Applied Nursing Research 28 (2015) 92–98

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Applied Nursing Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apnr

A retrospective study of nursing diagnoses, outcomes, and

interventions for patients with mental disorders

Paula Escalada-Hernández, PhD, MSc a,⁎, Paula Muñoz-Hermoso, BSc b, Eduardo González–Fraile, Msc, BSc c,

Borja Santos, Msc, BSc d, José Alonso González-Vargas, PMH CNS, BSc e, Isabel Feria-Raposo, PMH CNS, BSc f,

José Luis Girón-García, PMH CNS, BSc g, Manuel García-Manso, BSc h THE CUISAM GROUP 1

a

Public University of Navarre, Pamplona, Spain

Clínica Psiquiátrica Padre Menni, Pamplona, Spain

c

Instituto de Investigaciones Psiquiátricas, Bilbao, Spain

d

Universidad del País Vasco, Bilbao, Spain

e

Complejo Asistencial Hermanas Hospitalarias, Málaga, Spain

f

Benito Menni CASM, Sant Boi, Spain

g

Centro Neuropsiquiátrico Nuestra Sra. Del Carmen, Garrapinillos, Spain

h

Complejo Hospitalario San Luis, Palencia, Spain

b

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 15 August 2013

Revised 24 March 2014

Accepted 28 May 2014

Keywords:

NANDA-I nursing diagnoses

NIC interventions

NOC outcomes

Psychiatric diagnoses

Mental disorders

a b s t r a c t

Aim: The aim of this study is to describe the most frequent NANDA-I nursing diagnoses, NOC outcomes, and

NIC interventions used in nursing care plans in relation to psychiatric diagnosis. Background: Although

numerous studies have described the most prevalent NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels in association with

medical diagnosis in different specialties, only few connect these with psychiatric diagnoses. Methods: This

multicentric cross-sectional study was developed in Spain. Data were collected retrospectively from the

electronic records of 690 psychiatric or psychogeriatric patients in long and medium-term units and,

psychogeriatric day-care centres. Results: The most common nursing diagnoses, interventions and outcomes

were identified for patients with schizophrenia, organic mental disorders, mental retardation, affective

disorders, disorders of adult personality and behavior, mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive

substance use and neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders. Conclusion: Results suggest that

NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels combined with psychiatric diagnosis offer a complete description of the

patients' actual condition.

© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

⁎ Corresponding author at: Health Science Department, Public University of Navarre.,

Avenida de Barañain s/n. 31008, Pamplona, Navarre, Spain. Tel.: +34 948 14 06 11.

E-mail addresses: escalada.paula@gmail.com (P. Escalada-Hernández),

pmunoz@clinicapadremenni.org (P. Muñoz-Hermoso), egonzalezf@aita-menni.org

(E. González–Fraile), bsantos001@hotmail.com (B. Santos),

jagonzalez@hospitalariasmadrid.org (J.A. González-Vargas),

iferia@hospitalbenitomenni.org (I. Feria-Raposo), jlgiron@neuronscarmen.org

(J.L. Girón-García), mgarcia@sanluis.org (M. García-Manso).

1

The researchers who were part of the CUISAM Group were: Uxua Lazkanotegui

Matxiarena, Itxaso Marro Larrañaga, Janire Martínez Berrueta, Miren Arbelóa Álvarez,

Miriam García Sanabria, David Rodríguez Merchán, Cristina Flores Del Redal López and

Marta Alameda Blanco from Clínica Psiquiátrica Padre Menni (Pamplona, Spain);

Mertxe Olondriz Urrutia and Maite Dendarrieta Bardot from Centro Hospitalario Benito

Menni (Elizondo, Spain); Almudena Bueno García, Elena Muñoz Jiménez, Mª Esperanza

Pozo Cambeiro, Inmaculada Romero López, Juan Tomás Jiménez Pereña, Laura Cebreros

Cuberos, Laura Marín Rubio, Marina Rubio Guerrrero, Rocío Jiménez Sánchez, Sergio

Víctor Mata Reyes, Antonia Mª Ariza Nevado and Verónica Aguilar Pérez from Complejo

Asistencial Hermanas Hospitalarias (Málaga, Spain); Mª Carmen Vilchez Estévez,

Mónica Pastor Ramos and Alberto Carnero Treviño from Benito Menni CASM (Sant Boi,

Spain); Nuria García Sola, Natividad Izaguerri Mochales, Elena Martínez Araus, Eva Sanz

Báguena, Silvia Gabasa Galbez from Centro Neuropsiquiátrico Nuestra Sra. Del Carmen

(Zaragoza, Spain); Emilio Negro González from Complejo Hospitalario San Luis

(Palencia, Spain).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2014.05.006

0897-1897/© 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Background

Over the last decades, in the context of mental health care, important

reforms have taken place to promote the deinstitutionalization of

patients in many occidental countries (WHO & Wonca, 2008). In this

line, in Spain numerous changes have been undertaken to adopt a

community-based model of mental health care (Ministry of Health,

Equality Social Services, 2012). The Mental Health Strategy of the

Spanish National Health System 2009–2013 is the current guidance

document that, based on the evaluation of the present situation, outlines

the main lines of strategy and objectives for the improvement of mental

health care (Ministry of Health, Equality Social Services, 2012). This

document acknowledges the relevance of nurses' function and

promotes the incorporation of nurses who are certified as psychiatric–

mental health clinical nurse specialist as part of interdisciplinary teams

among all mental health care services. The mental health care services

include a variety of different types of health care settings for adult

patients: community mental health care centres, day care/psychosocial

rehabilitation centres, community residential/supported living services,

P. Escalada-Hernández et al. / Applied Nursing Research 28 (2015) 92–98

acute psychiatric units, medium and long-term psychiatric units and

psychogeriatric residential units (SIAP, 2009).

The nurses' role within the interdisciplinary teams can be

supported and enhanced with research on nursing care and practice

in the different mental health care services of the Spanish context. The

use of standardized languages to describe the elements of the nursing

process provides a systematic approach toward patient care and

allows describing nursing practice in a precise way (Johnson,

Moorhead, Bulechek, Maas, & Swanson, 2011; Nanda International,

2012; Thoroddsen, Ehnfors, & Ehrenberg, 2010). The nursing

diagnoses classification of the NANDA-International (NANDA-I;

Nanda International, 2012), the Nursing Outcomes Classification

(NOC; Moorhead, Johnson, Maas, & Swanson, 2013) and the Nursing

Interventions Classification (NIC; Bulechek, Butcher, Dochterman, &

Wagner, 2013) are three coded and standardized nomenclatures that

refer to the nursing process elements of diagnoses, interventions, and

outcomes. Each element in NANDA-I, NIC and NOC taxonomies

consists of a label name, a definition and a unique numeric code.

NANDA-I, NIC and NOC terminologies have widely been researched

and applied (Anderson, Keenan, & Jones, 2009; Johnson et al., 2011).

The three classifications together have the potential to represent

the domain of nursing in all settings (Johnson et al., 2011).

Thoroddsen et al. (2010) compared nursing diagnoses and nursing

interventions in four selected nursing specialties, including surgical,

medical, geriatric, and psychiatric areas. They concluded that

NANDA-I and NIC taxonomies illustrated the specific knowledge of

each specialty and were very useful in describing basic human needs

and nursing care in clinical practice. Nonetheless, they argued that

further research should be developed to identify specific nursing

diagnoses, nursing interventions and outcomes in different specialties. Two studies identified nursing phenomena (Frauenfelder,

Müller-Staub, Needham, & Van Achterberg, 2011) and nursing

interventions (Frauenfelder, Müller-Staub, Needham, & Achterberg,

2013) mentioned in journal articles on adult psychiatric inpatient

nursing care and compared them with the NANDA-I and NIC

terminologies respectively. Both studies concluded that these taxonomies described the majority, but not all, of concepts mentioned in the

literature. The authors suggested that additional development of the

taxonomies is needed to include all the relevant phenomena and

interventions for the nursing work in adult inpatient settings (Frauenfelder et al., 2011, 2013).

Numerous studies in different specialties have analyzed NANDA-I,

NIC and NOC elements in association with medical diagnoses or

diagnosis-related groups. It has been demonstrated that their

concurrent application offers complementary information about a

patient's actual condition that can be employed to predict patient

outcomes or use of resources (Güler, Eser, Khorshid, & Yücel, 2012;

van Beek, Goossen, & van der Kloot, 2005; Welton & Halloran, 2005).

In psychiatry and mental health care, only two studies examining the

prevalence of nursing diagnoses according to different psychiatric

diagnoses have been located. Ugalde Apalategui and Lluch Canut

(2011) described the most prevalent NANDA-I labels for nine

diagnosis-related groups and Vílchez Esteve, Atienza Rodríguez,

Delgado Almeda, González Jiménez, and Lorenzo Tojeiro (2007) for

five psychiatric diagnoses. Moreover, two additional papers examined

nursing diagnoses in patients with a specific psychiatric diagnosis,

such as schizophrenia (Chung, Chiang, Chou, Chu, & Chang, 2010;

Lluch Canut et al., 2009).

Beyond prevalence analyses, several research projects have

examined the relationship between the number of nursing diagnoses,

as a measure of nursing complexity, and patient outcomes. For

example, Moon (2011) found that the number of nursing diagnoses

was significantly related to the changes in selected NOC scores in ICU

patients and Sherb et al. (2013) obtained similar results in patients

with pneumonia or heart failure. In acute cardiac care, Meyer, Wang,

Li, Thomson, and O'Brien-Pallas (2009) demonstrated that the

93

number of nursing diagnoses increased the likelihood of suffering

medical consequences (e.g., medical errors with consequences,

urinary tract or wound infections) and reduce the extent to which

physical and mental health improved at discharge (measured by

difference scores between admission and discharge in the SF-12

Health Status Survey). To the author's knowledge, this aspect has not

been explored in psychiatric patients.

Examining nursing practice by analyzing NANDA-I, NIC and NOC

labels mentioned in nursing records in mental health nursing practice

may contribute to develop knowledge within the specialty. The aim of

this study is to describe the most frequent nursing diagnoses,

outcomes, and interventions used in nursing care plans for psychiatric

and psychogeriatric patients in medium and long-term care facilities

in relation to psychiatric diagnosis. The research questions were:

(a) Which nursing diagnoses, outcomes and interventions are used in

nursing care plans according to psychiatric diagnosis? (b) Is there any

relationship between the variables number of nursing diagnoses,

psychiatric diagnosis, age or gender and the degree of severity of

problems associated with mental illness?

2. Research methods

2.1. Data collection procedures and sample

This multicentric cross-sectional study was performed in 5

psychiatric clinics in different regions of Spain. These centres belong

to the Congregation of Sisters Hospitallers of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

The electronic medical record software used in these centres

integrates NANDA-I, NIC and NOC taxonomies and nurses have used

them routinely to develop healthcare plans for some years now.

Data were collected retrospectively from the nursing care plans

included in the electronic patient records. No sampling strategy was

used as the whole study population was included in the study. The

study population consisted of all those records of patients fulfilling the

inclusion/exclusion criteria who were hospitalized between June

2010 and July 2011. Subjects eligible for inclusion were adult (aged

over 18) psychiatric and psychogeriatric patients, who had a nursing

care plan with NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels and stayed at any of the

healthcare facilities under study. These were long-term psychiatric

units, medium-term psychiatric units, long-term psychogeriatric units

and psychogeriatric day-care centres. Long-term units are residential

services and patients may stay there indefinitely. Patients usually stay

in medium-term units between 1 and 6 months. As exclusion criteria,

due to ethical considerations, all patients in a terminal condition were

not considered eligible. Records of patients who were readmitted

after discharge during the data collection period were excluded.

This research project was approved by the Ethical and Scientific

Research Committee of Navarra. To ensure anonymity each electronic

patient record was assigned an ID-number. Access to medical electronic

records was granted by participating centres. In addition, although not

necessary, written informed consent from all participants or their legal

guardians was obtained to add ethical value to the study. In order to

facilitate a systematic data collection, all members of the research team

used a data collection form and received a training session.

2.2. Variables

The content of the data collection form consisted of 4 data sets

relating to socio-demographic details, medical information, NANDA-I,

NIC and NOC codes and the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale

(HoNOS), respectively. The socio-demographic details collected were

age, gender, marital status, socio-economic status, education and

employment situation. The medical information included primary

psychiatric diagnosis according to ICD-10 classification (secondary

diagnoses, if present, were not considered), clinical area (psychiatry

or psychogeriatry) and type of healthcare setting (i.e. day-care centre,

94

P. Escalada-Hernández et al. / Applied Nursing Research 28 (2015) 92–98

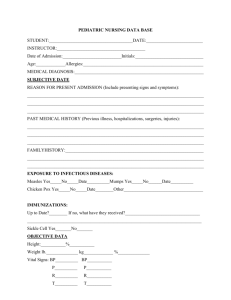

Table 1

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample.

Data

Age groups

19–30 year

31–50 years

51–65 years

66–85 years

≥85 years

Gender

Women

Men

Marital status

Single

Married

Divorced/Separated

Widower

Unkown

Socio-economic status

Low

Low-medium

Medium

High-medium

High

Unkown

Education

Illiterate

Primary school level

Secondary school level

University level

Unknown

Employment situation

Employed

Unemployed

In pension

n

%

15

101

153

326

96

2.17

14.62

22.14

47.18

13.89

432

257

62.70

37.30

381

99

60

130

21

55.14

14.33

8.68

18.81

3.04

179

173

156

63

16

104

25.90

25.04

22.57

9.12

2.32

15.05

74

332

100

51

134

10.71

48.05

14.47

7.38

19.39

6

75

602

0.88

10.98

88.14

medium or long-term unit). In relation to NANDA-I, NIC and NOC

taxonomies, the codes of nursing diagnoses, outcomes and interventions documented in nursing care plans were recorded. In addition,

clinical problems and social functioning of patients were assessed by

HoNOS in its Spanish version (Uriarte et al., 1999). HoNOS is an

instrument with 12 items designed to measure the whole range of

physical, personal and social problems associated with mental illness.

The score in each item ranges from 0 (i.e. without problems) to 4

(serious or very serious problems). Thus, the total HoNOS score may

range from 0 to 48.

This scale has a broad clinical and a social coverage; it is used as a

clinical outcome measure and is suitable for routine application by

nurses (Pirkis et al., 2005; Wing et al., 1998). Different studies of the

psychometric properties of the scale showed an adequate internal

consistence with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.59 to 0.76,

indicating that HoNOS provides a clear overview of severity of

symptoms (Pirkis et al., 2005). Studies that analyzed the test–retest

reliability of the scale have reported fair to moderate scores and those

that examined its inter-rater reliability concluded that overall

agreement between raters was moderate to good for the HoNOS

total score (Pirkis et al., 2005).

2.3. Data analyses

Data were analyzed with MS Excel and STATA V.12.1 software

(StataCorp LP). To determine the most frequent NANDA-I, NIC and

NOC labels in relation to psychiatric diagnosis, the sample was divided

into groups according psychiatric diagnosis categories. Descriptive

analyses were performed using absolute frequency distribution and

percentage. For the second research question, additional statistical

analyses were executed on the data from the total sample. The

Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to explore the relationship between the number of nursing diagnoses and the total score in

HoNOS. A multiple regression model was performed where total

HoNOS score was the independent variable and the dependent

variables were psychiatric diagnosis, number of nursing diagnoses,

age and gender.

3. Results

Socio-demographic information of the study sample is presented

in Table 1. The final sample included the records of 690 patients. From

them, 434 (62.90%) were female and 256 (37.10%) were male. The

average age was 67.9 ± 16.8 years (range 19–101). More than 50% of

subjects were married, around 70% had a socio-economic status

between low and medium, the majority (88%) were in pension and

approximately 50% had primary school level education. The number

of participants admitted in long-term psychiatric units was 219

(31.74%), 54 (7.83%) in medium-term psychiatric units, 351 (50.87%)

in long-term psychogeriatric units and, 66 (9.56%) in psychogeriatric

day-care centres.

Psychiatric diagnoses were classified according to the main

categories of ICD-10, obtaining the following groups: group 1:

schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (n = 362;

52.46%); group 2: organic mental disorders (n = 182; 26.38%);

group 3: mental retardation (n = 37; 5.36%); group 4: bipolar

affective disorders (n = 33; 4.78%); group 5: depressive and other

affective disorders (n = 22; 3.19%); group 6: disorders of adult

personality and behaviour (n = 21; 3.04%); group 7: mental and

behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (n = 17;

2.46%); group 8: neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders

(n = 14; 2.03%); other disorders (n = 2; 0.30%).

Below, the main results will be presented in order of the

research questions.

3.1. (a) Which nursing diagnoses, outcomes and interventions are used

in nursing care plans according to psychiatric diagnosis?

In all, 3681 nursing diagnoses, 4685 nursing outcomes and 13396

nursing interventions were recorded. The average number of nursing

diagnoses per patient was 5.3. Similarly, the average numbers of

nursing outcomes and nursing interventions per patient were 6.8 and

19.4 respectively.

Nursing diagnoses, outcomes and interventions were analyzed

within each psychiatric diagnosis group. The most frequent NANDA-I,

NOC and NIC labels for each group are illustrated in Tables 2A and 2B.

The most prevalent labels are mainly related to psychosocial and

self-care deficit aspects. Certain patterns or profiles were observed

within each psychiatric diagnosis group. In group 1 (schizophrenia,

schizotypal and delusional disorders), NANDA-I, NIC and NOC terms

illustrated the usual needs faced by patients with schizophrenia such

as disturbance of thought processes and social, communication,

anxiety and treatment compliance problems. Nursing diagnoses,

outcomes and interventions in relation to self-care deficit were

more predominant in groups 2 (organic mental disorders) and 3

(mental retardation). Within group 4 (bipolar affective disorders),

NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels are mainly related to self-care deficits

and, symptom and side-effects management (i.e. disturbance of

thought processes and constipation) and treatment compliance.

NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels in groups 5 (depressive and other

affective disorders) and 8 (neurotic, stress-related and somatoform

disorders) showed a special focus on anxiety problems. Groups 6

(disorders of adult personality and behaviour) and 7 (mental and

behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use) had a

majority of nursing diagnoses, outcomes and interventions related to

social interaction and self-care needs. Moreover, some labels in group

7 (mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance

use) referred to side-effects such as constipation.

P. Escalada-Hernández et al. / Applied Nursing Research 28 (2015) 92–98

95

Table 2A

Most frequent NNN labels by psychiatric diagnosis group.

Group 1: schizophrenia, schizotypal

and delusional disorders (n = 362)

Group 2: organic mental

disorders (n = 182)

Group 3: mental

retardation (n = 37)

Group 4: bipolar affective

disorders (n = 33)

NANDA

108 self-care deficit: bathing

130 disturbed thought

processes

52 impaired social interaction

n

%

NANDA

207 57,18 109 self-care deficit: dressing

174 48,07 108 self-care deficit: bathing

n

%

NANDA

122 67,03 108 self-care deficit: bathing

116 63,74 109 self-care deficit: dressing

n

%

NANDA

17 45,95 108 self-care deficit: bathing

15 40,54 11 constipation

n

%

16 48,48

13 39,39

139 38,40 102 self-care deficit: feeding

89

48,90 102 self-care deficit: feeding

8

12 36,36

51 impaired verbal

communication

78 ineffective self health

management

108 29,83 131 impaired memory

71

39,01 11 constipation

7

108 29,83 51 impaired verbal

communication

59

32,42 97 deficient diversional

activity

6

n

%

NOC

168 46,41 300 self-care: activities of daily

living (ADL)

153 42,27 305 self-care: hygiene

n

%

NOC

150 82,42 300 self-care: activities of

daily living (ADL)

105 57,69 305 self-care: hygiene

133 36,74 1101 tissue integrity:

skin and mucous membranes

126 34,81 302 self-care: dressing

80

NOC

305 self-care: hygiene

21,62 130 disturbed thought

processes

18,92 78 ineffective self health

management

16,22 97 deficient diversional

activity

12 36,36

11 33,33

n

%

NOC

19 51,35 1612 weight control

n

9

%

27,27

8

24,24

43,96 302 self-care: dressing

15 40,54 300 self-care: activities of

daily living (ADL)

10 27,03 305 self-care: hygiene

8

24,24

77

42,31 1604 leisure participation

8

8

24,24

1502 social interaction skills 126 34,81 902 cognitive orientation

57

31,32 501 bowel elimination

7

8

24,24

NIC

1801 self-care assistance:

bathing/hygiene

5606 teaching: Individual

n

%

NIC

156 85,71 5606 teaching: individual

n

%

NIC

24 64,86 200 exercise promotion

n

%

23 69,70

137 75,27 1801 self-care assistance:

bathing/hygiene

128 70,33 5820 anxiety reduction

120 65,93 200 exercise promotion

19 51,35 5820 anxiety reduction

20 60,61

5820 anxiety reduction

4820 reality orientation

n

%

NIC

226 62,43 6480 environmental

management

212 58,56 1801 self-care assistance:

bathing/hygiene

194 53,59 5606 teaching: Individual

175 48,34 6490 fall prevention

17 51,52

16 48,48

5100 socialization

enhancement

2380 medication

management

4920 active listening

153 42,27 1802 self-care assistance:

dressing/grooming

152 41,99 6486 environmental

management: safety

147 40,61 1800 self-care assistance

119 65,38 1800 self-care assistance

16 43,24 4820 reality orientation

15 40,54 2300 medication

administration

13 35,14 5606 teaching: individual

12 32,43 1801 self-care assistance:

bathing/hygiene

12 32,43 4920 active listening

14 42,42

4480 self-responsibility

facilitation

5230 coping enhancement

146 40,33 6460 dementia management

115 63,19 6480 environmental

management

107 58,79 1802 self-care assistance:

dressing/grooming

102 56,04 1670 hair care

13 39,39

145 40,06 4820 reality orientation

97

53,30 1680 nail care

92

50,55 1660 foot care

12 32,43 2380 medication

management

11 29,73 4480 self-responsibility

facilitation

11 29,73 5100 socialization

enhancement

1403 distorted thought

self-control

300 self-care: activities of

daily living (ADL)

901 cognitive orientation

4362 behavior modification: 133 36,74 1803 self-care assistance:

social skills

feeding

3.2. (b) Is there any relationship between the variables number of

nursing diagnoses, psychiatric diagnosis, age or gender and the degree of

severity of problems associated with mental illness?

Data from the total sample were used to examine potential

relationships between number of nursing diagnoses, psychiatric

diagnosis, age or gender and the degree of severity of problems

associated with mental illness (as reflected by HoNOS total score). The

mean of the HoNOS score in the total sample was 13.24 ± 5.97. The

result of the Pearson correlation test (r = 0.22) was statistically

significant (p b 0.05) and indicated a moderate positive linear

relationship between HoNOS total score and the number of nursing

diagnoses. Several stepwise regression models were devised to

determine the explanatory factors for the HoNOS total score. Initially,

number of nursing diagnoses, psychiatric diagnoses, age and gender

were included as independent variables the HoNOS total score as

dependent variable. The final multiple regression model (Table 3)

revealed that only gender and number of nursing diagnoses had a

significant influence on the HoNOS total score. The gender coefficient

(− 1.35 ± 0.45) represents that adjusting for the nursing diagnoses,

women would have had a HoNOS total score one point less than men.

According to the coefficient of the number of nursing diagnoses

(0.44 ± 0.07), an increment of five diagnoses adjusting for gender

represents a 2-point increment in the HoNOS total score.

21,62 1403 distorted thought

self-control

18,92 1608 symptom control

15 45,45

14 42,42

13 39,39

13 39,39

4. Discussion

The findings of this study describe the most frequent NANDA-I, NIC

and NOC labels for groups of patients with different psychiatric

diagnoses in medium and long-term units. Overall, some common

aspects among all groups were found. NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels in

all groups reflected nursing care related to patients' psychosocial

needs, self-care deficits and management of the therapeutic regimen.

The domain of psychiatric nursing specialty, although not exclusively,

focuses on these aspects (Frauenfelder et al., 2011; Sales Orts, 2005;

Ugalde Apalategui & Lluch Canut, 2011). Nursing care related to

patients' psychosocial needs were described by nursing diagnoses

such as disturbed thought processes, impaired social interaction,

impaired verbal communication, deficient diversional activity or anxiety;

outcomes such as distorted thought self-control, social interaction skills,

cognitive orientation, leisure participation or anxiety self-control; and

interventions such as active listening, anxiety reduction, socialization

enhancement, reality orientation, exercise promotion or coping enhancement. In relation to self-care needs, for instance, several nursing

diagnoses of self-care deficit (i.e. bathing, dressing, and feeding) and its

related outcomes and interventions can be observed. Furthermore,

NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels such as ineffective self health

management, medication management or medication administration

illustrated how attention to the management of the therapeutic

96

P. Escalada-Hernández et al. / Applied Nursing Research 28 (2015) 92–98

Table 2B

Most frequent NNN labels by psychiatric diagnosis group.

Group 5: depressive and other

affective disorders (n = 22)

NANDA

108 self-care deficit:

bathing

130 disturbed thought

processes

146 anxiety

109 self-care deficit:

dressing

16 impaired urinary

elimination

NOC

305 self-care: hygiene

Group 6: disorders of adult

personality and behavior (n = 21)

Group 7: mental and behavioural

disorders due to psychoactive

substance use (n = 17)

n

%

NANDA

12 54,55 108 self-care deficit: bathing

n

%

NANDA

11 52,38 108 self-care deficit: bathing

9

40,91 97 deficient diversional activity

7

8

7

36,36 52 impaired social interaction

31,82 109 self-care deficit: dressing

6

6

33,33 51 impaired verbal

communication

28,57 52 impaired social interaction 7

28,57 11 constipation

5

7

31,82 78 ineffective self health

management

5

23,81 109 self-care deficit: dressing

4

n

8

n

%

NOC

12 54,55 1604 leisure participation

300 self-care: activities of 8

daily living (ADL)

1403 distorted thought

8

self-control

1502 social interaction skills 7

41,18 146 anxiety

29,41 109 self-care deficit:

dressing

23,53 130 disturbed thought

processes

4

28,57

n

%

NOC

11 64,71 1502 social interaction skills

n

9

%

64,29

10 58,82 305 self-care: hygiene

5

35,71

5

35,71

5

35,71

5

35,71

36,36 305 self-care: hygiene

5

23,81 1604 leisure participation

6

31,82 1101 tissue integrity: skin and

mucous membranes

31,82 300 self-care: activities of daily

living (ADL)

5

23,81 501 bowel elimination

5

35,29 1403 distorted thought

self-control

29,41 1503 social involvement

4

19,05 901 cognitive orientation

5

29,41 1402 anxiety self-control

n

%

NIC

20 90,91 200 exercise promotion

1801 self-care assistance:

bathing/hygiene

5606 teaching: individual

16 72,73 5230 coping enhancement

n

%

NIC

15 71,43 1801 self-care assistance:

bathing/hygiene

12 57,14 200 exercise promotion

12 54,55 4310 activity therapy

11 52,38 5820 anxiety reduction

5230 coping

enhancement

4820 reality orientation

12 54,55 5100 socialization enhancement

2300 medication

administration

4920 active listening

11 50,00 6490 fall prevention

11 52,38 6486 environmental

management: safety

11 52,38 5100 socialization

enhancement

11 52,38 4820 reality orientation

11 50,00 5820 anxiety reduction

n

%

NIC

15 88,24 5820 anxiety reduction

n

%

12 85,71

15 88,24 4362 behavior modification:

social skills

10 58,82 5100 socialization

enhancement

9

52,94 5230 coping enhancement

12 85,71

9

52,94 200 exercise promotion

9

64,29

9

52,94 1801 self-care assistance:

bathing/hygiene

47,06 4310 activity therapy

7

50,00

6

42,86

6

42,86

6

42,86

6

42,86

10 45,45 6486 environmental management: 10 47,62 6490 fall prevention

safety

10 45,45 4920 active listening

10 47,62 5606 teaching: Individual

8

10 45,45 2380 medication management

9

7

41,18 4640 anger control

assistance

41,18 4920 active listening

9

8

6

35,29 4820 reality orientation

40,91 4420 patient contracting

42,86 2300 medication

administration

38,10 1800 self-care assistance

regimen also appeared in the nursing care plans. This supports the

conclusions of Thoroddsen et al. (2010), who demonstrated that

standardized nursing languages have the potential of representing

specific knowledge within nursing specialties, including mental

health nursing.

Within each psychiatric diagnosis group specific patterns and

features can be observed, demonstrating that psychiatric diagnosis

and NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels were related. Findings in group 1

(i.e. patients with schizophrenia) are consistent with the literature.

Three of the most prevalent nursing diagnoses in this group: disturbed

thought processes, ineffective self health management and self-care

deficit: bathing were also found very frequent in other studies on

Table 3

Final multiple regression model.

Dependent variable: HoNOS score

Significance

2

R = 0.566

0.000

Model

Stand coefficient Significance CI 95%

(independent variables) (beta)

Low

−1.353

0.439

0.003

0.000

High

−2.247 −0.459

0.292

0.586

35,71

35,71

28,57

6

NIC

5820 anxiety reduction

%

50,00

5

4

36,36 1209 motivation

7

Gender

Number of diagnoses

n

%

NANDA

n

13 76,47 52 impaired social

7

interaction

8

47,06 108 self-care deficit: bathing 5

%

NOC

38,10 300 self-care: activities of

daily living (ADL)

28,57 305 self-care: hygiene

4 sleep

2380 medication

management

6486 environmental

management: Safety

1850 sleep enhancement

Group 8: neurotic, stress-related and

somatoform disorders (n = 14)

7

10 71,43

10 71,43

patients with schizophrenia and schizotypal and delusional disorders

(Chung et al., 2010; Lluch Canut et al., 2009; Ugalde Apalategui &

Lluch Canut, 2011; Vílchez Esteve et al., 2007) For the rest of the

psychiatric diagnosis groups, comparisons between this study and the

other two existing studies are difficult as they classified psychiatric

diagnoses in a different way, using diagnosis-related groups (Ugalde

Apalategui & Lluch Canut, 2011) or other diagnostic categories such as

mania, depression, dual disorders or adaptative disorders (Vílchez

Esteve et al., 2007). Clinical manifestations and diagnostic criteria

differ among classifications, and therefore, patients' characteristics

and needs in each group will be different in some degree.

The statistical analyses performed showed that HoNOS total score

was related with the variable number of nursing diagnoses and not

with the variable psychiatric diagnosis. Based on these results, it could

be argued that the degree of severity of patients' problems has an

impact on nursing care requirements. This relationship between

patients' level of physical and mental health and number of nursing

diagnoses has been demonstrated in previous research (Meyer et al.,

2009). This result supports the use of number of nursing diagnoses as

a measure of nursing complexity that could be used as predictors of

patient outcomes (Meyer et al., 2009; Moon, 2011; Sherb et al., 2013).

Nursing diagnoses may provide relevant data that could be applied to

inform predictions or management decisions about nurse staffing or

P. Escalada-Hernández et al. / Applied Nursing Research 28 (2015) 92–98

resource utilisation (Hoi, Ismail, Ong, & Kang, 2010; Meyer et al.,

2009; Morales-Asencio et al., 2009).

The results of this study offer a broad picture of the nursing care to

psychiatric and psychogeriatric patients in medium and long-term

care settings, as they included the three main aspects of the nursing

process (i.e. nursing diagnoses, interventions and outcomes). In

addition, information about the specific nursing care needs in relation

to a determined psychiatric diagnosis has been obtained. Thus, the

present study contributes, to some extent, to complete the existing

evidence. As explained above, only a small number of studies

examining nursing diagnoses in association to specific psychiatric

diagnoses were located and research on NANDA-I, NIC or NOC

taxonomies in psychiatry and mental health has been mainly

developed in acute care or community settings and only included

either nursing diagnoses or nursing interventions (Escalada Hernández,

Muñoz Hermoso, & Marro Larrañaga, 2013). Additional research is

needed to complete and validate the findings of this study. The

evidence obtained from this kind of studies will contribute to

reinforce the mental health nurses' role within multidisciplinary

teams as can be applied for evidence-based practice, planning

continuing education programs, the improvement of the quality

of care, the development of standardized care plans and to

provide evidence of the value of mental health nurses' work to

stakeholders (Jones, Lunney, Keenan, & Moorhead, 2010; Nanda

International, 2012).

The present study has some potential limitations. Data were

obtained retrospectively from electronic patient records and not from

direct observation of nurses' work. Therefore, the study results

illustrate documented care and not delivered care. The use of

standardized language has been shown to improve the amount and

quality of data documented (Saranto et al., 2013). However, other

studies have found that nurses tend to communicate and register less

activities than those they actually perform (De Marinis et al., 2010;

Jefferies, Johnson, & Griffiths, 2010). On the other hand, as the sample

was divided into groups according to psychiatric diagnosis, the total

number of patients in the groups related to less prevalent pathologies

is very low. Therefore, findings from these groups should be examined

with caution and future studies focusing on those psychiatric

disorders are needed to complete these results.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that the most common nursing

diagnoses, interventions and outcomes documented in nursing care

plans for psychiatric and psychogeriatric patients admitted in

medium and long-term care units and psychogeriatric day-care

centres are mainly related to psychosocial, self-care deficits and

management of the therapeutic regiment. The most frequent

NANDA-I, NIC and NOC labels for each psychiatric diagnosis have

been identified and specific patterns and differences between groups

can be observed. Furthermore, the degree of severity of problems

associated with mental illness, measured by HoNOS, has been shown

to be related to the number of nursing diagnoses recorded in the care

plan and not to the patient's psychiatric diagnosis. From the findings

presented here, it could be concluded that NANDA-I, NIC and NOC

labels combined with psychiatric diagnoses offer a comprehensive

description of psychiatric and psychogeriatric patients' actual condition, their problems and needs.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Fundación Mª Josefa Recio and the Clínica

Psiquiátrica Padre Menni who funded this project and supported

its development.

Borja Santos was supported by the Department of Education,

Universities and Research of the Government of the Basque Country

97

(DEUI) through the Training and Development Programs for Research

Staff (BFI-2011-212).

The authors would like to thank Sr Patricia Grady ODN for the

valuable review of the manuscript for English usage.

References

Anderson, C. A., Keenan, G., & Jones, J. (2009). Using bibliometrics to support your selection

of a nursing terminology set. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 27(2), 82–90, http://dx.

doi.org/10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181972a24, (http://journals.lww.com/cinjournal/

Fulltext/2009/03000/Using_Bibliometrics_to_Support_Your_Selection_of_a.5.aspx).

Bulechek, G. M., Butcher, H. K., Dochterman, J. M., & Wagner, C. (2013). Nursing

Interventions Classification (NIC) (6th ed.). St Louis: Elsevier/Mosby.

Chung, M. -H., Chiang, I. J., Chou, K. -R., Chu, H., & Chang, H. -J. (2010). Inter-rater and

intra-rater reliability of nursing process records for patients with schizophrenia.

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(21–22), 3023–3030, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.

1365-2702.2010.03301.x.

De Marinis, M. G., Piredda, M., Pascarella, M. C., Vincenzi, B., Spiga, F., & Tartaglini, D.

(2010). ‘If it is not recorded, it has not been done!’? Consistency between nursing

records and observed nursing care in an Italian hospital. Journal of Clinical Nursing,

19(11–12), 1544–1552, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03012.x.

Escalada Hernández, P., Muñoz Hermoso, P., & Marro Larrañaga, I. (2013). La atención

de enfermería a pacientes psiquiátricos definida por la taxonomía NANDA-NICNOC: Una revisión de la literatura. [Nursing care for psychiatric patients defined by

NANDA-NIC-NOC Terminology: A literature review]. Revista ROL de enfermería,

36(3), 166–177.

Frauenfelder, F., Müller-Staub, M., Needham, I., & Achterberg, T. (2013). Nursing

interventions in inpatient psychiatry. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health

Nursing, 20(10), 921–931, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12040.

Frauenfelder, F., Müller-Staub, M., Needham, I., & Van Achterberg, T. (2011). Nursing

phenomena in inpatient psychiatry. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health

Nursing, 18(3), 221–235.

Güler, E. K., Eser, Ï., Khorshid, L., & Yücel, S.Ç. (2012). Nursing diagnoses in elderly

residents of a nursing home: A case in Turkey. Nursing Outlook, 60(1), 21–28, http://

dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2011.03.007.

Hoi, S. Y., Ismail, N., Ong, L. C., & Kang, J. (2010). Determining nurse staffing needs: The

workload intensity measurement system. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(1),

44–53, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01045.

Jefferies, D., Johnson, M., & Griffiths, R. (2010). A meta-study of the essentials of quality

nursing documentation. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(2), 112–124,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01815.x.

Johnson, M., Moorhead, S., Bulechek, G. M., Maas, M. L., & Swanson, E. A. (2011). NOC

and NIC linkages to NANDA-I and clinical conditions: Supporting critical reasoning and

quality care (3rd ed.). Maryland Heights: Elsevier/Mosby.

Jones, D., Lunney, M., Keenan, G., & Moorhead, S. (2010). Standardized nursing

languages: Essential for the nursing workforce. Annual Review of Nursing Research,

28(1), 253–294, http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/0739-6686.28.253.

Lluch Canut, M. T., Sabadell Gimeno, M., Puig Llobet, M., Cencerrado Muñoz, M. A., Navas

Alcal, D., & Ferret Canale, M. (2009). Diagnósticos enfermeros en pacientes con

trastorno mental severo con seguimiento de enfermería en centros de salud mental.

Revista Presencia, 5(10), (http://www.index-f.com/presencia/n10/p7151.php).

Meyer, R. M., Wang, S., Li, X., Thomson, D., & O'Brien-Pallas, L. (2009). Evaluation of a

patient care delivery model: Patient outcomes in acute cardiac care. Journal of Nursing

Scholarship, 41(4), 399–410, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01308.x.

Ministry of Health, Equality Social Services (2012). Mental health strategy of the

Spanish National Health System 2009–2013, Retrieved from. http://www.msssi.

gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/docs/saludmental/MentalHealth

StrategySpanishNationalHS.pdf.

Moon, M. (2011). Relationship of nursing diagnoses, nursing outcomes, and nursing

interventions for patient care in intensive care units. (Doctoral dissertation). Iowa:

University of Iowa (Retrieved from http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/3356).

Moorhead, S., Johnson, M., Maas, M. L., & Swanson, E. (2013). Nursing Outcomes Classification

(NOC), measurement of health outcomes (5th ed.). St Louis: Elsevier Mosby.

Morales-Asencio, J. M., Morilla-Herrera, J. C., Martín-Santos, F. J., GonzaloJiménez, E., Cuevas-Fernández-Gallego, M., & Bonill de las Nieves, C.

(2009). The association between nursing diagnoses, resource utilisation

and patient and caregiver outcomes in a nurse-led home care service:

Longitudinal study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(2), 189–196,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.09.011.

Nanda International (2012). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2012–14.

Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Pirkis, J. E., Burgess, P. M., kirk, P. K., Dodson, S., Coombs, T. J., & Williamson, K.

(2005). A review of the psychometric properties of the Health of the Nation

Outcome Scales (HoNOS) family of measures. Health and Quality of Life

Outcomes, 3(76), http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-3-76, (Retrived from

http://www.hqlo.com/content/3/1/76).

Sales Orts, R. (2005). Análisis del proceso de cuidados de enfermería en una sala de psiquiatría.

(Doctoral dissertation). Sevilla (Spain): Universidad de Sevilla, (Retrieved from http://

ns5.argo.es/cas/prof/enfermeria/observatorio/tesistotal.pdf).

Saranto, K., Kinnunen, U. -M., Kivekäs, E., Lappalainen, A. -M., Liljamo, P., &

Rajalahti, E. (2013). Impacts of structuring nursing records: a systematic

review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, Advance online publication,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/scs.12094.

98

P. Escalada-Hernández et al. / Applied Nursing Research 28 (2015) 92–98

Sherb, C. A., Head, B. J., Hertzog, M., Swanson, E., Reed, D., & Maas, M.

(2013). Evaluation of outcome change scores for patients with pneumonia or heart failure. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 35(1), 117–140,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0193945911401429.

SIAP (Sistema de Información de Atención Primaria del SNS) (2009). Atención a la salud

mental. Retrieved from, http://www.msssi.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidad

SNS/pdf/excelencia/salud_mental/Salud_Mental_2009.pdf

Thoroddsen, A., Ehnfors, M., & Ehrenberg, A. (2010). Nursing specialty knowledge as

expressed by standardized nursing languages. International Journal of Nursing

Terminologies and Classifications, 21(2), 69–79, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744618X.2010.01148.x.

Ugalde Apalategui, M., & Lluch Canut, M. T. (2011). Estudio multicéntrico del uso y utilidad

de las Taxonomías Enfermeras en Unidades de Hospitalización Psiquiátrica. [Informe

de trabajo publicado bajo licencia Creative Commons. Diposit Digital de la Universitat

de Barcelona, apartat Recerca.]. Retrieved from. http://hdl.handle.net/2445/19207.

Uriarte, J. J., Beramendi, V., Medrano, J., Wing, J. K., Beevor, A. S., & Curtis, R. (1999).

Presentación de la traducción al castellano de la Escala HoNOS (Health of the Nation

Outcome Scales). [Presentation of the HoNOS Spanish translation (Health of the

Nation Outcome Scales]. Psiquiatría Pública, 11(4), 37–45.

van Beek, L., Goossen, W. T. F., & van der Kloot, W. A. (2005). Linking nursing care to

medical diagnoses: Heterogeneity of patient groups. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 74, 926–936, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.07.006.

Vílchez Esteve, M. C., Atienza Rodríguez, E., Delgado Almeda, M., González Jiménez, J., &

Lorenzo Tojeiro, M. (2007). Estandarización de los cuidados de enfermería en la

esquizofrenia según el modelo conceptual de Nancy Roper. Revista presencia, 3(5),

(http://www.index-f.com/presencia/n5/62articulo.php).

Welton, J. M., & Halloran, E. J. (2005). Nursing diagnoses, diagnosis-related group, and

hospital outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 35(12), 541–549.

WHO, W. H. O., & Wonca, W. O. o. F. D. (2008). Integrating mental health into primary

care: A global perspective. Retrieved from. http://www.who.int/mental_health/

policy/Integratingmhintoprimarycare2008_lastversion.pdf?ua=1.

Wing, J. K., Beevor, A. S., Curtis, R. H., Park, S. B., Hadden, S., & Burns, A. (1998). Health of

the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS). Research and development. British Journal of

Psychiatry, 172, 11–18, http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.172.1.11.