The Tempest - American Players Theatre

advertisement

Study guide

for the

2003 productiom of

2

July 15, 1610

... a dreadful storme and hideous

began to blow from out the

North-east, which swelling, and

roaring as it were by fits, some

houres with more violence than

others, at length did beate all

light from heaven; which like an

hell of darkness turned black

upon us, so much the more fuller

of horror.

William Strachey

On June 2 1609, the flagship Sea Adventure left the port of Plymouth with a fleet carrying

colonists to help fortify John Smith's colony in Virginia. During the fierce tempest described above, the

fleet was separated while traveling through the dreaded Bermuda Islands- the Isle of Devils. The Sea

Adventure was lost during the storm.

Almost a year after the fleet had set sail, the Sea Adventure arrived in Virginia. She had run

aground an island during the storm and had suffered severe damage. For almost a year the colonists and

crew lived on the deserted isle. The island was pleasant and provided more than enough resources to

repair the ship. The story of the Sea Adventure was regarded as a miracle and personal accounts and

pamphlets circulated throughout England.

3

Most scholars recognize the significance this event had on a certain playwright and in 1613

Shakespeare wrote The Tempest.

4

'Tis time I

farther ... "

should

info~

the

A storm strikes a ship carrying Alonso, Ferdinand,

;>

Sebastian, Antonio, Gonzalo, Stefano, and Trinculo, who are en

route to Italy after coming from the wedding of Alonso's

daughter. The royal party and the mariners begin to fear for their

lives. Lightning cracks, and the mariners cry that the ship has

been hit. Everyone prepares to sink.

The next scene begins much more quietly. Miranda and

Prospero stand on the shore of their island, looking out to sea at

the recent shipwreck. Miranda asks her father to do anything he

can to help the poor souls in the ship. Prospero assures her that

everything is all right and then informs her that it is time she

learned more about herself and her past. He reveals to her that

he orchestrated the shipwreck and tells her the lengthy story of

her past- that Prospera was the Duke of Milan until his brother

Antonio, conspiring with Alonso, the King of Naples, usurped his position. With the help of Gonzalo, Prospero was

able to escape with his daughter and with the books that are the source of his magic and power. Prospero and his

daughter arrived on the island where they are now and have been for twelve years. Only now, Prospero says, has

Fortune at last sent his enemies his way, and he has raised the tempest in order to make things right with them

once and for all.

After telling this story, Prospera charms Miranda to sleep and then calls forth his familiar spirit Ariel, his chief

magical agent. He then makes sure that everyone got safely to the island, though they are now separated from

each other into small groups.

Miranda awakens from her sleep, and she and Prospero

go to visit Caliban, Prospero's servant and the son of the dead

witch Sycorax. Caliban curses Prospero, and Prospero and

Miranda berate him for being ungrateful for what they have

given and taught him. Prospero sends Caliban to fetch

firewood. Ariel, invisible, enters playing music and leading in

the awed Ferdinand. Miranda and Ferdinand are immediately

smitten with each other. He is the only man Miranda has ever

seen, besides Caliban and her father. Prospero is happy to

see that his plan for his daughter's future marriage is working,

but decides that he must upset things temporarily in order to

prevent their relationship from developing too quickly.

On another part of the island, Alonso, Sebastian, Antonio,

and Gonzalo worry about the fate of Ferdinand. Gonzalo tries

to maintain high spirits by talking of the beauty of the island,

but his remarks are undercut by the sarcastic sourness of Antonio and Sebastian. Ariel appears, invisible, and

plays music that puts all but Sebastian and Antonio to sleep. These two then begin to discuss the possible

advantages of killing their sleeping companions. Antonio persuades Sebastian that the latter will become ruler of

Naples if they kill Alonso and the two are about to stab the sleeping men when Ariel causes Gonzalo to wake with a

shout. Everyone wakes up, and Antonio and Sebastian concoct a ridiculous story about having drawn their swords

to protect the king from lions. Ariel goes back to Prospero while Alonso and his party continue to search for

Ferdinand.

Caliban, meanwhile, is hauling wood for Prospero when he thinks a spirit sent by Prospero is come to

torment him. He lies down and hides under his cloak. A storm is brewing, and Trinculo, enters and crawls under the

cloak to protect him from the lightening. Stefano, drunk and singing, comes along and stumbles upon the bizarre

spectacle of Caliban and Trinculo huddled under the cloak. Stefano decides that this monster requires liquor and

attempts to get Caliban to drink. Trinculo recognizes his friend Stefano and calls out to him. Soon the three are

sitting up together and drinking. Caliban quickly becomes an enthusiastic drinker, and begins to sing.

5

Prospero puts Ferdinand to work hauling wood. Ferdinand finds his labor pleasant because it is for Miranda's

sake and she tells him to take a break. The two flirt with one another. Miranda proposes marriage, and Ferdinand

accepts. Prospero has been on stage most of the time, unseen, and he is pleased with this development.

Stefano, Trinculo, and Caliban are now drunk and raucous. Caliban proposes that they kill Prospera, take his

daughter, and set Stefano up as king of the island. Stefano thinks this a good plan, and the three prepare to set off

to find Prospera.

Alonso, Gonzalo, Sebastian, and Antonio grow weary from traveling and pause to rest. Antonio and

Sebastian secretly plot to take advantage of Alonso and Gonzalo's exhaustion, deciding to kill them in the evening.

A magical banquet is then brought out by strangely shaped spirits. As the men prepare to eat, Ariel appears like a

harpy and accuses the men of supplanting Prospero and says that it was for this sin that Alonso's son, Ferdinand,

has been taken. He vanishes, leaving Alonso, Antonio and Sebastian mad and wracked with guilt.

Prospera now softens toward Ferdinand and welcomes him

into his family as the soon-to-be-husband of Miranda. He sternly

reminds Ferdinand, however, that Miranda's "virgin-knot" (IV.i.15)

is not to be broken until the wedding has been officially

solemnized. Prospero then asks Ariel to call forth some spirits to

perform a masque for Ferdinand and Miranda. The spirits assume

the shapes of Ceres, Juno, and Iris and perform a short masque

celebrating the rites of marriage and the bounty of the earth.

Prospero suddenly remembers that he still must stop the plot

against his life. He sends Ferdinand and Miranda and the spirits

away. Ariel and Prospero then set a trap by hanging beautiful

clothing in Prospero's cell. Stefano, Trinculo, and Caliban enter

looking for Prospero and, finding the beautiful clothing, decide to

steal it. They are immediately set upon by a pack of spirits in the

shape of dogs and hounds, driven on by Prospero and Ariel.

Prospero uses Ariel to bring Alonso and the others before him and confronts

Alonso, Antonio, and Sebastian with their treachery, but tells them that he forgives them.

Alonso tells him of having lost Ferdinand in the tempest and Prospero says that he

recently lost his own daughter. Clarifying his meaning, he draws aside a curtain to reveal

Ferdinand and Miranda playing chess. Alonso and his companions are amazed at the

miracle of Ferdinand's survival, and Miranda is amazed at the sight of people unlike any

she has seen before. Ferdinand tells his father of his marriage.

Ariel returns with the Boatswain and mariners. The Boatswain tells a story of

having been awakened from a sleep that had apparently lasted since the tempest. At

Prospero's bidding, Ariel releases Cali ban, Trinculo and Stefano, who then enter wearing

their stolen clothing. Prospero and Alonso command them to return it and to clean up

Prospero's cell. Prospero invites Alonso and the others to stay for the night so that he

can tell them the tale of his life in the past twelve years. After this, the group plans to

return to Italy. Prospero, restored to his dukedom, will retire to Milan. Prospero gives Ariel one final task-s-to make

sure the seas are calm for the return voyage-before setting him free. Finally, Prospera delivers an epilogue to the

audience, asking them to forgive him his wrongs and set him free by applauding.

6

~What

have we here? a man or a

· h ?.... II

f l.S

Prospero - Father of Miranda. Twelve years before the events of the play, Prospero was the duke of Milan. His

brother, Antonio, in concert with Sebastion and Alonso, king of Naples, usurped him, forcing him to flee in a boat

with his daughter. The honest lord Gonzalo aided Prospero in his escape. Prospero has spent his twelve years on

the island refining the magic that gives him the power he needs to punish and forgive his enemies.

Miranda - The daughter of Prospero, Miranda was brought to the island at an early age and has never seen any

men other than her father and Caliban. Because she has been sealed off from the world for so long, Miranda's

perceptions of other people tend to be natve and non-judgmental. She is compassionate, generous, and loyal to

her father.

Ariel - Prospero's spirit helper. Rescued by Prospero from a long imprisonment at the hands of the witch Sycorax,

Ariel is Prospero's servant until Prospero decides to release him. It is Ariel's pity for the tormented court that allows

Prospero to see his own hardened heart.

Caliban - Another of Prospera's servants. Caliban, the son of the now-deceased witch Sycorax, acquainted

Prospero with the island when Prospero arrived. Caliban believes that the island rightfully belongs to him and has

been stolen by Prospero. His speech and behavior is sometimes coarse and brutal, as in his drunken scenes with

Stefano and Trinculo (lIl.ii, IV.i), and sometimes eloquent and sensitive, as in his rebukes of Prospero in Act I,

scene ii, and in his description of the eerie beauty of the island in Act III, scene ii (1II.ii.130-138). Much debate has

been had on exactly what he looks like.

Ferdinand - Son and heir of Alonso. Ferdinand seems in some ways to be as pure and narve as Miranda. He falls

in love with her upon first sight and happily submits to servitude in order to win her father's approval.

Alonso - King of Naples and father of Ferdinand. Alonso aided Antonio in unseating Prospera as Duke of Milan

twelve years before. As he appears in the play, however, he is acutely aware of the consequences of all his actions

and after the magical banquet, he regrets his role in the usurping of Prospero.

Antonio - Prospero's brother. Antonio quickly demonstrates that he is power-hungry and foolish. In Act II, scene i,

he persuades Sebastian to kill the sleeping Alonso. When Prospera forgives his brother it is unclear as to whether

Antonio actually excepts his forgiveness.

Sebastian - Alonso's brother. He is persuaded to kill his brother in Act II, scene i. He was part of the plot of the

overthrow of Prospero.

Gonzalo - An old, honest lord, Gonzalo helped Prospero and Miranda to escape after Antonio usurped Prospero's

title. Gonzalo's speeches provide an important commentary on the events of the play, as he remarks on the beauty

of the island when the stranded party first lands, then on the desperation of Alonso after the magic banquet, and on

the miracle of the reconciliation in Act V, scene i.

Trinculo and Stefano - Trinculo, a jester, and Stefano, a drunken butler, are two minor members of the

shipwrecked party. They provide a comic foil to the other, more powerful pairs of Prospero and Alonso and Antonio

and Sebastian. Their drunken boasting and petty greed reflect and deflate the quarrels and power struggles of

Prospero and the other noblemen.

7

"Wit shall not go unrewarded while

I am king of this coun t ry... "

Themes

Themes are the fundamental and often universal ideas explored in a literary work.

The Illusion of Justice - The Tempest tells a fairly straightforward story involving an unjust act, the usurpation of

Prospero's throne by his brother, and Prospero's quest to re-establish justice by restoring himself to power.

However, the idea of justice that the play works toward seems highly subjective, since this idea is the view of one

character who controls the fate of all the other characters. Though Prospero represents himself as a victim of

injustice working to right the wrongs that have been done to him, Prospero's idea of justice and injustice is

somewhat hypocritical-for example, though he is furious with his brother for taking his power, he has no qualms

about enslaving Ariel and Caliban in order to achieve his ends and he never tells Alonso about the plot on his life by

his brother Sebastion. At many moments throughout the play, Prospero's sense of justice seems extremely onesided, mainly involving what is good for Prospero. Moreover, because the play offers no notion of higher order or

justice to supercede Prospero's interpretation of events, the play seems somewhat morally ambiguous.

As the play progresses, however, it begins to become more and more involved with the idea of creativity and

art, and Prospero's role begins to mirror more explicitly the role of an author creating a story around him. With this

metaphor in mind, and especially if we accept Prospero as a surrogate for Shakespeare himself, Prospero's sense

of justice begins to seem, if not perfect, at least sympathetic. Moreover, the means he uses to achieve his idea of

justice mirror the machinations of the artist, who also seeks to enable others to see his view of the world.

Playwrights arrange their stories in such a way their own idea of justice is imposed upon events. In The Tempest,

the author is in the play, and the fact that he establishes his idea of justice and creates a happy ending for all the

characters becomes a cause, not for criticism, but for celebration. Using magic and tricks that echo the special

effects and spectacles of the theater, Prospero gradually persuades the other characters and the audience of the

rightness of his case. As he does so, the arnbiqultles surrounding his methods slowly resolve themselves. Prospero

forgives his enemies, releases his slaves, and relinquishes his magic power, so that, at the end of the play, he is

only an old man whose work has been responsible for all the audience's pleasure. In this way, the establishment of

Prospero's idea of justice becomes less a commentary on justice in life than on the nature of morality in art. Happy

endings are possible, Shakespeare seems to say, because the creativity of artists can create them, even if the

moral values that establish the happy ending originate from nowhere but the imagination of the artist.

The Difficulty of Distinguishing "Men" from "Monsters" - Upon seeing Ferdinand for the first time, Miranda

says that he is "the third man that e'er I saw" (l.ii.449). The other two are, presumably, Prospero and Caliban. In

their first conversation with Caliban, however, Miranda and Prospero say very little that shows they consider him to

be human. Miranda reminds Caliban that before she taught him language, he gabbled "like / A thing most brutish"

(l.ii.59-60) and Prospero says that he gave Caliban "human care" (l.ii.349), implying that this was something

Caliban Ultimately did not deserve. Caliban's exact nature continues to be slightly ambiguous later. In Act IV, scene

l, reminded of Caliban's plot, Prospero refers to him as a "devil, a born devil, on whose nature / Nurture can never

stick" (IV.i.188-189). Miranda and Prospero both have contradictory views of Caliban's humanity. On the one hand,

they think that their education of him has lifted him from his originally brutish status. On the other hand, they seem

to see him as inherently brutish. His devilish nature can never be overcome by nurture, according to Prospero;

Miranda expresses a similar sentiment in Act I, scene ii: "thy vile race, / Though thou didst learn, had that in't which

good natures / Could not abide to be with" (l.ii.361-363). The inhuman part of Caliban drives out the human part,

the "good nature," that is imposed on him.

Caliban claims that he was kind to Prospera, and that Prospero repaid that kindness by imprisoning him (see

l.ii.347). In contrast, Prospero claims that he stopped being kind to Caliban once Caliban had tried to rape Miranda

(l.ii.347-351) to which Caliban responds saying "would it had been done". How audience decides to view Cali ban

(as inherently brutish, or as made brutish by oppression) the play leaves to its audience. Caliban balances all of his

eloquent speeches, such as his curses in Act I, scene ii and his speech about the isle's "noises" in Act III, scene il,

with the most degrading kind of drunken, servile behavior. But Trinculo's speech upon first seeing Caliban (11.ii.1838), the longest speech in the play, reproaches too harsh a view of Caliban and blurs the distinction between men

and monsters. In England, which he visited once, Trinculo says, Caliban could be shown off for money: "There

8

would this monster make a man. Any strange beast there makes a man. When they will not give a doit to relieve a

lame beggar, they will lay out ten to see a dead Indian" (1I.ii.28-31). What seems most monstrous in these

sentences is not the "dead Indian," or "any strange beast," but the cruel voyeurism of those who capture and gape

at them.

The Allure of Ruling a Colony - The nearly uninhabited island presents the sense of infinite possibility to almost

everyone who lands there. Prospera has found it, in its isolation, an ideal place to school his daughter. Sycorax,

Caliban's mother, worked her magic there after she had been exiled from Algeria. Caliban, once alone on the

island, now Prospero's slave, laments that he was once his own king (l.ii.344-345). As he attempts to comfort

Alonso, Gonzalo imagines a utopian society on the island, over which he would be the ruler (1I.i.148-156). In Act III,

scene ii, Caliban suggests that Stefano kill Prospero, and Stefano immediately begins to envision his own reign:

"Monster, I will kill this man. His daughter and I will be King and Queen-save our graces!-and Trinculo and

thyself shall be my viceroys" (III. ii.101-1 03). Stefano particularly looks forward to taking advantage of the spirits

that make "noises" on the isle; they will provide music for his kingdom for free. All of these characters envision the

island as a space of freedom and unrealized potential.

The tone of the play, however, toward the hopes of the would-be colonizers is vexed at best. Gonzalo's

utopian vision in Act II, scene i is undercut by a sharp retort from the usually foolish Sebastian and Antonio, When

Gonzalo says that there would be no commerce or work or "sovereignty" in his society, Sebastian replies, "yet he

would be king on't," and Antonio adds, "The latter end of his commonwealth forgets the beginning" (11.i.156-157).

Gonzalo's fantasy thus involves him ruling the island while seeming not to rule it, and in this he becomes a kind of

parody of Prospera.

While there are many representatives of the colonial impulse in the play, the colonized have only one

representative: Caliban. We might develop sympathy for him at first, when Prospero seeks him out merely to abuse

him, and when we see him tormented by spirits. However, this sympathy is made more difficult by his willingness to

abase himself before Stefano in Act II, scene ii. Even as Caliban plots to kill one colonial master (Prospero) in Act

III, scene ii, he sets up another (Stefano). The urge to rule and the urge to be ruled seem inextricably intertwined.

Motifs

Motifs are recurring structures, contrasts, or literary devices that can help to develop and inform the text's

major themes.

Masters and Servants - Nearly every scene in the play either explicitly or implicitly portrays a relationship between

a figure that possesses power and a figure that is SUbject to that power. The play explores the master-servant

dynamic most harshly in cases in which the harmony of the relationship is threatened or disrupted, as by the

rebellion of a servant or the ineptitude of a master. For instance, in the opening scene, the "servant" (the

Boatswain) is dismissive and angry toward his "masters" (the noblemen), whose ineptitude threatens to lead to a

shipwreck in the storm. From then on, master-servant relationships, such as the following, dominate the play:

Prospera and Caliban; Prospero and Ariel; Alonso and his nobles; the nobles and Gonzalo; Stefano, Trinculo, and

Caliban; and so forth. The play explores the psychological and social dynamics of power relationships from a

number of contrasting angles, such as the generally positive relationship between Prospero and Ariel, the generally

negative relationship between Prospera and Caliban, and the treachery attending on Alonso's relationship to his

nobles.

Water and Drowning - The play is awash with references to water. The Mariners enter "wet" at in Act I, scene i,

and Caliban, Stefano, and Trinculo enter "all wet," after being led by Ariel into a swampy lake (IV.i.193). Miranda's

fear for the lives of the sailors in the "wild waters" (l.ii.2) causes her to weep. Alonso, believing his son dead

because of his own actions against Prospera, decides in Act III, scene iii to drown himself. His language is echoed

by Prospero in Act V, scene i when the magician promises that, once he has reconciled with his enemies, "deeper

than did ever plummet sound / I'll drown my book" (V.i.56-57).

These are only a few of the references to water in the play. Occasionally, the references to water are used to

compare characters. For example, the echo of Alonso's desire to drown himself in Prospero's promise to drown his

book calls attention to the similarity of the sacrifices each man must make. Alonso must be willing to give up his life

in order to become truly penitent and to be forgiven for his treachery against Prospero. Similarly, in order to rejoin

the world he has been driven from, Prospero must be willing to give up his magic and his power.

Perhaps the most important overall effect of this water motif is to heighten the symbolic importance of the

9

tempest itself. It is as though the water from that storm runs through the language and action of the entire playjust as the tempest itself literally and crucially affects the lives and actions of all the characters.

Mysterious Noises - The isle is indeed, as Caliban says, "full of noises" (1II.ii.130). The play begins with a

"tempestuous noise of thunder and lightning" (I.i.1, stage direction), and the splitting of the ship is signaled in part

by "a confused noise within" (1.i.54, stage direction). Much of the noise of the play is musical, and much of the

music is Ariel's. Ferdinand is led to Miranda by Ariel's music. Ariel's music also wakes Gonzalo just as Antonio and

Sebastian are about to kill Alonso in Act II, scene i. Moreover, the magical banquet of Act III, scene iii is laid out to

the tune of "Solemn and strange music" (1II.iii.18, stage direction), and Juno and Ceres sing in the wedding masque

(IV.i.106-117).

The noises, sounds, and music of the play are made most significant by Caliban's speech about the noises

of the island at III.ii.130-138. Shakespeare shows Caliban in the thrall of a magic that the theater audience also

experiences as the illusion of thunder, rain, invisibility. The action of The Tempest is very simple. What gives the

play most of its hypnotic, magical atmosphere is the series of dreamlike events it stages, such as the tempest, the

magical banquet, and the wedding masque. Accompanied by music, these present a feast for the eye and the ear

and convince us of the magical glory of Prospero's enchanted isle.

10

"And deeper than did ever plummet

sound I'll drown my book"

1. Analyze Caliban's "the isle is full of noises" speech (1I1.ii.130-138). What makes it such a compelling and

beautiful passage? What is its relation to Caliban's other speeches, and to his character in general? What effect

does this speech have on our perception of Caliban's character? Why does Shakespeare give these lines to

Caliban rather than, say, Ariel or Miranda?

2. What is the nature of Prospero and Miranda's relationship? Discuss moments where Miranda seems to be

entirely dependent on her father and moments where she seems independent. How does Miranda's character

change over the course of the play?

3. Discuss Ferdinand's character. What is the nature of his love for Miranda? Is he a likable character? What is

the nature of his relationship to other characters?

4.

Who is forgiven at the end of the play and actually excepts the forgiveness? Previous productions have had

Antonio walk away from Prospero's forgiveness. If you were to direct the last scene, how would you stage the

forgiveness and who would except it? Use the text to back-up your ideas.

5.

Virtually every character in the play expresses some desire to be lord of the island. Discuss two or three of

these characters. How does each envision the island's potential? How does each envision his own rule? Who

comes closest to matching your own vision of the ideal rule?

6.

Analyze the tempest scene in Act I, scene i. How does Shakespeare use the very limited resources of his bare

stage to create a sense of realism? How does the APT Production grapple with the opening? Previous productions

have had Prospera standing center holding a little wooden boat while the storm sounds and dialogue are heard

from off stage. Other productions have had the court and crew enter in a tight boat-like formation while crossing the

stage in a rhythmically swaying motion. When the boat splits the court and crew disperse chaotically. If you were to

direct the opening tempest scene, how would you approach it?

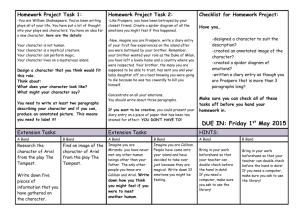

7. "Have we devils here?" What does Caliban look like? Find all the references to Caliban's look and behaviour"..a man or fish?" Armed with these descriptions design or describe your own costume.

II

T

..

~,

""'<-

{

.'·· ;>v . •. •. .

n··

A great deal has been made of the fact that Forbidden Planet is essentially Shakespeare's The Tempest

(1611) in an sf setting. It is this which transforms Forbidden Planet into far more than a mere pulp

reading. The Tempest is set on a Mediterranean island where the magician Prospero lives in exile from

Milan, along with his daughter Miranda, the tamed spirit Ariel and the bestial Caliban, original lord of the

island. The idyll is upset by the arrival of various shipwrecked Milanese dignitaries, one of whom falls in

love with Miranda. Forbidden Planet transplants the play and finds science-fictional equivalents for the

Shakespearean characters - the magician Prospero becomes the archaeologist Morbius, Miranda becomes

Altaira, Caliban becomes the Id monster, the Milanese dignitaries become the Earthmen and in a

transposition that it is unlikely that Shakespeare in his wildest dreams could ever have imagined the

ethereal Ariel is now played by a robot. And what is even more striking is the subtext put on the play Caliban is transformed from the original inhabitant of the island into an amorphous 'monster from the id'

made manifest, a direct nod to the era's fad for Freudian psychology. But there's also the fact that

Morbius/Prospero, despite being given an ostensible reason about wanting to protect the Krell discoveries,

can be clearly read as having an unstated jealousy over the sexual attentions forced on his daughter by the

earthmen. It's quite an incredible underscoring to a film, especially to find when one comes to this as a

film whose legend lies in fandom more for its successful display of pulp content.

Copyright Richard Scheib 2002

A r

.

1

e

12

PROSPERA'S

ROUGH MAGIC

"IT'S IMPOSSIBLE to believe this wasn't written for a woman," director Emily Mann says of The Tempest. "It fits

like a glove."

Meet Prospera, single mom and linchpin of what many have called Shakespeare's most emotionally mature work.

When Tony-winning actress Blair Brown assumed the role last February in the production Mann directed at the McCarter

Theatre Center in Princeton, N.J., she was not the first woman to do so. British actress Valerie Braddell was an acclaimed

Prospero for the Actors Touring Company in 1981, for example, and interest in the approach has spiked since 2000, when

Vanessa Redgrave played the role at London's Globe Theatre. (Like Braddell, Red grave portrayed Prospero as a man.) . Since

then, three major U.S. theatres have each changed Prospero to Prospera, starting with an Oregon Shakespeare Festival Tempest

starring Demetra Pittman in 2001.

Some months before the McCarter production opened, Terry Bamberger played the part in a San Francisco

Shakespeare Festival version that toured schools in 2002.

Why the surge in Prosperas? Several actresses are frustrated by the dearth of meaty Shakespearean roles for what Pittman calls

"women in their middle years." Of all the major male parts, Prospero is arguably Shakespeare's most "sexless, " if for no other

reason than that the play's isolated setting doesn't lend itself to romantic couplings. And the character's gradual transition from

vengeance to mercy has special significance to many of the female actors and directors involved.

Prospero is also one of Shakespeare's more "hands-on dads," as Brown puts it, a quality that lends itself particularly

well to the gender swap. Pittman, her Oregon counterpart, agrees: "Prospero is much more of a caregiver- almost too much, to

a degree. And that's what we often associate with mother-daughter relationships. "

While the Prospera-Miranda dynamic grew more tender in both the Oregon and the McCarter productions, Prospera's

attitude toward the island's other two inhabitants-Caliban and Ariel- - became harsher. Brown and Pittman say they both

played Prospera as more of what Pittman calls "an oppressor of Caliban and Ariel." In particular, the relationship between

Prospero and Caliban, who lived as a free man on the island until being enslaved after attempting to violate - Miranda,

becomes far more complex with the added layer of sexual tension. Phrases such as Cal iban's "When thou cam'st first / Thou

strok'st me and made much of me," and his subsequent rage toward his master, take on a very different tone when Prospero

becomes Prospera. "There's a whole 'back story' implicit, or at least possible, in the case of Prospera and Caliban" says Diana

Henderson, an associate professor of literature at M.l. T. who has written extensively about Shakespeare.

The Oregon and McCarter productions deviated from the typical portrayal of Cali ban as a sort of monster or" missing

link, " turning him instead into a more conventionally handsome personage. Though the relationship between the two was left

somewhat ambiguous in Oregon, according to the artists involved, McCarter director Manu emphasized the chemistry between

Brown and her Caliban (Ian Kahn).

Discussing their Tempests, director Manu and actors Brown and Pittman all stressed the importance of Prospera's shift

toward an all-embracing state of mercy, embodied in the line "The rarer action / Is in virtue than in vengeance. " During

rehearsals, said Mann, who is the McCarter's artistic director, she drew upon her firsthand exposure to the controversial Truth

and Reconciliation Commission hearings in post-apartheid South Africa. This exposure was instrumental in illuminating what

she calls "the enormous burden of forgiveness" on Prospera's part. "

Almost all of Shakespeare's plays deal with: How does one rule well? How does one rule better?" she says. "Instead of

revenge, one could make the choice to forgive-and forgiveness is not always an easy thing. " Notable among the dynamics in

her staging of the finale were Prospera's lingering, fraught glance at the newly freed Caliban and the image ofa chastened

Antonio-Prospero's brother and usurper as duke-silently walking away from Prosperas outstretched hand. As he refuses

absolution, we were reminded that being forgiven is as much a choice as forgiving.

Mann and the two actresses all believe the potential exists for many more Prospera productions. Brown, who has

lobbied in the past for all- female productions of Art and Shakespeare's R&J, was ecstatic about the creation of a substantial

Shakespearean role like Prospera. "Most female parts in the classical repertory, good as they may be, are almost entirely about

love-love toward a man, love toward children," she says. " And I'm not denigrating those parts, but there are limits." AT

Eric Grode is a 2002-03 American Theatre Affiliated Writer with support from a grant by the Jerome Foundation.

13

"Tend to the Master's whistle ... "

The following guide is provided by Joseph R. Scotese through the Folger Shakespeare

Lesson Plan Series.

Today students will be introduced to The Tempest. They will act out the opening

shipwreck scene, or watch and direct others doing it. By doing this activity, students

will use the text to understand the plot, see that what seemed daunting is not quite so

difficult, and have fun and embarrass themselves in the name of Shakespeare. This

activity will take one class period.

What to Do:

1. Preparation (reading the night before)

Students will have read the opening shipwreck scene before coming in to class today.

Expect (didn't they teach you never to have any "prejudgments" about students?)

students to grumble that they didn't "get it."

2. Getting Started

Before you can say "lack Robinson" rush the students out to some public place that

has lots of movable objects like desks and chairs. Lunchrooms and study halls are

ideal. Break the students up into groups of seven to ten.

3. Students on Their Feet and Rehearsing the Scene

Give the students scripts of the scene from which you've removed any stage

directions, line numbers, or glosses. Have the students divide the parts for the opening

scene. Make sure they include all the sailors, crashing waves, etc. Then they are first

to pantomime the entire scene, so they must plan and act out every important action

that occurs in the scene. Give the groups a good ten minutes to do this.

4. The Finished Product

Have all the groups present their pantomimes. After each scene ask students (the ones

not performing) to quietly write down what the performing group did well and what

they might have missed. When all of the scenes have been performed, have the

students read their comments.

5. Directing the Spoken Scene

Randomly choose one of the groups and have the students perform the scene complete

with words. Give them five minutes or so to prepare and tell them to make sure they

include the students suggestions for all of the scenes. If time permits, allow the other

students to make comments that direct the group's performance.

14

What you'll Need:

a lunchroom; kids who aren't afraid of getting a wee bit embarrassed; a copy of the

shipwreck scene that has had all of the stage directions, line numbers, and glosses

taken out

How did it Go:

You can check how the students did based on their pantomimes, their comments, their

final production, and the inclusion of any comments such as "that wasn't as hard as it

seemed last night ..."

More specifically, after you are finished, ask the students to contrast their

understanding of the scene before and after the exercise. (You may wish to have them

write down their understanding of the scene before you begin, then have them write it

again after they finish.)

Carol Ja2o'S Four Boxes

I've adapted her technique listed in the book, so that Elementary and Middle school students working on

Shakespeare can use it as well.

1. Begin with a large sheet of white paper and have the class fold it into fours.

2.

Based on in-class reading or discussion of a theme or plot within the play (revenge, Prospero frees Ariel,

Proteus lies to the Duke, friendship, etc.), have the students, in the FIRST BOX, draw a picture of a

powerful image they had during the reading or discussion. You may assign the entire class one theme or

plot or you could have the students choose the image that spoke strongest to them. This image mayor

may not directly relate to the example within the play- the student may chose to represent something from

their life or the play, whichever is stronger. Not everyone's an artist- and artistic talent is not required- just a

sincere effort to get at what's in their mind's eye. Encourage them to draw a metaphor of those thoughts,

feelings, or themes.

3.

In the SECOND BOX, put that picture into words. Ariel is a cloud that wears cinderblock boots. She flies

around and stuff, but she's still stuck in the mud and can't blow away like thw other clouds.

4.

In the THIRD BOX, have the students pretend that they are the teacher. Have them write down what or

how they would teach the theme or plot discussed.

5.

In the FOURTH BOX, have them write a poem, create a word collage, write a quote from the play, a piece

of a song, or in any other way that suited them to respond to the scene or theme drawn.

It can take a single class period or be stretched out over two or three. It provides the option of allowing students to

explore themes or scenes that they found powerful in the play and they examine this moment from various

perspectives.

15

Scatterbrained Soliloquies

th

rz"

Can be used with 4 graders depending on the passage.

The following is provided by Russ Bartlett through the Folger Shakespeare Lesson Plan Series.

Small groups of students will look at a famous soliloquy or monologue whose lines have been written on separate

pieces of paper and then scrambled. As the students work to reassemble their scrambled passages, they will

become more aware of sentence structure, meter, meaning, characterization, and vocabulary.

You will need one scrambled soliloquy or monologue packet for each small group; each packet must be printed on

different colored paper.

This lesson will take one to two class periods.

1. Divide the class into small groups of three to five students, and assign each group a color. Explain that

they will be looking at a passage from the current play, trying to make sense of its meaning. First (my

favorite part)...

2. Take all of your scrambled packets, mix them together for a rainbow effect, and throw them up into the

air, in two or three dramatic tosses. Once the pieces of paper settle to the floor ...

3. Assure the students that you have not gone crazy. Remind each group of its assigned color, and ask

each group to pick up all the pieces of that particular color. Each group should end up with the same

number of pieces. Briefly set up the context of the speech and explain that now they must...

4. Put the speech in order, laying out the papers on their desktops or on the floor. (No peeking in their

books is allowed!) How can they accomplish this task, they wonder, not knowing many of the words or

expressions? Easy, you tell them ...

5. Create a word bank on the blackboard, noting unfamiliar words, phrases, and concepts. Ask a few

probing questions that might help them figure out the meanings for themselves. If students get stuck on

a particular word or phrase, have the students refer to dictionaries or Shakespearean glossaries.

Armed with this new knowledge, they can...

6. Put the various pieces of paper in order and be prepared to explain/defend all of the choices made.

Why did you put a certain line where you did? What clues led to your group's final order? When the

.

groups are finished...

7. Pick one group to read its assembled passage aloud, while other groups check it against their finished

sequences. After one group has had its chance ...

8. Check the order of the lines in each group's soliloquy, asking each group to explain its choices. List on

the board the criteria used to determine line order. Compare and contrast the different versions. When

the entire class has decided on the best, most accurate, plausible or even elegant version ...

9. Tack the pieces in order on a bulletin board, or punch holes in them and string them together for a

hanging display. The possibilities are endless. Inform the students that they may now...

10. Consult their texts to check the order of the speech.

Were the students able to reassemble the soliloquy in logical and meaningful ways? Did the explanations offered

by group members reflect attentiveness to meaning, sound and rhyme, characterization, compatibility with prior

events occurring in the play, etc.?

"Scatterbrained Soliloquy" packets: You will need to divide up the speech into at least ten sections, writing in large

letters on white typing paper. Preserve the poetry in your transcribing (don't turn it into prose as you copy it) but feel

free to create a break in mid-line or mid-sentence. When you have broken up the passage into at least ten sections,

copy the sets in different colors or number them per group, as many different colors or numbers as there are

groups participating. The prep time for this lesson is a bit long, but if you collect the copies from your students at

the end of the exercise, you can use the packets again next year.

16

"Gabble like a thing

"

A fool's paradise.--Romeo and Juliet.

A foregone conclusion.--Othello.

A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!--Richard 11/

Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him.--Hamlet.

A little pot and soon hot.-- The Taming of the Shrew

All the world's a stage.--As You Like It

All's well that ends well--AlI's Well That Ends Well

As ... luck would have it.-- The Merl}' Wives of Windsor.

Beware the ides of March--Julius Caesar.

Blow, blow, thou winter wind.--As You Like It

Brave new world.-- The Tempest

Brevity is the soul of wit.--Hamlet

Cold comfort.--King John

Come full circle--King Lear

Come what may.--Macbeth

Conscience does make cowards of us all.--Hamlet

Cowards die many times before their deaths.--Julius Caesar

Crack of doom.--Macbeth

Death by inches--Coriolanus

Dish fit for the gods.--Julius Caesar

Dog will have its day--Hamlet

Done to death.--Much Ado About Nothing

Double, double, toil and trouble; fire burn, and cauldron bubble.-Macbeth

Eaten me out of house and home.--Henl}' IV

Elbow room.--King John

Et tu, Brute! [Latin: And you, Brutus!]--Julius Caesar

Every inch a king.--King Lear

Fatal vision.--Macbeth

Flaming youth.--Hamlet

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears.--Julius Caesar

Give the devil his due.--Henl}' IV

Green-eyed monster.--Othello

Halcyon days.--Henl}' VI

Hearts of gold--Henl}' VI Part I

Her infinite variety.--Antony and Cleopatra

Hold a candle to.-- The Merchant of Venice

I am fortune's fool.--Romeo and Juliet

I cannot tell what the dickens his name is.--Merl}' Wives of Windsor

I have not slept one wink.--Cymbeline

In my mind's eye.--Hamlet

It's a wise father that knows his own child.-- The Merchant of Venice

It smells to heaven.--Hamlet

It was Greek to me.--Julius Caesar

Kill ... with kindness.-- The Taming of the Shrew

Lend me your ears.--Julius Caesar

Let slip the dogs of war.--Julius Caesar

Lord, what fools these mortals be!--A Midsummer Night's Dream

Love is blind.-- The Merchant of Venice

Lov'd not wisely, but too well.--Othello

Merry as the day is long.--Much Ado About Nothing

More sinned against than sinning.--King Lear

My own flesh and blood.-- The Merchant of Venice

My salad days, when I was green in judgement.--Antony and

Cleopatra

Neither a borrower nor a lender be.--Hamlet

Neither rhyme nor reason.--As You Like It

Now is the winter of our discontent.--Richard 1/1

Once more unto the breach.--Henl}' V

One fell swoop--Macbeth

Out, damned spot!--Macbeth

Out of the question.--Love's Labour's Lost

Paint the lily.--King John

Parting is such sweet sorrow.--Romeo and Juliet

Play fast and loose.--Love's Labour's Lost

Primrose path.--Hamlet

Put out the Iight.--Othello

Seamy Side--Othello.

Short and the Long of It--Merl}' Wives of Windsor

Smooth runs the water where the brook is deep.--Henl}' VI, Part 1/

Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.--Hamlet

Something wicked this way comes.--Macbeth

Something in the wind.-- The Comedy of Errors

Sorry sight.--Macbeth

Spotless reputation.--Richard 11/

Star-cross'd lovers--Romeo and Juliet

Strange bedfellows.--The Tempest

Sweets to the sweet--Hamlet

What's in a name?--Romeo and Juliet

The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose.--The Merchant of Venice

The first thing we do, let's kill all the lawyers.--Henl}' VI

The lady doth protest too much.--Hamlet

The play's the thing.--Hamlet

The quality of mercy is not strained.-- The Merchant of Venice

The short and the long of it.-- The Merl}' Wives of Windsor

The working day world.--As You Like It

The world's mine oyster.-- The Merry Wives of Windsor

There is a tide in the affairs of men.--Julius Caesar

They sayan old man is twice a child.--Hamlet

This was the noblest Roman of them all.--Julius Caesar

Though this be madness, yet there is method in't.--Hamlet

Throw cold water on it.-- The Merl}' Wives of Windsor

'Tis neither here nor there.--Othello

To be, or not to be: that is the question.--Hamlet

Too much of a good thing.--As You Like It

To thine own self be true.--Hamlet

Unkindest cut of all.--Julius Caesar

We are such stuff as dreams are made of-- The Tempest

What's past is prologue.-- The Tempest

Woe is me-Hamlet

"Remember first possess his

books; for without them he's but

a so t ... "

Mandel, Susannah. Sparknotes on The Tempest. 19 November 2002.

http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/tempest

Tempest in the Lunchroom, Joseph R. Scotese, Whitney Young Magnet School in Chicago, Illinois

The Folger Shakespeare Library

http://www.folger.edu/education/lesson.dm?lessonid=5

Grode, Eric. "Prospera's Rough Magic." American Theatre Magazine: August, 2003.

Jago, Carol. With Rigor for All. Portsmith, NH: Heinemann, 2000

Scatterbrained Soliloquies, Russ Bartlett, Rutgers Preparatory School in Somerset, New Jersey

The Folger Shakespeare Library

http://www.folger.edu

William Strachey, True Reporty ofthe Wracke as reprinted in the Arden Shakespeare's edition of The

Tempest, ed. Frank Kermode (New York: Routledge, 1994) 135.