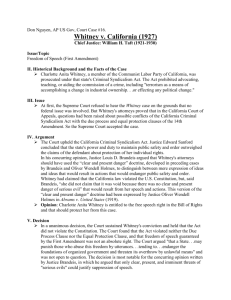

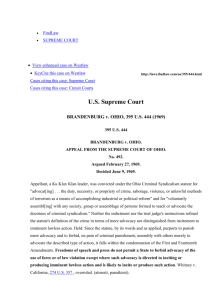

Whitney v. California (1927)

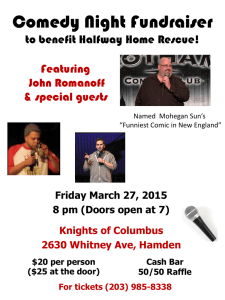

advertisement

Whitney v. California (1927) Background In 1919 California passed the Criminal Syndicalism Act, which made membership illegal in an organization that advocates commission of crimes as a means of effecting political change. The term “criminal syndicalism” is defined as “any doctrine or precept advocating, teaching or aiding and abetting the commission of crime, sabotage . . . or unlawful acts of force and violence or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing a change in industrial ownership or control, or effecting any political change.” Charlette Whitney, a member of the Communist Labor Party of California, was indicted for having violated the Criminal Syndicalism Act by having taken part in organizing the party and being a member of it. At her trial, the Communist Labor Party was found to have been organized to advocate, teach, and abet criminal syndicalism. Whitney was convicted and sentenced to prison. Her conviction was upheld in the District Court of Appeals. Whitney then appealed her conviction to the Supreme Court on the grounds that she had been denied her Fourteenth Amendment rights of due process, including her right of free speech. Constitutional Issue In the case of Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court adopted the clear and present danger principle as the basis for deciding whether, under certain circumstances, a law banning certain kinds of speech could be considered constitutional. The Schenck case, however, arose when the United States was involved in World War I. Would the same principle apply when the constitutionality of a law that banned certain kinds of speech in peacetime was challenged? The Court had decided that a federal law of this sort was valid in the case of Gitlow v. United States in 1925. In that case the Court had invoked not the clear and present danger principle, but a new one, called the bad tendency doctrine. Now, two years later, the Court had to decide whether the California Criminal Syndicalism Act could limit free speech as it did without violating a person’s constitutional rights under the due process provision of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court’s Decision The Court upheld Whitney’s conviction by declaring the California law constitutional. Justice Edward Sanford wrote the Court’s opinion finding that California’s Syndicalism Act as applied in this case was not “. . . repugnant to the due process clause as a restraint of the rights of free speech, assembly, and association. ”He invoked the bad tendency test as the standard by which to evaluate speech cases. He held that “. . . the freedom of speech which is secured by the Constitution does not confer an absolute right to speak, without responsibility, whatever one may choose, or an unrestricted and unbridled license giving immunity for every possible use of language and preventing the punishment of those who abuse this freedom, and that a State in the exercise of its police power may punish those who abuse this freedom by utterances inimical to the public welfare, tending to incite to crime, disturb the public peace, or endanger the foundations of organized government and threaten its overthrow by unlawful means. . . .” He added that “united and joint action involves even greater danger to the public peace and security than the isolated utterances and acts of individuals. . . .” Justice Louis D. Brandeis, joined by Justice Holmes, issued a concurring opinion in which he agreed with the Court’s decision for technical reasons, but forcefully invoked the clear and present danger principle. He pointed out, “Whenever the fundamental rights of free speech and assembly are alleged to have been invaded, it must remain open to a defendant to present the issue whether there actually did exist at the time a clear danger; whether the danger, if any, was imminent, and whether the evil apprehended was one so substantial as to justify the stringent restriction imposed by the legislature. . . .” In this case, however, he noted that Whitney had not claimed that there was no clear and present danger, and there was evidence from which a jury could find that such a danger existed. He wrote: “To courageous, self-reliant men, with confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning applied through the processes of popular government, no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present, unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. If there be time . . . to avert the evil by the process of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.” He added, “The fact that speech is likely to result in some violence or in destruction of property is not enough to justify its suppression. There must be the probability of serious injury to the state.” The Court’s decision in the Whitney case was overruled in 1969 in Brandenburg v. Ohio. Questions for Analysis and Debate 1. Do you think Charlette Whitney had the right to say whatever she wanted, even if her words provoked violence? 2. Can you think of a situation when a person’s right to free speech should be suppressed for any reason? 3. Choose a side in this case to argue for. Choose to argue for Charlette Whitney or the state of California. Once you have chosen a side, make a list of arguments for your side of the case. As a class, split up sides and debate this issue. Was the Court justified in upholding Whitney’s conviction? Should Whitney’s right to free speech have been protected in this case?