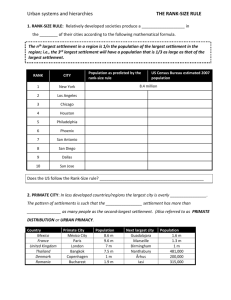

Is there an optimum city size distribution for developing countries

advertisement