The Economic and Social Consequences of Liquor Privatization in

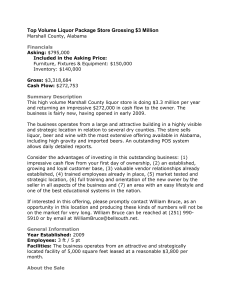

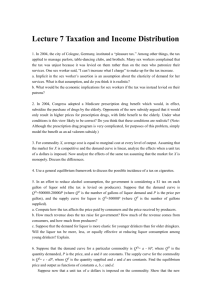

advertisement