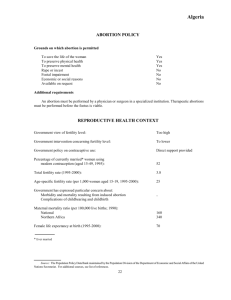

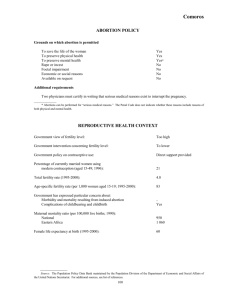

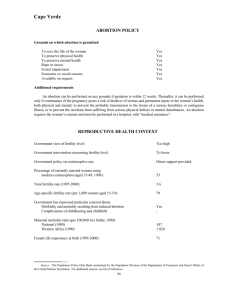

Therapeutic abortion in Nicaragua and El Salvador

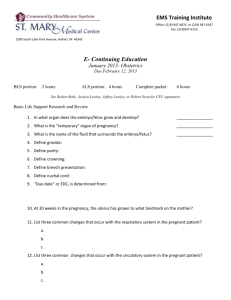

advertisement