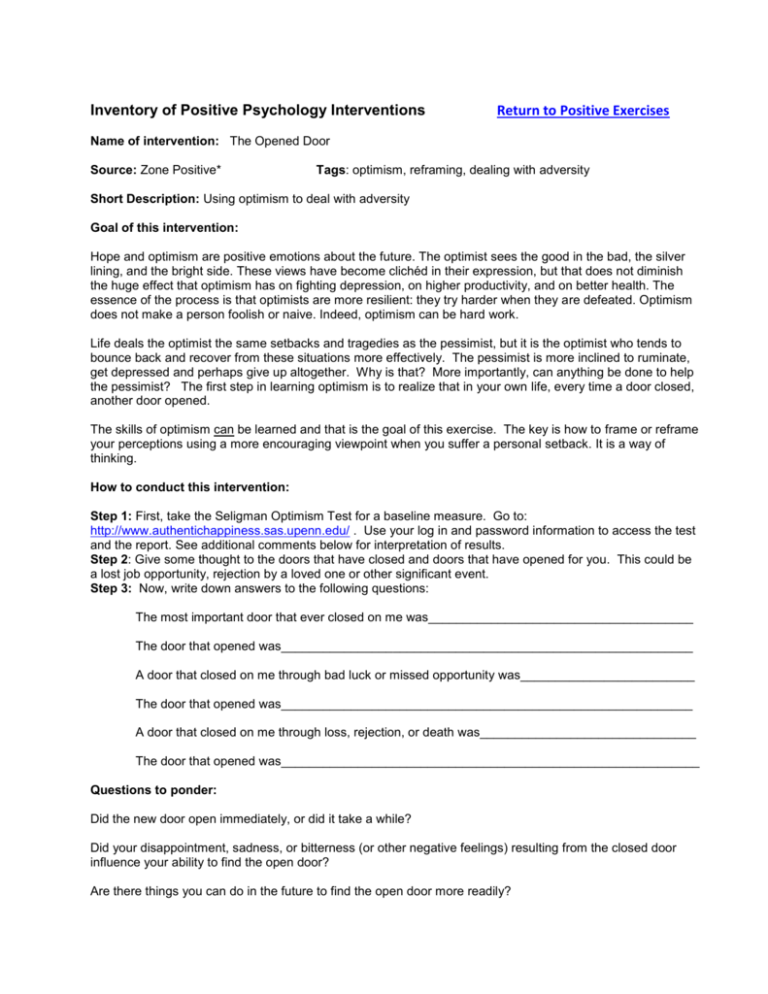

Inventory of Positive Psychology Interventions

advertisement

Inventory of Positive Psychology Interventions Return to Positive Exercises Name of intervention: The Opened Door Source: Zone Positive* Tags: optimism, reframing, dealing with adversity Short Description: Using optimism to deal with adversity Goal of this intervention: Hope and optimism are positive emotions about the future. The optimist sees the good in the bad, the silver lining, and the bright side. These views have become clichéd in their expression, but that does not diminish the huge effect that optimism has on fighting depression, on higher productivity, and on better health. The essence of the process is that optimists are more resilient: they try harder when they are defeated. Optimism does not make a person foolish or naive. Indeed, optimism can be hard work. Life deals the optimist the same setbacks and tragedies as the pessimist, but it is the optimist who tends to bounce back and recover from these situations more effectively. The pessimist is more inclined to ruminate, get depressed and perhaps give up altogether. Why is that? More importantly, can anything be done to help the pessimist? The first step in learning optimism is to realize that in your own life, every time a door closed, another door opened. The skills of optimism can be learned and that is the goal of this exercise. The key is how to frame or reframe your perceptions using a more encouraging viewpoint when you suffer a personal setback. It is a way of thinking. How to conduct this intervention: Step 1: First, take the Seligman Optimism Test for a baseline measure. Go to: http://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/ . Use your log in and password information to access the test and the report. See additional comments below for interpretation of results. Step 2: Give some thought to the doors that have closed and doors that have opened for you. This could be a lost job opportunity, rejection by a loved one or other significant event. Step 3: Now, write down answers to the following questions: The most important door that ever closed on me was______________________________________ The door that opened was___________________________________________________________ A door that closed on me through bad luck or missed opportunity was_________________________ The door that opened was___________________________________________________________ A door that closed on me through loss, rejection, or death was_______________________________ The door that opened was____________________________________________________________ Questions to ponder: Did the new door open immediately, or did it take a while? Did your disappointment, sadness, or bitterness (or other negative feelings) resulting from the closed door influence your ability to find the open door? Are there things you can do in the future to find the open door more readily? What have you learned from this exercise? How might you apply next time you are faced with a setback? Expected outcome (examples) People have different ways of reacting to adversity such as failure, rejection or a high-pressure situation. Individuals with high Overall Optimism Scores are more likely to have the following characteristics than those with low Overall Optimism Scores: -Are self-motivated, confident, resourceful, assertive and decisive -Are resilient and are not overwhelmed by adversity -Rebound quickly following defeats -Cope well with frequent frustration, rejection and stress -Persevere in finding solutions to difficult problems -Are unlikely to be undermined by off-the job problems -Do not dwell on or punish themselves over failures -Maintain confidence, determination and enthusiasm following setbacks -Are energized by success to seek out more challenges and opportunities -Believe success is achievable Things to watch out for You may argue that supporting optimism means sacrificing realism. Remember to be flexible. We are not suggesting that absolute, unconditional optimism be applied blindly in all situations. This exercise simply aims to increase your control over the way you think about adversity. You may think that learning to be optimistic feels superficial—an attempt to change your personality and turn yourself into “Miss Goody Two-Shoes”. You may resist. Use the same point as explained in the bullet above. Is there any science to support this intervention Many studies have been done on the various facets of optimism. One study for example looked at optimism and coping behavior (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989). Results showed that optimists tend to be problem focused and plan-oriented. They tend to accept the reality of stressful events, try to see the best in bad situations and they try to learn something from them (finding benefits in adversity). By comparison, pessimists tend to disengage from the goals when the situation becomes stressful. They tend toward overt denial and reduced awareness of the problem. They tend to avoid acceptance of the situation, using more emotion-focused coping including escapism (i.e. eating, drinking). Additional comments: Interpreting the results of the Optimism Test: Optimists: People who believe good events have a permanent cause are more optimistic than those who believe they have temporary causes. If your score is 7 or 8, you are very optimistic about the likelihood of good events continuing; 6, moderately optimistic; 4 or 5, average; 3, moderately pessimistic; and 0, 1, or 2, very pessimistic. The optimist believes good events will enhance everything he does, while the pessimist believes good events are caused by specific factors. If your score is 7 or 8, you are very optimistic; 6, moderately optimistic; 4 or 5, average; 3, moderately pessimistic; and 0, 1, or 2, very pessimistic Pessimists: People who give up easily believe the causes of the bad events that happen to them are permanent—the bad events will persist, are always going to be there to affect their lives. People who resist helplessness believe the causes of bad events are temporary. If your score is 0-1, you are very optimistic on this dimension; 2 or 3, moderately optimistic; 4 average, 5 or 6 quite pessimistic; and if you got a 7 or 8 you are very pessimistic. People who make universal (pessimistic) explanations for their failures give up on everything when a failure strikes in one area. People who make specific (optimistic) explanations may become helpless in that one part of their lives, yet march stalwartly on in others. If your score is 0-1, you are very optimistic on this dimension; 2 or 3, moderately so; 4 average, 5 or 6 quite pessimistic; and if you got a 7 or 8 very pessimistic Whether or not we have hope depends on the two dimensions of Permanence and Pervasiveness taken together. Finding permanent and universal causes of good events along with temporary and specific causes for misfortune is the art of hope finding permanent and universal causes for misfortune and temporary and specific causes of good events is the practice of despair. If your score is 10 to 16, you are extraordinarily hopeful; 6 to 9, moderately hopeful; from 1 to 5, average, from minus 5 to 0, moderately hopeless; and below minus 5, severely hopeless. Note: Questionnaires like this are not infallible and do not predict the future with certainty, they simply give statistical probabilities. Only the Overall Optimism Score has been statistically validated for personnel selection purposes -- for selecting salespeople. All other scores should be used only for personnel training and development purposes. If the Overall Optimism Score is used for selecting salespeople, it should not be used as the sole basis for any hiring decision, but is intended for use in conjunction with other valid selection methods. Research has shown that, on the average, individuals with high optimism will significantly out produce those with low optimism. Readings: Seligman, M. E. P., (2006). Learned Optimism. New York: Random House, Inc. Seligman, M.E.P. (2002). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: Free Press. References: Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267-283. *Adapted from the “What door opened” exercise, Martin E. P. Seligman Ph.D. - University of Pennsylvania Return to Positive Exercises