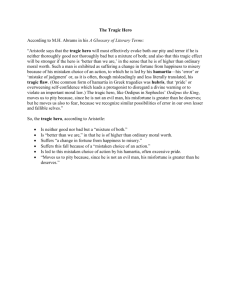

Hamartia & the “Tragic Flaw” – Misinterpretations of Aristotle From

advertisement

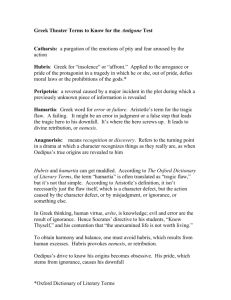

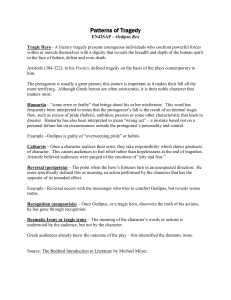

Hamartia & the “Tragic Flaw” – Misinterpretations of Aristotle From http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/lit_terms_H.html#hamartia_anchor HAMARTIA: A term from Greek tragedy that literally means "missing the mark." Originally applied to an archer who misses the target, a hamartia came to signify a tragic flaw, especially a misperception, a lack of some important insight, or some blindness that ironically results from one's own strengths and abilities. In Greek tragedy, the protagonist frequently possesses some sort of hamartia that causes catastrophic results after he fails to recognize some fact or truth that could have saved him if he recognized it earlier. The idea of hamartia is often ironic; it frequently implies the very trait that makes the individual noteworthy is what ultimately causes the protagonist's decline into disaster. From Wikieducator.org 1.7.3 What does he mean by Hamartia? What is this error of judgement. The term Aristotle uses here, hamartia, often translated “tragic flaw,”(A.C.Bradely) has been the subject of much debate. Aristotle, as writer of the Poetics, has had many a lusty infant, begot by some other critic, left howling upon his doorstep; and of all these (which include the bastards Unity-of-Time and Unity-of-Place) not one is more trouble to those who got to take it up than the foundling ‘Tragic Flaw’. Humphrey House, in his lectures (Aristotle’s Poetics, ed. Colin Hardie (London, 1956), p.94) delivered in 1952-3, commented upon this tiresome phrase: “The phrase ‘tragic flaw’ should be treated with suspicion. I do not know when it was first used, or by whom. It is not an Aristotelian metaphor at all, and though it might be adopted as an accepted technical translation of ‘hamartia’ in the strict and properly limited sense, the fact is that it has not been adopted, and it is far more commonly used for a characteristic moral failing in an otherwise predominantly good man. Thus, it may be said by some writers to be the ‘tragic flaw’ of Oedipus that he was hasty in temper; of Samson that he was sensually uxorious; of Macbeth that he was ambitious; of Othello that he was proud and jealous – and so on … but these things do not constitute the ‘hamartia’ of those characters in Aristotle’s sense.” Mr. House goes on to urge that ‘all serious modern Aristotelian scholarship agrees … that ‘hamartia’ means an error which is derived from ignorance of some material fact or circumstance, and he refers to Bywater and Rostangni in support of his view. But although ‘all serious modern scholarship’ may have agreed to this point in 1952-3, in 1960 the good news has not yet reached the recesses of the land and many young students of literature are still apparently instructed in the theory of the ‘tragic flaw; a theory which appears at first sight to be a most convenient device for analyzing tragedy but which leads the unfortunate user of it into a quicksand of absurdities in which he rapidly sinks, dragging the tragedies down with him. In his edition of Aristotle on the Art of Poetry (Oxford, 1909), Ingram Bywater refers to such a misreading, though without using the term ‘tragic flaw’: “Hamartia in the Aristotelian sense of the term is a mistake or error of judgement (error in Lat.), and the deed done in consequence of it is an erratum. In the Ethics an errtum is said to originate not in vice or depravity but in ignorance of some material fact or circumstance … this ignorance, we are told in another passage, takes the deed out of the class of voluntary acts, and enables one to forgive or even pity the doer.” The meaning of the Greek word is closer to “mistake” than to “flaw,” “a wrong step blindly taken”, “the missing of mark”, and it is best interpreted in the context of what Aristotle has to say about plot and “the law or probability or necessity.” In the ideal tragedy, claims Aristotle, the protagonist will mistakenly bring about his own downfall—not because he is sinful or morally weak, but because he does not know enough. The role of the hamartia in tragedy comes not from its moral status but from the inevitability of its consequences. Both Butcher and Bywater agree that hamartia is not a moral failing. This error of judgment may arise form: (i) ignorance (Oedipus), (ii) hasty – careless view(Othello) (iii) decision taken voluntarily but not deliberately(Lear, Hamlet). The error of judgement is derived form ignorance of some material fact or circumstance. Hamartia is accompanied by moral imperfections (Oedipus, Macbeth). Hence the peripeteia is really one or more self-destructive actions taken in blindness, leading to results diametrically opposed to those that were intended (often termed tragic irony), and the anagnorisis is the gaining of the essential knowledge that was previously lacking. Butcher is of the view that, “Oedipus the king – includes all three meanings of hamartia, which in English cannot be termed by a single term…. Othello is the modern example, Oedipus in the ancient, are the two most conspicuous examples of ruin wrought by characters, noble, indeed, but not without defects, acting in the dark and, as it seemed, for the best.” Hamartia is Modern plays: Hamartia is practically removed from the hero and he becomes a victim of circumstance – a mere puppet. The villain in Greek plays was destiny, now its circumstances. The hero was powerful, he struggled but at the end of the day, death is inevitable. Modern heroes, dies several deaths – passive – not the doer of the action but receiver. The concept of heroic figures in tragedy has now become practically out of date. It was appropriate to the ages when men of noble birth and eminent positions were viewed as the representative figures of society. Today, common men are representative of society and life.