People of the State of California v. Marjorie Knoller

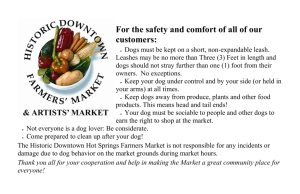

advertisement