapy is as yet unclear. Studies have suggested that vitamin K supplementation over the recommended intake levels may have a positive impact on bone mass in postmenopausal women.12, 13, 14 Research in this area is ongoing. (dark green) vegetables, whole grains, meats, milk, bananas, nuts, and seeds. Because magnesium is found in many foods, magnesium deficiency is uncommon but can be found in patients with malabsorption conditions or those on a limited diet. Magnesium appears to affect bone remodeling, strength, and preservation. However, the small number of welldesigned studies looking at magnesium intake and BMD have to date yielded inconclusive results. Patients with kidney disease should not take magnesium supplements. Boron. There are currently no recommended daily intake or average intake levels established for the trace element boron.16 However, a tolerable upper limit has been established at 20 mg/day.17 Studies in rats have shown increased bone mass with unchanged bone flexibility following exposure to boron. In addition, a study in humans found a positive impact on calcium metabolism in postmenopausal women receiving supplemental boron of 3 mg/day. Common sources of boron are nuts, fruits, milk, eggs, potatoes, vegetables, legumes, and pulses (e.g. peas, beans, lentils). Manganese, Copper, Zinc. The dietary minerals manganese, copper, and zinc are cofactors for enzymes required for healthy bone metabolism. There is currently no recommended daily intake for manganese. Adequate intakes for men are 2.3 mg/day and for women of 1.8 mg/day with a tolerable upper limit of 11 mg/day. Dietary sources of manganese include nuts, legumes, tea, and whole grains. The recommended intake of copper for adults is 900 mcg/day with an upper limit of 10000 mcg/day. Dietary sources of copper include organ meats, seafood, nuts, seeds, cereals, whole grains, and cocoa. Fluoride. Fluoride is a trace element necessary for growth of teeth and bone. There is no recommended daily intake level. Adequate intakes are 4 mg/day for adult men and 3 mg/day for adult women, with a tolerable upper limit of 10 mg/day. Sodium fluoride has long been investigated as a possible defense against bone loss and osteoporosis. High doses (50+ mg/day) have been shown to increase bone mass significantly, but do not reduce risk of fracture, because the bone formed is brittle.18 Research suggests that long-term low doses (~20-50 mg/day) of fluoride with calcium and vitamin D may have benefits for BMD and reduced vertebral fracture risk.19, 20, 21 Since these data are controversial, fluoride is not suggested for the prevention or treatment of osteoporosis. Over-the-counter fluoride preparations containing 1-2 mg were at one time available. Currently, only topical gels and rinses for dental health containing .01%-.1% concentrations are available over-the-counter. Dietary sources of fluoride include marine fish, teas, and fluoridated water. The recommended intake of zinc for adults is 11 mg/day for men and 8 mg/day for women with an upper limit of 40 mg/day, assuming that the person has normal kidney function. Dietary sources of zinc include fortified cereals, eggs, dairy products, nuts, red meat, peas, and certain seafood. Patients with kidney disease should not take zinc supplements. Phosphorus. The recommended intake for phosphorus is 700 mg/day for men and women, with an upper limit of 4000 mg/day until age 70, after which the safe limit drops to 3000 mg/day. Dietary sources of phosphorus include dairy products, meat, peas, eggs, and some cereals. Phosphorous is also found in cola beverages and many processed foods. It has long been known that excess phosphorus intake increases the need for calcium by interfering with calcium absorption. However, a recent study found that phosphorous deficiency may reduce the absorption of calcium and thereby lead to bone loss.15 Strontium. Strontium is a trace element found in sea water. Its primary source in the diet is seafood. Other sources include whole milk, wheat bran, meat, poultry, and root vegetables. There are no recommended daily or adequate intakes established for strontium. However, average daily intakes have been estimated to be about 1 to 3 mg. Research on animals has suggested that strontium may increase bone strength. 22, 23 Human studies have also suggested positive effects of strontium supplementation on BMD.24, 25 However, high intakes of strontium have been found to increase bone fragility and impair vitamin D metabolism and bone mineralization.26 Magnesium. Magnesium is required for many enzyme reactions as well as synthesis of proteins and nucleic acids. Magnesium is needed for the secretion and action of parathyroid hormone, an important regulator of calcium status. The recommended daily intake for men is 420 mg and for women is 320 mg. The safe upper limit for magnesium is established at 350 mg/day from supplement/ pharmaceutical sources (not including food and water), if kidney function is normal. Sources include chlorophyll-containing ❺ Established Bone Benefit • Calcium • Vitamin D • Protein Reading the Label Since 1999, foods and dietary supplements have been required to provide nutritional information on the product’s ingredients. Possible Bone Benefit • Boron • Copper • Fluoride* • Magnesium • Manganese • Omega-3 fatty acids (non-retinol) • Phosphorus • Soy (isoflavones) • Strontium+ • Vitamin C • Vitamin K • Zinc A food’s “Nutrition Facts” panel indicates the amount of calcium in the product in terms of percent daily value (% DV). Dietary supplements usually have a “Supplement Facts” panel that lists nutritional content both in terms of % DV and milligrams or international units (IUs). For the purpose of food/supplement labeling, the % DV for calcium is 1000 milligrams. A food containing 30% DV for calcium contains 300 mg of calcium per serving. Keep in mind that to receive the calcium indicated on the label, one must consume the appropriate size serving. For example, let’s say a product’s Nutrition Facts panel indicates that it contains 1000 mg of calcium “per serving,” and one “serving” is equal to 4 tablets. To receive 1000 mg of calcium, you must take 4 tablets. Consumers who do not read the label carefully may only take 1 tablet, and only get 250 mg of calcium. No Demonstrated Bone Benefit • Progesterone cream Potential Harm to Bone • Vitamin A from retinol • High intake of fluoride • High intake of oxalate • High intake of phosphorous • High intake of strontium * Long-term, low-dose fluoride only + Low-dose strontium only Phytoestrogens and Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Phytoestrogens are compounds found in plants that have mild estrogenic or antiestrogenic effects on specific tissues in the body, depending on factors such as gender, age, and hormonal status. There are two main categories of phytoestrogens: isoflavones and lignans. It’s essential for patients to understand labeling on food and dietary supplements in order to effectively meet their nutritional needs. For more information on nutritional labeling, visit http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/foodlab.html. For more information on calcium, contact the National Osteoporosis Foundation at www.nof.org. An accumulating body of evidence suggests that high consumption of isoflavones (over 50 mg/day) has a beneficial effect on the cardiovascular system and skeleton in postmenopausal women.30,31 Foods and Other Products Dietary sources of isoflavones include soy, chick peas, red clover, and legumes. Long-term clinical trials are needed to assess the effectiveness of isoflavones on fracture rate and BMD at various skeletal sites. Omega-3, or n-3, polyunsaturated fatty acids come from plant sources (lignans) or animal sources (fish oil). Omega-3 fatty acids have been shown in animal and cell research to have a beneficial effect on bone mass.32 In ovariectomized rats, the beneficial effect has been shown to increase with the addition of estrogen.32 To date, human studies have not shown a similar benefit. Plant sources of omega-3 fatty acids (lignans) include soybeans, flaxseed, and walnuts. Animal sources of omega-3 fatty acids include fatty fish (e.g., salmon, mackerel, and sardines). Vegetable sources may be preferable to avoid detrimental effects of retinol, found in high concentrations in fish oil. (See above discussion on vitamin A.) Supplements are widely available. Protein. Recommended intake of protein is 63 grams/day for adult men and 50 grams/day for adult women.27 A highprotein diet has been demonstrated to increase the body’s need for calcium. Furthermore, a high-protein diet can cause urinary loss of calcium. However, a three-year study of 342 men and women over 65 found that in the presence of 500 mg/day calcium and vitamin D supplementation, a high-protein diet (average 79 grams/day) significantly benefited bone density.28 Any association between protein, osteoporosis, and fracture risk has not been fully explored. On the other hand, low intake of protein has been linked to low femoral neck BMD in institutionalized elderly. Outcomes following hip fracture in such patients were significantly improved with protein supplementation, which resulted in reduced bone loss from the hip.29 Oxalate. Oxalate, a nutrient found in some foods, including spinach, rhubarb, and sweet potatoes, binds with calcium, disrupting absorption of the calcium in that food (not in other foods). Oxalate intake is usually not a meaningful problem if daily calcium intake overall is adequate. Progesterone creams. Clinical studies have reported that progesterone applied topically as a cream is absorbed into the body.33, 34 However because absorbed levels of ❻ progesterone observed in studies have been much lower than levels achieved through oral or vaginal progesterone therapies, the bone-health benefits of such therapies are as yet uncertain. One randomized study looking at 102 women found no bone-protective effect at one year of transdermal progesterone therapy (20 mg/day), but did find vasomotor improvement in the treatment group.35 Associated risks to tissues such as the breast have yet to be characterised. It may be advisable to monitor serum levels in patients using progesterone creams. 12.Douglas AS, Robins SP, Hutchinson JD, Porter RW, Stewart A, Reid DM. Carboxylation of osteocalcin in post-menopausal osteoporotic women following vitamin K and D supplementation. Bone. 1995;17(1):15-20. 13.Knapen MH, Hamulyak K, Vermeer C. The effect of vitamin K supplementation on circulating osteocalcin (bone Gla protein) and urinary calcium excretion. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(12):1001-5. 14.Sokoll LJ, Booth SL, O’Brien ME, Davidson KW, Tsaioun KI, Sadowski JA. Changes in serum osteocalcin, plasma phylloquinone, and urinary gamma-carboxyglutamatic acid in response to altered intakes of dietary phylloquinone in human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(3):779-84. 15.Heaney RP, Nordin BEC. Calcium effects on phosphorus absorption: Implications for the prevention and co-therapy of osteoporosis. J Am Coll Nutr.2002; 21(3):239. 16.Chapin RE, Ku WW, Kenney MA, McCoy H, Gladen B, Wine RN, Wilson R, Elwell MR. The effects of dietary boron on bone strength in rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1997;35(2):205-15. 17.Neilsen FH, Hunt CD, Mullen LM, Hunt JR. Effect of dietary boron on mineral, estrogen, and testosterone metabolism in postmenopausal women. FASEB J. 1987;1(5):394-397. 18.Marcus R, Feldman D, Kelsey J, Eds. Osteoporosis. Academic Press, Inc. San Diego, 1996; 1373 pp. 19.Pak CYC, Sakhaee K, Adams-Huet B, Piziak V, Peterson RD, Pointdexter JR. Treatments of postmenopausal osteoporosis with slow release sodium fluoride. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:401-8. 20.Reginster JY, Meurmans L, Zegels B, et al. The effect of sodium monofluorophosphate plus calcium on vertebral fracture rate in post menopausal women with moderate osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(1):1-8. 21.Ringe JD, Kipshoven C, Coster A, Umbach R. Therapy of established post-menopausal osteoporosis with monofluorophosphate plus calci um: Dose-related effects on bone density and fracture rate. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9(2):171-8. 22.Okayama S, Akao M, Nakamura S, Shin Y, Higashikata M, Aoki H. The mechanical properties and solubility of strontium-substituted hydroxyapatite. Biomed Mater Eng. 1991;1(1)11-17. 23.Buehler J, Chappuis P, Saffar JL, Tsouderos Y, Vignery A. Strontium ranelate inhibits bone resorption while maintaining bone formation in alveolar bone in monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Bone. 2001;29(2):176-9. 24.Reginster JY. Miscellaneous and experimental agents. Am J Med Sci. 1997;313(1):33-40. 25.Reginster JY, Roux C, Juspin I, Provvedini DM, Birman P, Tsouderos Y. Strontium ranelate for the prevention of bone loss of early menopause. [Abstract] Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:12. 26.Schaafsma A. de Vries PJ, Saris WHM. Delay of natural bone loss by higher intakes of specific minerals and vitamins. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2001;41(4):225-49. 27.National Research Council, Ed. Recommended Dietary Allowances. National Academy Press. Washington, DC. 1989. 28.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS. Calcium intake influences the association of protein intake with rates of bone loss in elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Apr;75(4):773-9. 29.Schurch MA, Rizzoli R, Slosman D, Vadas L, Vergnaud P, Bonjour JP. Protein supplements increase serum insulin-like growth factor-I levels and attenuate proximal femur bone loss in patients with recent hip fracture. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(10):801-9. 30.Scheiber MD, Liu JH, Subbiah MT, Rebar RW, Setchell KD. Dietary inclusion of whole soy foods results in significant reductions in clinical risk factors for osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease in normal postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2001;8(5):384-92. 31.Somekawa Y, Chiguchi M, Ishibashi T, Aso T. Soy intake related to menopausal symptoms, serum lipids, and bone density in postmenopausal Japanese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jan;97(1):109-15. 32.Watkins BA, Li Y, Lippman HE, Seifert MF. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and skeletal health. Exp. Biol. Med. 2001;226(6):485-97. 33. Carey BJ, Carey AH, Patel S, Carter G, Studd JW. A study to evaluate serum and urinary hormone levels following short and long ter m administration of two regimens of progesterone cream in postmenopausal women. BJOG. 2000;107(6):722-6. 34.O’Leary P, Feddema P, Chan K, Taranto M, Smith M, Evans S. Salivary, but not serum or urinary levels of progesterone are elevated after topical application of progesterone cream to pre- and postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000;53(5):615-20. 35.Leonetti HB, Longo S, Anasti JN. Transdermal progesterone cream for vaso-motor symptoms and post-menopausal bone loss. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(2):225-8. Summary The Food and Drug Administration has limited regulatory control of the over-the-counter vitamin, supplement, and botanical industry. Oversight, such as it is, is restricted to voluntary organizations that charge a fee for their review and certification of a product. United States Pharmacopeia (USP), Good Housekeeping Institute, and Consumerlab.com are three such entities. There are efforts on the part of these organizations to tighten and standardize their testing and certification procedures. However, the bottom line is still “buyer beware.” Additional information on non-FDA approved therapies is available from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complimentary and Alternative Medicine at http://altmed.od.nih.gov. In addition, consumer information on nutrition and dietary supplements is available at the FDA Dietary Supplement Questions and Answers web site at http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/ds-faq.html and the federal government’s nutrition website at http://www.nutrition.gov. References 1. Kanis JA. The use of calcium in the management of osteoporosis. Bone.1999;24(4):279-90. 2. Reid IR, Ames RW, Evans MC, Gamble GD, Sharpe SJ. Long-term effects of calcium supplementation on bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 1995;98(4):331-5. 3. Riggs LB, O’Fallon MW, Muhs J, O’Connor MK, Kumar R, Melton JL. Long-term effects of calcium supplementation on serum parathyroid hormone level, bone turnover, and bone loss in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(2):168-74. 4. Reid IR, Ames RW, Evans MC, Gamble GD, Sharpe SJ. Effect of calcium supplementation on bone loss in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(7):460-4. 5. Thomas MK, Lloyd-Jones DM, Thadhani RI, Shaw AC, Deraska DJ, Kitch BT, Vamvakas EC, Dick IM, Prince RL, Finkelstein JS. Hypovitaminosis D in medical inpatients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(12):777-83. 6. Binkley N, Krueger D. Hypervitaminosis A and bone. Nutr Rev. 2000;58:138-144. 7. Feskanich D, Singh V, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Vitamin A intake and hip fractures among postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;287:47-54. 8. New SA, Bolton-Smith C, Grubb DA, Reid DM. Nutritional influences on bone mineral density: A cross-sectional study in premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr.1997;65:1831-9. 9. Wang MC, Luz Villa M, Marcus R, Kelsey JL. Associations of vitamin C, calcium, and protein with bone mass in postmenopausal MexicanAmerican women. Osteoporosis Int. 1997;7(6):533-8. 10.Hall SL, Greendale GA. The relation of dietary vitamin C intake to bone mineral density: Results from the PEPI study. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;63(3):183-9. 11.Leveille SG, LaCroix AZ, Koepsell TD, Beresford SA, Van Belle G, Buchner DM. Dietary vitamin C and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women in Washington State, USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51(5):479-85. Close this window to return to the exam. ➐