Emerging Approaches in Business Model Innovation Relevant to

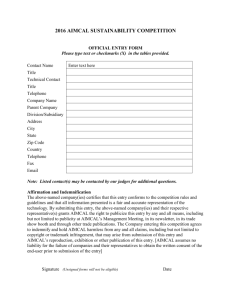

advertisement