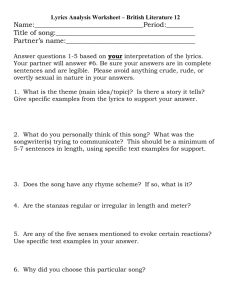

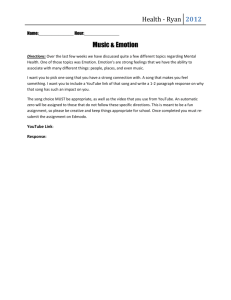

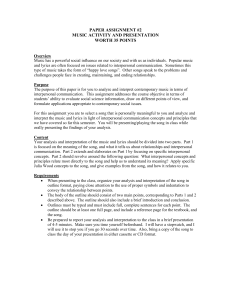

Popular music and communication in interpersonal relationships

advertisement