Your Right to Communicate With the Outside

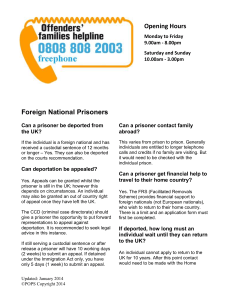

advertisement