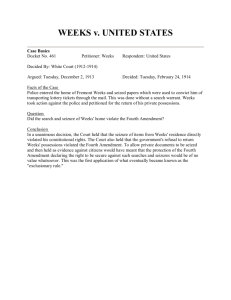

the rise and fall of the exclusionary rule

advertisement