From Parmigianino to Andy Warhol or Conceptions of Mannerism in

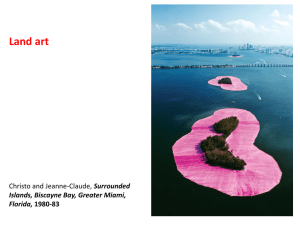

advertisement