Divergent Effects of Joyful and Anxiety

advertisement

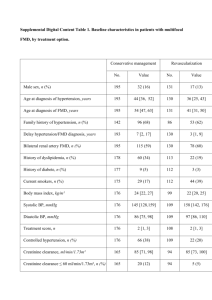

Divergent Effects of Joyful and Anxiety-Provoking Music on Endothelial Vasoreactivity MICHAEL MILLER, MD, C. CHARLES MANGANO, BA, RDMS, VALERIE BEACH, RN, WILLEM J. KOP, PHD, AND ROBERT A. VOGEL, MD Objective: To evaluate the extent to which music may affect endothelial function. In previous research, a link between music and physiologic parameters such as heart rate and blood pressure has been observed. Methods: Randomized four-phase crossover and counterbalanced trial in ten healthy, nonsmoking volunteers (70% male; mean age, 35.6 years) that included self-selections of music evoking joy or provoking anxiety. Two additional phases included watching video clips to induce laughter and listening to audio tapes to promote relaxation. To minimize emotional desensitization, subjects were asked to refrain from using self-selected tapes and images for at least 2 weeks before the assigned study phase. Endothelial function was assessed by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and measured as percent diameter change after an overnight fast. After baseline FMD measurements, subjects were randomized to a 30-minute phase of the testing stimulus followed by poststudy FMD; they returned a minimum of 1 week later for the subsequent task. A total of 160 FMD measurements were obtained. Results: Compared with baseline, music that evoked joy was associated with increases in mean upper arm FMD (2.7% absolute increase; p ⬍ .001), whereas reductions in FMD were observed after listening to music that elicited anxiety (0.6% absolute decrease; p ⫽ .005 difference between joyful and anxiety-provoking music). Self-selected joyful music was associated with increased FMD to a magnitude previously observed with aerobic activity or statin therapy. Conclusion: Listening to joyful music may be an adjunctive life-style intervention for the promotion of vascular health. Key words: endothelial function, brachial artery reactivity testing, music, laughter. FMD ⫽ flow-mediated dilation. INTRODUCTION sychosocial stress is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, which is partially related to stressinduced endothelial dysfunction (1). However, fewer studies have evaluated the extent to which positive emotions may affect the endothelium. We demonstrated that cinematic viewing of movie and television segments that evoked laughter was associated with improved endothelial flow-mediated dilation (FMD) as compared with video images inducing mental stress (2). Because positive emotions, such as laughter, are associated with release of natural opioid compounds (i.e., -endorphin) that up-regulate production of endotheliumderived nitric oxide (3), we hypothesized that other emotional stimuli may affect endothelial function. Brachial artery reactivity testing has been used as a noninvasive surrogate of endothelial function. FMD is correlated with the intracoronary vasomotor response post acetylcholine administration (4,5), and reduced endothelial vasoreactivity has been consistently identified in subjects with diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, cigarette smoking, and hypertension (1). Similar effects have also been observed in response to mental stress or depression (6), raising the possibility that positive emotions may exert an opposite effect on FMD. To this end, we previously found that laughter improved FMD (2) and a P From the Division of Cardiology, University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Michael Miller, MD, Division of Cardiology, University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, MD 21201. E-mail: mmiller@medicine.umaryland.edu Received for publication September 9, 2009; revision received December 4, 2009. Dr. Miller had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This study was supported, in part, by Grant RO1HL61369 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interests. DOI: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181da7968 354 0033-3174/10/7204-0354 Copyright © 2010 by the American Psychosomatic Society recent study (7) reported improvement in arterial stiffness as measured by pulse-wave velocity after induction of laughter. The aim of the present study was to further evaluate positive and negative stimuli and their potentially divergent effects on FMD. METHODS Ten nonsmoking, normotensive, and normolipidemic men (n ⫽ 7) and women (n ⫽ 3), aged 35.6 ⫾ 12.0 years, without a history of metabolic or psychiatric disease were enrolled in this four-phased, randomized, counterbalanced, crossover study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland Medical Center; all participants provided their written informed consent. The study was conducted between July 2006 and January 2007. The four-phased study included 1) musical selections causing feelings of joyfulness; 2) musical selections causing feelings of anxiety; 3) video segments causing laughter; and 4) audio tapes involving deep breathing and other guided relaxation exercises. Musical and video choices were self-selected based on a prior history of positive or negative emotional experiences to these selections. For example, joyful musical selections were defined as having created a sense of well-being or euphoria, whereas negative musical selections were based on prior induction of anxiety. Similarly, examples of videos that previously promoted laughter included clips from Saturday Night Live (NBC), Shallow Hal (20th Century Fox, 2001), and others (2). Finally, the audio tape used for the relaxation phase was guided by visual and auditory imagery that volunteers had been exposed to before study entry. Each phase was separated by a minimum of 1 week, and the volunteers were asked not to listen to or watch the selections for a minimum of 2 weeks before testing. On the morning of testing and after an overnight fast, endothelial-dependent FMD was assessed by brachial artery reactivity testing. Baseline FMD images (pre and post occlusion) were acquired with the subject in a recumbent position and temperature-controlled room (22°C) (4) for each of the four phases. Subsequently, volunteers listened to or viewed selections for 30 minutes after which poststimulus FMD images (pre and post occlusion) were acquired. Brachial artery images were obtained, using an 11-MHz to 5-MHz broadband linear-array transducer. One dedicated research ultrasonographer performed all (baseline and post stimulus) studies. Images were acquired 1 minute ⫾ 15 seconds after releasing the blood pressure cuff after 5 minutes of upper-arm occlusion. For each phase, a total of four FMD images (pre and post occlusion at baseline and after study stimuli) were collected. Therefore, each volunteer underwent 16 FMD images for a total of 160 arterial measurements during the study. FMD was quantified as percent diameter difference between baseline and post occlusion arterial diameter; end-diastolic Psychosomatic Medicine 72:354 –356 (2010) MUSIC AND ENDOTHELIAL VASOREACTIVITY frames were analyzed by a single investigator who was blinded to the identity and study phase. Data are presented as mean ⫾ standard error of the mean or percentages as appropriate. Study phase-induced responses in FMD were examined, using a 2 ⫻ 4 repeated-measures analyses of variance with two within-subject factors: a) study phase response (baseline versus phase); and b) type of study phase (joyful music, anxiety-provoking music, relaxation, and laughter). A significant “response ⫻ type of phase” interaction was used as indicator of differential responses to the study phases. Post hoc paired t tests were used to examine responses to each of the four phases individually. A p ⬍ .05 was considered statistically significant. RESULTS Results for baseline and study phase-induced FMD are presented in Table 1. Analysis of variance indicated that responses differed significantly across the four positive provocation phases (Finteraction(3,7)) ⫽ 4.64, p ⫽ .043 and a marginally significant main effect for response from baseline to study phase (F(1,9) ⫽ 4.28, p ⫽ .068). Analyses per phase revealed significant vasodilation in response to the joyful music (p ⬍ .001) and a marginally significant response to laughter (p ⫽ .08), whereas responses to anxiety-provoking music (p ⫽ .37) and relaxation (p ⫽ .46) were nonsignificant. Figure 1 illustrates individual FMD responses at baseline and after listening to joyful or anxiety-provoking music for 30 minutes. Nine of ten volunteers experienced increased FMD TABLE 1. Mean (ⴞStandard Error) Percent Change in Brachial Artery Flow-Mediated Vasodilation at Baseline and After Each Study Phase Joyful music Laughter Anxious music Relaxation Figure 1. Baseline Post p 10.12 (1.42) 10.68 (1.63) 10.65 (1.39) 10.58 (1.16) 12.78 (1.46) 12.73 (1.40) 10.04 (1.44) 11.72 (1.66) ⬍.001 .08 .37 .46 (2.7% absolute increase; p ⬍ .001) after listening to joyful music. The mean FMD after listening to joyful music was significantly larger than the FMD response to anxiety-provoking music (p ⫽ .005). The pattern of results was not confounded by drift in the pre task baseline FMD (p ⫽ .88), and mean baseline diameters before each of the four phases (pre laughter, 3.28 ⫾ 0.70 mm [range, 2.50 – 4.46]; prejoyful music, 3.34 ⫾ 0.70 mm [range, 2.47– 4.56]; pre anxious music, 3.24 ⫾ 0.64 mm [range, 2.47– 4.24]; pre relaxation, 3.21 ⫾ 0.64 mm [range, 2.50 – 4.37]), suggesting internal technical consistency in image acquisition and subject compliance with protocol requirements. DISCUSSION The present study shows that music results in improved endothelial function as measured by flow-mediated vasodilation. In addition to the autonomic variables induced by rhythm and tempo effects (8), we found that musical compositions that were self-selected on the basis of being joyful or anxiety-provoking support a physiologic role for music that is broadened beyond effects previously observed on blood pressure and heart rate (9). Although the mechanism(s) underlying the effect of positive emotions on endothelial vasoreactivity remains to be elucidated, one possible link is -endorphin-mediated activation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide, an effect opposite to that observed in response to mental stress when the potent vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 is released (10). Other biomarkers associated with music listening include oxytocin secretion (11). There are potential limitations associated with the study. First, brachial artery diameter was measured at 1 minute ⫾ 15 seconds after release of cuff pressure, and this interval may have been too short to capture the maximum rate of dilation in some individuals due to interindividual variability. However, because each subject served as his/her control for all four study phases, the absence of maximal dilation would have Brachial artery flow-mediated dilation at baseline and after listening to joyful or anxiety-provoking music for 30 minutes. Psychosomatic Medicine 72:354 –356 (2010) 355 M. MILLER et al. been expected to occur consistently after each of the randomized phases. Nevertheless, this potential shortcoming can be overcome in future studies, using modern software that precisely captures peak FMD. In addition, although we did not specifically address the potential painful effects of brachial artery occlusion for 5 minutes, it is plausible that an abnormal endothelial response to this iatrogenic stressor may have been attenuated after listening to joyful music (12). In summary, the ⬎2.5% absolute change in FMD observed between joyful and anxiety-provoking music is suggestive of meaningful differences between the conditions (13) and raises the possibility that positive emotions beneficially affect vascular health. However, the clinical implications of these effects require further study. REFERENCES 1. Glasser SP, Selwyn AP, Ganz P. Atherosclerosis: risk factors and the vascular endothelium. Am Heart J 1996;131:379 – 84. 2. Miller M, Mangano C, Park Y, Goel R, Plotnick GD, Vogel RA. Impact of cinematic viewing on endothelial function. Heart 2006;92:261–2. 3. Stefano GB, Hartman A, Bilfinger TV, Magazine HI, Liu Y, Casares F, Goligorsky MS. Presence of the mu3 opiate receptor in endothelial cells. Coupling to nitric oxide production and vasodilation. J Biol Chem 1995; 270:30290 –3. 356 4. Corretti MC, Plotnick CD, Vogel RA. Technical aspects of evaluating brachial artery vasodilation using high-frequency ultrasound. Am J Physiol 1995;268:H1397– 404. 5. Anderson TJ, Uehata A, Gerhard MD, Meredith IT, Knab S, Delagrange D, Lieberman EH, Ganz P, Creager MA, Yeung AC, Selwyn AP. Close relation of endothelial function in the human coronary and peripheral circulations. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26:1235– 41. 6. Gottdiener JS, Kop WJ, Hausner E, McCeney MK, Herrington D, Krantz DS. Effects of mental stress on flow-mediated brachial arterial dilation and influence of behavioral factors and hypercholesterolemia in subjects without cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2003;92:687–91. 7. Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Alexopoulos N, Aznaouridis K, Vasiliadou C, Baou K, Stefanadi E, Stefanadis C. Divergent effects of laughter and mental stress on arterial stiffness and central hemodynamics. Psychosom Med 2009;71:446 –53. 8. Bernardi L, Porta C, Casucci G, Balsamo R, Bernardi NF, Fogari R, Sleight P. Dynamic interactions between musical, cardiovascular, and cerebral rhythms in humans. Circulation 2009;119:3171– 80. 9. Bradt J, Dileo C. Music for stress and anxiety reduction in coronary heart disease patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;2:CD006577. 10. Nickel T, Deutschmann A, Hanssen H, Summo C, Wilbert-Lampen U. Modification of endothelial biology by acute and chronic stress hormones. Microvasc Res 2009;78:364 –9. 11. Nilsson U. Soothing music can increase oxytocin levels during bed rest after open-heart surgery: a randomised control trial. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:2153–61. 12. Chafin S, Roy M, Gerin W, Christenfeld N. Music can facilitate blood pressure recovery from stress. Br J Health Psychol 2004;9:393– 403. 13. Sorensen KE, Celermajer DS, Spiegelhalter DJ, Georgakopoulos D, Robinson J, Thomas O, Deanfield JE. Non-invasive measurement of human endothelium dependent arterial responses: accuracy and reproducibility. Br Heart J 1995;74:247–53. Psychosomatic Medicine 72:354 –356 (2010)