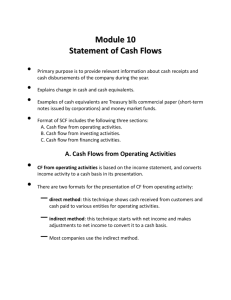

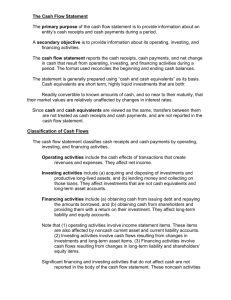

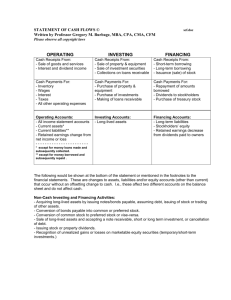

Cash Flow - CT Capital LLC

advertisement