Brief for Petitioner in Roper v. Simmons, 03

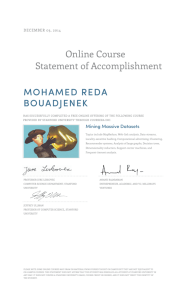

advertisement