THE NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF THE JONES ACT

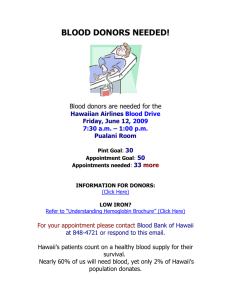

advertisement

The Negative Running head: THE NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF THE JONES ACT ON THE ECONOMY The Negative Effects of the Jones Act on the Economy of Hawaii Daniel Brackins Hawai’i Pacific University December 4, 2008 1 The Negative 2 The Negative Effects of the Jones Act on the Economy of Hawaii The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, commonly referred to as the Jones Act, is a United States Federal statute that regulates maritime commerce in U.S. waters and between U.S. ports. It is a cabotage law which also contains provisions regarding seamen’s rights. These cabotage provisions restrict the carriage of goods or passengers between U.S. ports to U.S. manufactured flagged vessels. In addition, it maintains that 75% of the crew members must be U.S. citizens. Also repair work of U.S. flagged vessels’ hulls and superstructures is limited to 10% of foreign built steel weight (1800JonesAct, 2008). These restrictions are largely American protectionist policies. These policies have a significant impact on the economy of the United States. Since Hawaii is an island which relies on trade and commerce for subsistence, the Jones Act has severe negative implications for the economy of Hawaii. No reliable analyses of the economic benefits of U.S. maritime polices have been published. Nor has there been a reliable study as to the benefits of a repeal of the Jones Act. As a result, judgment of these policies must be made by their rationale and their specific impact on certain economic sectors. Unfortunately there is even less information available for the economic impacts on the State of Hawaii. This paper will focus on the implications for the economy of Hawaii. It will demonstrate that costs for moving cargo between U.S. ports is far higher than if such restrictions did not apply, and that this cost is passed on to the consumer. It will also show that the U.S. shipbuilding industry has also suffered as a result of the Jones Act, and this it has prevented U.S. flagged ships from competing in international shipping. In addition a focus will be on the final implications for Hawaii’s consumers who bear the burden of this failed economic policy. Ultimately it will be shown what steps can be taken to reverse the The Negative negative impacts of the Jones Act and make Hawaii a prosperous state. Conclusions will be drawn from the general impact of the cabotage law on the United States and its effects on Hawaii. History and Purpose of the Jones Act The intent and purpose of the Jones Act has been codified in the preamble of the Act itself: It is necessary for the national defense and for the proper growth of its foreign and domestic commerce that the United States shall have a merchant marine of the best equipped and most suitable types of vessels sufficient to carry the greater portion of its commerce and serve as a naval or military auxiliary in time of war or national emergency, ultimately to be owned and operated privately by citizens of the United States; and it is declared to be the policy of the United States to do whatever may be necessary to develop and encourage the maintenance of such a merchant marine…(1800JonesAct, 2008) The history of the Jones Act must be evaluated in its historical context. At the turn of the century the United States was completing a process of development after overcoming the turmoil of the Civil War. It was at this time that strong and viable merchant fleet became a political priority. The British, known for a strong merchant fleet, were looked upon as a model because of their ascension to a position of dominant world power. This was attributed to having a strong naval fleet. Sir Walter Raleigh 3 The Negative stated, "Whosoever commands the sea commands trade; whosoever commands the trade of the world commands the riches of the world, and consequently the world itself” (McClintock, 2004). Another development was the need for American military forces to have a dependable sea lift capability in time of defense. This was realized during World War I. The infant U.S. Navy did not possess the capability of performing this function, and thus relied on the civilian sector for the transport of military cargo to overseas destinations. The volume of cargo and international trade for the U.S. merchant fleet had drastically decreased due to the economic decline and global turmoil caused by World War I. Further complicating the ability of the U.S. merchant fleet to compete in international commerce were higher construction and operation costs. For example, in 1926 the comparative monthly crew costs for ships of equal size were: $3,270 for the United States; $1,308 for Great Britain; and $777 for Japan. Historically, the United States curbed the impact of such issues through cabotage laws, which are government measures used to protect or foster a domestic shipping industry by reserving all or a portion of international sea commerce to ships which fly the national flag (McClintock, 2004). Cabotage laws were first introduced with the Shipping Act of 1916. The Shipping Act stated that only citizens of the United States, or companies in which a controlling interest was held by a citizen of the United States, could own a U.S. vessel. Additionally, the secretary of transportation had strict control over the transfer and chartering of U.S. vessels to foreign 4 The Negative 5 companies, and it provided for the regulation of rate agreements to avoid rate wars. Subsequently, Congress passed the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, which was arguably the nation's most influential cabotage law (McClintock, 2004). Proponent Argument In addition to national defense, proponents argue that the Jones Act provides additional benefits to the United States. Among these include job protection due to unfair competition by from other nations. Job Protection Phillip Grill (1996) says that job protected by the Jones Act is 124,000 (as cited in The Hidden Costs, 1996). Grill further says that these jobs must be protected in order to prevent the loss of jobs to foreign competitors, who charge less than fair wages for similar work done by U.S. workers. This is a claim to unfair competition. Indeed the wages of a merchant marine are incredibly high compared to their counterparts. A U.S. longshoreman or marine clerk can earn upwards of $100,000 to $137,000 per year (Longshoremen, 2002). Indeed this is a much greater salary found in such places as China. This increased cost of wages will be further analyzed. National Defense In the wars of this century, commercial shipping has been critically important. The relevant question is not whether future threats might require that fleets of commercial-type ships be available. The question is whether present programs provide such a capability The Negative 6 effectively and efficiently. If the U.S. flagged fleet is fully employed during peacetime serving commercially important domestic and international trades, it is neither an entirely reliable nor a low-cost military reserve. This was verified during the Gulf War (Ferguson, n.d.). Some security justification for transporting war material in peacetime exclusively on U.S. flagged ships is valid. The fact that a large fraction of military preference cargo consists of household goods and private automobiles dilutes any such basis for incurring the high costs of cargo preferences. Further, cargo preference does not buy much reserve military capability; the cargo preference largely supports bulk carriers and container ships that are of limited military use (Ferguson, n.d.). The higher than competitive prices that are permitted under the antitrust exemption for conference ratemaking may be important, given present regulatory constraints, in sustaining the U.S. flag fleet. However, more than 80 percent of traffic in American international liner commerce is carried by foreign companies. Therefore, whatever military gain is achieved through conference price fixing accrues predominantly to foreign governments (Ferguson, n.d.). The defense-related rationale for present policies presupposes that, despite the enormous capacity available on the open market, only U.S.-flag service could be relied on in an emergency. In contrast, the Military SealiftCommand made extensive use of foreign ships and crews in the Gulf War, and representatives of the Department of Defense have recently declared that there is no need to rely on the U.S.-flag commercial fleet in any foreseeable wars (Ferguson, n.d.). The Negative 7 Analysis Operating Cost Differentials Vessel costs are primarily comprised of capital and operating costs. Capital costs refer to vessel construction costs. Operating costs include wages paid to crews, direct fuel charges, insurance, maintenance and repair, and other administrative expenses. Of these, labor and maintenance costs are typically higher in absolute terms for U.S. vessels than for foreignflagged vessels (table 1). U.S. crew costs generally account for most of the differences in operating costs between U.S. and foreign flagged vessels. For example, manning costs account for 77 percent of the operating cost differential for a typical oil tanker and 81 percent of the cost differential for a typical containership (The Economic Effects, 2007). Table 1. Expense Category U.S. Flagged Foreign Flagged Crew 12,705 2,940 Fuel 4,410 3,045 Maint. & Repair 2,310 1,470 Insurance 13,335 13,335 Other 1,500 1,400 TOTAL $34,260 $22,190 Source: The Economic Effects, 2007 The Negative 8 The above table indicates a large crew expense for U.S. flagged ships. In addition to the higher salaries demanded, American ships must hire more crew members than foreign ships, often 23 or more, compared with as few as 11 on other vessels (Little, 2001). Even ship owners willing to pay American salaries say they were forced from the fleet because of all the other expenses that the U.S. flag requires. "Foreign crews eat less, they travel economy class, they seem to use less [provisions], there's less overtime, no workers complaints," said Vass, who re-flagged the LNG Aquarius. "I can't think of anything that didn't cost more. Like the beef. They would only eat prime American beef - not choice, like your wife feeds you, but prime, U.S. beef. We had to fly it out to Japan."I'm not saying the Americans aren't good. They are. But the foreign crew doesn't mind eating Australian beef" (Little, 2001). In the past 25 years 1,600 vessels have left the U.S. fleet (Little, 2001). In Hawaii many cattle ranchers have decided to use airplanes to ship their cattle. They find it cheaper and more efficient than shipping them on U.S. flagged ships. These cattle fly on 747s in livestock containers at 30 cents a pound (Little, 2001). They have no other choice since foreign flagged vessels are not allowed to ship cargo from one U.S. port to another. If foreign vessels were allowed to participate in U.S. cabotage, some industry analysts maintain that, in addition to complying with environmental laws, foreign vessels operating in U.S. domestic waters would be required to comply with other U.S. regulations, including federal and state tax, immigration, and labor laws. According to industry representatives, foreign vessel compliance with these laws likely would increase the costs of such vessels operating in Jones Act trade, thereby substantially decreasing the cost differential between U.S. and foreign The Negative flagged carriers. However, only some of these laws would apply to foreign vessels if they were allowed to participate in Jones Act trade (The Economic Effects, 2007). Job Protectionism and Unemployment As has been noted the U.S. shipping industry attempts to increases the wages of its employers with the use of the Jones Act. This is primarily accomplished through unions. A binding minimum wage can be introduced either by law or through collective bargaining, and its possible effects are shown in figure 2. 9 The Negative 10 Figure 1. The point of intersection of the supply and demand curves is the equilibrium point where supply equals demand. This point changes with shifts in the demand for labor (increase in demand for labor will increase price of labor). If labor markets were free to operate with no outside influence, then supply would equal demand, and all those who desired employment would be employed. We see that if the wage rate is higher than the equilibrium wage rate, the supply of labor will exceed the demand. By creating an artificial price floor for labor that is above the equilibrium wage rate, the supply of labor will exceed the demand (at that wage rate) and not all people who seek employment will be able to find a job. Note that if the wage is set below The Negative 11 the equilibrium wage, it will have no effect on the equilibrium point for the labor market (a nonbinding constraint). The higher the minimum wage above the equilibrium wage, the greater is the impact. The magnitude of the impact is also determined by the number of people who are currently being paid the minimum wage, and therefore directly affected by the change. Bargaining power obtained through the representation of large numbers of workers can result in wage rates that are well above the equilibrium rate. Often studies allude to cases where there appears to be little or no negative effects resulting from a minimum wage increase. These conclusions may occur due to the magnitude, timing, and number of employees impacted by the increase. There is an inability for unions to create wage equality through artificial wage inflation. In the unions’ attempt to equalize wages they have essentially done the opposite. An artificial increase in wages above the real market value assumes an infinite amount of monetary supply (Gallaway & Vetter, n.d.). With this failed logic it would be acceptable to pay a floor sweeper $50 per hour or perhaps $500 per hour. Yet the money supply is not unlimited; therefore, any shift will create a side effect. As a result any money given to one person must be taken from another. In the case of wage inequality it is wages that would have been given to another had the wages been determined by the market. Consider the graphical representation in figure 3. The Negative 12 Figure 2. Total industry workers possible: 5,000 5,000 Workers $10 per hour (Market Rate) 1,000 Workers $50 per hour (Artificial Rate) In the industry represented in the diagram there are a total of 5,000 jobs possible before saturation occurs. The market rate has established $10 per hour for this job and would allow for maximization and full employment. However, if an artificial rate were established at $50 per hour, as a result, only 1,000 workers could be utilized. This would prevent 4,000 workers from entering the industry. Decline of U.S. Shipping In comparison to other nations without cabotage restrictions there has been a decline in the U.S. shipping fleet, losing out to the competition of these other nations (Competition, 2006). The Negative 13 This is occurring despite the protectionist policies of the United States. A comparison of vessels operating can be seen in figures 3 and 4. Figure 3. Number of Registered Ships Source: Maritime Flags (2007) The Negative 14 Figure 4. Number of Foreign Registered Ships Source: Maritime Flags (2007) It must be noted that the protectionist policies of the U.S. has reduced the number of U.S. flagged ships in operation. On the other hand countries that exercise free trade policies, without cabotage laws, such as Panama, Singapore, and Hong Kong have a flourishing merchant fleet. Open competition has created incentives for companies to operate in these nations. Even U.S. shipping companies are aware of this benefit. Despite having to pay a 36% penalty fee under Jones Act laws, Matson has some of its ships repaired in Shanghai, China. Matson spokeman Jeff Hull stated, “[despite the fee] it’s still considerably cheaper” (Little, 2001). The Negative 15 Subsidy Costs The U.S. government pays out $100 million in ship subsidies every year and underwrites more than $1 billion in loans. It spends half a billion dollars a year on the added cost of shipping its cargo on American vessels and employs an entire government agency to preserve the U.S. merchant marine. American ships are still the most expensive in the world despite these efforts (Little, 2001). This increased cost forces shipping companies in other nations to purchase vessels from nations such as Norway where they are cheaper. Foreign Aid and U.S. Farmers The Jones Act is causing Midwest farmers to lose markets for grain. North Carolina poultry and pork farmers have been unable to find Jones Act vessels to ship grain from the Midwest. As a result, some North Carolina farmers are importing foreign grain on foreignflagged and owned ships (The Hidden Costs, n.d.). Another set of shipping laws with an impact on American farmers is the cargo preference laws which require that certain portions of United States government cargo must be shipped on U.S.-flagged vessels. Cargo preference provisions state that at least 75 percent of food aid provided to foreign countries under Titles I, II, and III of the Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954 (also known as P.L. 480 or Food for Peace) or section 416 of the Agricultural Act of 1949 must be shipped on U.S.-flagged ships (The Hidden Costs, n.d.). The United States General Accounting Office (GAO) reports that shipping food assistance on U.S.-flagged ships rather than on the lowest-priced ships costs the U.S. about The Negative 16 $150 million per year. Increasing the costs of shipping food to foreign countries reduces the amount of grain that can be shipped to hungry people under a set budget. In addition, this reduces the amount of grain the government can purchase from Midwest farmers for food aid (The Hidden Costs, n.d.). Cost of Food in Hawaii Table 2 shows the significant differences in the cost of food between Hawaii and the mainland. Because in Hawaii 90% of goods are imported there is a significant impact as a result of protectionist policies in the islands. Table 2. Cost of Food Based on a Thrifty Plan Mainland Hawaii Difference Male 20-50 $174.00 $251.60 30.8% Female 20-50 $154.90 $231.00 32.9% Family of Two $361.80 $530.80 31.8% Family of Four $602.80 $905.10 33.4% Source: Official USDA Food, 2008; Official USDA Alaska, 2008 The Negative 17 Table 2 shows the significant increase in costs between the mainland and Hawaii. These costs can be attributed to the significant correlation between the cost of shipping and higher prices of food in Hawaii. Cost of Living in Hawaii The cost of food in Hawaii has been offset to some degree with the arrival of major warehouse outlets throughout the islands (e.g. Costco, Sam's Club, Wal-Mart). Despite this, a cost of living analysis of Honolulu shows that the cost of consumables weighted to pricing patterns of grocery and drug store chains is as much as 66% more than the U.S. average; depending upon family size, earnings level and spending patterns. In addition it was noted that a family of 4 renting accommodation in Honolulu needs to earn $111,695 or 55% more income to maintain a lifestyle similar to a comparable family earning $72,000 in the continental United States (The Price, n.d.). Benefits of Repeal The have been few estimates on the costs of the Jones Act, while none provide an estimate as to how much the State of Hawaii would benefit. As a result no figure for Hawaii can be given or estimated here. However it is possible to show the potential loss to the United States as a whole. The International Trade Commission (ITC) in a 1993 study indicated that the Jones Act costs the United States a total of $3.1 billion per year (Ferguson, n.d.). In their most recent study the ITC stated it was, “unable to provide an estimate of the welfare gains that would result from removing these [sic] restraints” (The Economic Effects, 2007). However the The Negative 18 ITC was able to estimate a complete removable all trade restraints in the U.S. as shown in table 3. Table 3. Possible Solutions The free trade nations of Hong Kong and Singapore have received enormous benefits because of their policies. These nations suffer from the similar circumstances of Hawaii in that they lack natural resources and confined to a small land mass. Despite these circumstances their policies have allowed them to prosper. The policies employed by these nations include free trade zones and an absence of cabotage restrictions. Table 4 shows a comparison of Hawaii to these nations. The Negative 19 Table 4. Singapore Hong Kong Hawai’i Area 270 sq mi 426 sq mi 10,931 sq mi Population 4,588,600 6,985,389 1,283,388 Density 16,392 sq mi 16,469 sq mi 189 sq mi GDP $228.1 billion $292.8 billion $49.9 million GDP per capita $49,714 $41,994 $38,820 Freedom Index 8.8 8.9 6.1 Free Trade Yes Yes No Source: The World Factbook, 2008 The evidence suggests that the more economically free a nation is, the more prosperous it becomes. It should be investigated whether or not similar free trade policies will benefit the State of Hawaii. Conclusion Using the evidence compiled in regards to the impact of the Jones Act on the United States as a whole, coupled with various economic indicators of the State of Hawaii, certain conclusions can be drawn. These conclusions show that the Jones Act has a negative effect on the U.S. economy as a whole. Since Hawaii relies more heavily on shipping than its mainland The Negative 20 counterparts, the negative effect is amplified. It would certainly benefit the State of Hawaii to remove such restriction on trade and allow for free market competition. While the benefits cannot be quantified, reason would indicate such benefits undoubtedly exist. It must be further investigated whether or not similar trade polices used in Singapore and Hong Kong would benefit Hawaii. The Negative 21 References 1800JonesAct. (2008). The Jones Act U.S.C. Title 46 (Recodified 2006). Retrieved November 21, 2008 from http://www.1800jonesact.com/maritime_statutes/default.asp Competition in the Noncontiguous Domestic Maritime Trades (2006). U.S. Department of Transportation Maritime Administration. Little, R. (2001). U.S. merchant fleets sails toward oblivion. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 1, 2008 from http://www.mcall.com/topic/balte.bz. sealift06aug06,0,7707946.story?page=1 Longshormen, Making $100K Per Year, Won’t Reduce Demands (2002). Rense.com. Retrieved September 29, 2008 from http://www.rense.com/general30/long.htm Maritime Flags of Convenience Visualized (2007). gCaptain. Retrieved September 29, 2008 from http://gcaptain.com/maritime/blog/tag/data/ McClintock, M. (2004). Merchant Marine Act of 1920. eNotes.com. Retrieved October 2, 2008 from http://www.enotes.com/major-acts-congress/merchant-marine-act Official USDA Alaska and Hawaii Thrifty Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home (2008). United States Department of Agriculture. Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels (2008). United States Department of Agriculture. The Negative The Economic Effects of Significant U.S. Import Restrains Fifth Update 2007 Investigation No. 332-325 (2007). United States International Trade Commission. The Hidden Costs of U.S. Shipping Laws (1996). Public Interest Institute. The Price of Paradise! (n.d.). Alternative-Hawaii. Retrieved October 1, 2008 from http://www.alternative-hawaii.com/overpop.htm The World Factbook (2008). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved October 2, 2008 from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ 22