Paul Krugman and Robin Wells

advertisement

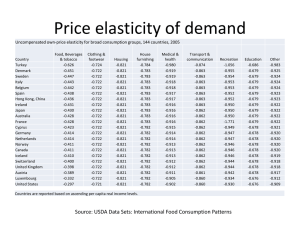

Paul Krugman and Robin Wells Microeconomics Third Edition Chapter 6 Elasticity Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers Elasticity: introduction 1. General concept: elasticity measures sensitivity, responsiveness… of one thing (the response/effect/dependent variable) to some other thing (the stimulus/cause/independent variable) e.g., elasticity of… (response) quantity demanded quantity supplied quantity demanded quantity demanded (etc. etc. etc.) with respect to… (stimulus) price price temperature rainfall often expressed as the “X-elasticity of Y” (X = stimulus, Y = response) 2. General definition: elasticity of Y (response) with respect to X (stimulus) = % change in Y % change in X The mathematics of elasticity Elasticity of Y with respect to X = % change in Y = ΔY/Y = ΔY X % change in X ΔX/X ΔX Y where ΔY = change in Y (= new value of Y – old value of Y) (and likewise for ΔX) NB: ΔY/ΔX = slope of graph of Y vs. X So, at any point on the graph, elasticity of Y with respect to X = slope of graph × ratio of Y to X Example: On a straight-line demand curve, elasticity of demand with respect to price falls as Q rises (Be careful! Remember that the graph of a demand curve has P on the vertical axis, Q on the horizontal axis!) “Elastic” demand: “Inelastic” demand: elasticity is greater than 1.0 (in absolute value) elasticity is less than 1.0 (in absolute value) Price-elasticity of demand Elasticity of demand (Q) with respect to price (P) = % change in Q = ΔQ/Q = ΔQ P % change in P ΔP/P ΔP Q (Note: elasticity of Q with respect to P is negative, BUT we usually ignore the minus sign!) As Q rises on a straight-line demand curve, ΔQ/ΔP stays the same, but P/Q falls, so elasticity of Q respect to P falls as Q rises Calculating elasticity: Simple method, “midpoint” method Example: P rises from 10 to 11, Q falls from 5 to 4 Simple method: “change” = new – old so “percent change” = (new-old)/old × 100% so ΔP = 11 – 10 = 1, ΔQ = 4 – 5 = -1 % ΔP = 1/10 = 0.10 = 10% %ΔQ = -1/5 = 0.20 = 20% …and so elasticity of Q w.r.t. P = 20 /10 = 2 But you get a different answer in reverse! e.g., P falls from 11 to 10, Q rises from 4 to 5 Then, according to the simple method, % ΔP = -1/11 = 0.0909 = 9.09% %ΔQ = 1/4 = 0.25 = 25% …and so here, elasticity of Q w.r.t. P = 25 / 0.09 = 2.75! Calculating elasticity: Simple method, “midpoint” method (continued) “midpoint” method: “change” = new – old (as before) but now define “level” as the average (midpoint) of old and new levels Example: P rises from 10 to 11, Q falls from 5 to 4 midpoint method: “change” = new – old “level” = average of old and new values = (new + old) / 2 so “percent change” = (new-old)/[(new + old)/2] × 100% so ΔP = 11 – 10 = 1, ΔQ = 4 – 5 = -1 % ΔP = 1/[(10+11)/2] %ΔQ = -1/[(4+5)/2] = 1/10.5 = 9.52% =1/4.5 = 22.22% …and so elasticity of Q w.r.t. P = 22.22 / 9.52 = 2.33 (Note that this will also work in reverse, and will give the same answer, 2.33!) Intuition tells us that demand for vaccinations is inelastic. %ΔQ = 0.1/[(10.0+9.9)/2] = 1.01% %ΔP = -1/[(21+20)/2] = -4.78% so elasticity = |1.01/-4.78| = 0.211 (remember: sign is ignored!) Figure 6.1 The Demand for Vaccinations Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers (Note that these are elasticities of demand with respect to price. They’re all negative, but for convenience (?), we ignore the minus sign.) Table 6.1 Some Estimated Price Elasticities of Demand Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers %ΔQ = 0 for any %ΔP, So here, elasticity = 0. %ΔQ = ∞ for any %ΔP, So here, elasticity = ∞. Figure 6.2 Two Extreme Cases of Price Elasticity of Demand Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers Figure 6.3 (a) Unit-Elastic Demand, Inelastic Demand, and Elastic Demand Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers Figure 6.3 (b) Unit-Elastic Demand, Inelastic Demand, and Elastic Demand Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers Figure 6.3 (c) Unit-Elastic Demand, Inelastic Demand, and Elastic Demand Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers What affects the elasticity of demand for a product? Elasticity of demand for a product is likely to be greater… • if close substitutes are available • if the market is narrowly defined (related to availability of substitutes, e.g., “Jamaica coffee” not “beverages”) • if the time horizon is long (easier to find substitutes in the long run) • if the product is a “luxury” (easier to do without) Elasticity of demand, demand and revenue Let E = % ΔQ , which involves three terms: E, % ΔQ and % ΔP. % ΔP Thus, if we know any two of them, we can calculate the third by rearranging terms. Example: if E = 1.5 and we raise price by 10%, what will happen to Q? Answer: E ×% ΔP = % ΔQ, so % ΔQ = 1.5 × 10 = 15%. Sales revenue, R, = P × Q (= price per unit times # of units sold) (Warning! Revenue R is not PROFIT, = revenue R minus total cost C!) For small % changes in P and Q, a good approximation to the resulting % change in R = % change in P + % change in Q (e.g., if P rises by 1% and Q falls by 2%, then % change in R ≈ % change in P + % change in Q = +1 – 2 = -1%.) AND, note that % ΔQ = E ×% ΔP… so that % change in R ≈ % change in P + % change in Q = %ΔP + E×% ΔP, = %ΔP [1 + E] So, when P rises, R will rise if |E| < 1, but R will fall if |E| > 1! Elasticity of demand and revenue: some intuition If |E| < 1, demand is “inelastic” (not responsive) with respect to price. So, if we raise P, then Q will not change much. We get a higher price on almost the same number of units sold. So R = P × Q will go up. If |E| < 1, it always makes sense to raise price: R will rise, and (because less Q will be produced) costs will fall. So profit = revenue – costs must rise. If |E| > 1, demand is “elastic” (responsive) with respect to price. So, if we raise P, then Q will fall by a lot. Sales drop substantially in response to the higher price. So R = P × Q will go down. Conversely, if we cut P when |E| > 1, what we lose on the higher price we will more than make up on higher sales volume (Q), so R rises. But if |E| > 1, it may not always make sense to cut price: R will rise, but it will also cost more to produce greater Q, so profit = revenue – costs might rise or fall. Figure 6.4 Total Revenue Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers Table 6.2 Price Elasticity of Demand and Total Revenue Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers Figure 6.5 The Price Elasticity of Demand Changes Along the Demand Curve Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers Some other elasticities of demand Remember that many things affect demand for a product: its own price, prices of other goods (substitutes and complements), income, temperature, advertising, … -- so, many elasticities: Elasticity of demand for a good Q with respect to income I (“income-elasticity of demand”) = %ΔQ / %ΔI positive for “normal” goods, negative for “inferior” goods Note: if income elasticity > 1, %ΔQ will be larger than the %ΔI (“luxury”?) Elasticity of demand for a good Q1 with respect to price of some other good, P2 (“cross-elasticity of demand for Q1 with respect to P2”) = %ΔQ1 / %ΔP2 Positive for substitutes (price of butter up demand for margarine up) Negative for complements (price of butter up demand for bread down) Figure 6.6 Two Extreme Cases of Price Elasticity of Supply Krugman and Wells: Microeconomics, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by Worth Publishers Some applications Farming: Increase in supply curve (big crop) with inelastic demand: P falls, but Q rises only a little, so R = PQ falls, on balance (Note: what if poor weather shifts supply curve to the left – what will happen to farmers’ revenues then?) OPEC: in short run, demand is inelastic, so P rises, Q falls only a little so on balance, R = PQ rises in long run, demand is elastic, so P rises, Q falls by a lot so on balance, R = PQ falls War on drugs (with inelastic demand) cutting supply reduces Q, but raises P: demand isn’t sensitive to P, so Q falls by only a little, so R = PQ (drug dealers’ revenue) rises cutting demand thru drug education reduces both Q and P by shifting the demand curve, so R = PQ falls So, what does Verleger think is the elasticity of demand for “petrol” (gasoline)? So, what does this tell us about the elasticity of demand for fancy dining? The higher cigarette tax will raise the price of cigarettes. Demand for cigarettes is inelastic, right? So wouldn’t the higher price raise government tax revenue? But the higher tax resulted in LOWER tax revenue! Doesn’t that mean that demand for cigarettes in NJ is elastic??? But how could that be??? PS: Gasoline tax is lower in NJ than in neighboring states. And so what would you expect here?