Western_Frontier_files/Cultures Clash

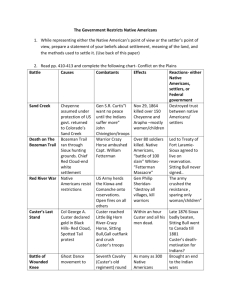

THE MASSACRE AT SAND CREEK

The struggle would be violent. Despite numerous treaties, the demand for native lands simply grew and grew to the point at which rational compromise collapsed. Local volunteer militias formed in the West to ensure its safe settlement and development. The Native Americans were growing increasingly intolerant of being pushed on to less desirable territory.

The brutality that followed was as gruesome as any conflict in United States history. Accelerated by the Sand

Creek Massacre, the two sides slipped down a downward spiral of vicious battle from the end of the Civil War until the 1890s.

Massacre

Sand Creek was a village of approximately 800

Library of Congress

Colonel John M.

Chivington attacked an unsuspecting village of Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indians camped on Sand

Creek.

Cheyenne Indians in southeast Colorado. Black Kettle, the local chief, had approached a United States Army fort seeking protection for his people. On November 28, 1864, he was assured that his people would not be disturbed at Sand Creek, for the territory had been promised to the Cheyennes by an 1851 treaty. The next day would reveal that promise as a baldfaced lie.

On the morning of November 29, a group called the Colorado Volunteers surrounded Sand Creek. In hope of defusing the situation, Black Kettle raised an American flag as a sign of friendship. The Volunteers' commander,

Colonel John Chivington, ignored the gesture. "Kill and scalp all, big and little," he told his troops. With that, the regiment descended upon the village, killing about 400 people, most of whom were women and children.

The brutality was extreme. Chivington's troops committed mass scalpings and disembowelments.

Chief Black Kettle

Some Cheyennes were shot while trying to escape, while others were shot pleading for mercy. Reports indicated that the troops even emptied their rifles on distant infants for sport. Later, Chivington displayed his scalp collection to the public as a badge of pride.

Retaliation

When word spread to other Indian communities, it was agreed that the whites must be met by force. Most instrumental in the retaliation were Sioux troops under the leadership of Red Cloud. In 1866, Sioux warriors ambushed the command of William J. Fetterman, whose troops were trying to complete the construction of the Bozeman Trail in Montana. Of Fetterman's 81 soldiers and settlers, there was not a single survivor. The bodies were grotesquely mutilated.

Faced with a stalemate, Red Cloud and the United States agreed to the 1868

Treaty of Fort Laramie, which brought a temporary end to the hostilities. Large tracts of land were reaffirmed as Sioux and Cheyenne Territory by the United

States Government. Unfortunately, the peace was short-lived.

CUSTER’S LAST STAND

Another Broken Treaty

Gold broke the delicate peace with the Sioux. In 1874, a scientific exploration group led by General George Armstrong Custer discovered the precious metal in the heart of the Black Hills of South Dakota.

When word of the discovery leaked, nothing could stop the masses of prospectors looking to get rich quick, despite the treaty protections that awarded that land to the Sioux. Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, the local Indian leaders, decided to take up arms to defend their dwindling land supply.

Little Big Horn

Custer was perhaps the most flamboyant and brash officer in the United States

Army. He was confident that his technologically superior troops could contain the

Native American fighters. Armed with new weapons of destruction such as the rapid-firing Gatling gun, Custer and his soldiers felt that it was only a matter of time before the Indians would surrender and submit to life on a smaller reservation. Custer hoped to make that happen sooner rather than later.

His orders were to locate the Sioux encampment in the Big Horn Mountains of

Montana and trap them until reinforcements arrived. But the prideful Custer sought to engage the Sioux on his own.

An artist's interpretation of the Battle of Little Big Horn

On June 25, 1876, he discovered a small Indian village on the banks of the Little

Big Horn River. Custer confidently ordered his troops to attack, not realizing that he was confronting the main Sioux and Cheyenne encampment. About three thousand Sioux warriors led by Crazy Horse descended upon Custer's regiment, and within hours the entire Seventh Cavalry and General Custer were massacred.

The victory was brief for the warring Sioux. The rest of the United States regulars arrived and chased the Sioux for the next several months. By October, much of the resistance had ended. Crazy Horse had surrendered, but Sitting Bull and a small band of warriors escaped to Canada.

Eventually they returned to the United States and surrendered because of hunger.

Reactions Back East

Custer's Last Stand caused massive debate in the East. War hawks demanded an immediate increase in federal military spending and swift judgment for the noncompliant Sioux.

Critics of United States policy also made their opinions known. The most vocal detractor,

Helen Hunt Jackson, published A Century of

Dishonor in 1881. This blistering assault on

United States Indian policy chronicled injustices toward Native Americans over the past hundred years.

Crazy Horse

The American masses, however, were unsympathetic or indifferent. A systematic plan to end all native resistance was approved, and the Indians of the West would not see another victory like the Little Big Horn.

THE END OF RESISTANCE

The crackdown on Native Americans did not end with the pursuance of Custer's attackers. Any tribes resisting American advancement were relentlessly hunted by settlers and federal troops. The Lakota Sioux that fought for their lands were decimated by yet another American tactic.

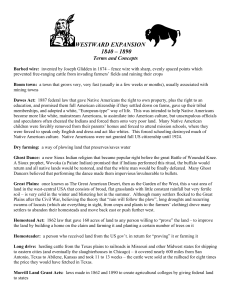

Decimation of the Buffalo

Travelers west were encouraged to kill any buffalo they encountered. Buffalo robes became fashionable in the East, so profit-seekers slaughtered thousands of bison simply for their hides. Others shot them for sport, leaving their remains for the local vultures.

The army was even known to use Gatling guns on the herds to reduce their numbers. The plan was effective. At the end of the Civil War, an estimated 15 million buffalo roamed the Great Plains. By 1900, there were only several hundred, as the species was nearly extinct. The Sioux lost their chief means of subsistence and mourned the loss of the animal, which was revered as sacred according to tribal religion.

Chief Joseph and the Nez Percé

The year after Custer's infamous defeat, the Nez Percé Indians of Idaho fell

"I have heard talk and talk, but nothing is done.

Good words do not last long unless they amount to something. Words do not pay for my dead people. They do not pay for my country, now overrun by white men. Good words will not give my people good health and stop them from dying. Good words will not get my people a home where they can live in peace and take care of themselves. I am TIRED of talk that comes to nothing."

-Chief Joseph

victim to western expansion. When gold was discovered on their lands in 1877, demands were made for over 90 percent of their land. After a stand-off between tribal warriors and the United States Army, their leader Chief Joseph directed his followers toward Canada to avoid capture. He hoped to join forces with Sitting

Bull and plan the next move from there.

Army officials chased the Nez Percé 1700 miles across Idaho and Western

Montana. As they neared the border, the army closed in and Chief Joseph was forced to surrender. The entire tribe was relocated to Oklahoma where nearly half of them perished from disease and despair.

Geronimo and the Apache Struggle

Warfare also raged across the American Southwest. The Apache tribe led one of the longest and fiercest campaigns of all. Under the leadership of Geronimo,

Apache attackers assaulted settlers in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. The army responded slowly but surely. Geronimo was relentlessly hunted, even across the Mexican border.

Finally, after the army seized female Apaches and deported them to Florida and deprived the warring tribesmen of a food supply, Geronimo was captured. His

1886 defeat marked the end of open resistance by Native Americans in the West.

Sooners Grab Oklahoma

The last land to be claimed by homesteaders was in Oklahoma. Previously dubbed "Indian Territory" by the federal government, Oklahoma had been used as a state-sized reservation of many tribes ranging from the Nez Percé in

Idaho to the Cherokee of Georgia.

In 1889, the United States Government decided to open two million acres of land unassigned to any particular tribe for homesteaders. At noon on April 22,

1889, the land was legally opened to claim under the provisions of the

Homestead Act. Thousands rushed across Oklahoma to grab a piece.

Highlighted by a few gunshots, former

This 1895 map shows many of the Native

American tribes which suffered forced relocation to Oklahoma Territory.

Indian land was gobbled up in a matter of hours.

By nightfall, Oklahoma City qualified as a city of 10,000 tent inhabitants. Those who dared to stake a claim before it was legal were called Sooners, and the state acquired its future nickname. Successful homesteaders rested that night in triumph, leaving the Indians of the area to despair over yet another grand theft.

LIFE ON THE RESERVATIONS

After being forced off their native lands, many American Indians found life to be most difficult. Beginning in the first half of the 19th century, federal policy dictated that certain tribes be confined to fixed land plots to continue their traditional ways of life.

The problems with this approach were manifold. Besides the moral issue of depriving a people of life on their historic land, many economic issues plagued the reservation. Nomadic tribes lost their entire means of subsistence by being constricted to a defined area. Farmers found themselves with land unsuitable for agriculture. Many lacked the know-how to implement complex irrigation systems. Hostile tribes were often forced into the same proximity. The results were disastrous.

National Archives

Geronimo (on the right) and his son waiting for a train that transported them and other Apache prisoners to

Florida, in 1886.

The Dawes Act

Faced with disease, alcoholism, and despair on the reservations, federal officials changed directions with the Dawes Severalty Act of

1887. Each Native American family was offered 160 acres of tribal land to own outright. Although the land could not be sold for 25 years, these new land owners could farm it for profit like other farmers in the West.

Congress hoped that this system would end the dependency of the tribes on the federal government, enable Indians to become individually prosperous, and assimilate the Indians into mainstream American life. After 25 years, participants would become American citizens.

The Dawes Act was widely resisted. Tribal leaders foretold the end of their ancient folkways and a further loss of communal land. When individuals did attempt this new way of life, they were often unsuccessful. Farming the West takes considerable expertise. Lacking this knowledge, many were still dependent upon the government for assistance.

Many 19th century Americans saw the Dawes Act as a way to "civilize" the

Native Americans. Visiting missionaries attempted to convert the Indians to

Christianity, although they found few new believers.

"Americanizing" the Indians

Land not allotted to individual landholders was sold to railroad companies and settlers from the East. The proceeds were used to set up schools to teach the reading and writing of English. Native American children were required to attend the established reservation school. Failure to attend would result in a visit by a truant officer who could enter the home accompanied by police to search for the absent student. Some parents felt resistance to "white man education" was a matter of honor.

In addition to disregarding tribal languages and religions, schools often forced the pupils to dress like eastern Americans. They were given shorter haircuts. Even the core of individual identity — one's name — was changed to "Americanize" the children. These practices often led to further tribal divisions. Each tribe had those who were friendly to American "assistance" and those who were hostile.

Friends were turned into enemies.

The Dawes Act was an unmitigated disaster for tribal units. In 1900, land held by

Native American tribes was half that of 1880. Land holdings continued to dwindle in the early 20th century. When the Dawes Act was repealed in 1934, alcoholism, poverty, illiteracy, and suicide rates were higher for Native Americans than any other ethnic group in the United States. As America grew to the status of a world power, the first Americans were reduced to hopelessness.

THE WOUNDED KNEE MASSACRE

The armed resistance was over. The remaining Sioux were forced into reservation life at gunpoint. Many Sioux sought spiritual guidance. Thus began a religious awakening among the tribes of North America.

Arrival of the "Ghost Dance"

Called the "Ghost Dance" by the white soldiers who observed the new practice, it spread rapidly across the continent. Instead of bringing the answer to their prayers, however, the "Ghost Dance" movement resulted in yet another human travesty.

It all began in 1888 with a Paiute holy man called Wovoka. During a total eclipse of the sun, Wovoka received a message from the Creator. Soon an Indian messiah would come and the world would be free of the white man. The Indians could return to their lands and the buffalo would once again roam the Great

Plains.

Wovoka even knew that all this would happen in the spring of 1891. He and his followers meditated, had visions, chanted, and performed what became known as the Ghost Dance. Soon the movement began to spread. Before long, the

Ghost Dance had adherents in tribes throughout the South and West.

Although Wovoka preached nonviolence, whites feared that the movement would spark a great Indian rebellion. Ghost Dance followers seemed more defiant than other Native Americans, and the rituals seemed to work its participants into a frenzy. All this was disconcerting to the soldiers and settlers throughout the

South and West. Tragedy struck when the Ghost Dance movement reached the

Lakota Sioux.

Local residents of South Dakota demanded that the Sioux end the ritual of the

Ghost Dance. When they were ignored, the United States Army was called for assistance. Fearing aggression, a group of 300 Sioux did leave the reservation.

Army regulars believed them to be a hostile force preparing for attack. When the two sides came into contact, the Sioux reluctantly agreed to be tranported to

Wounded Knee Creek on Pine Ridge

Reservation.

A Final Tragedy

On the morning of December 29, 1890, the army demanded the surrender of all

Sioux weapons. Amid the tension, a shot rang out, possibly from a deaf brave who misunderstood his chief's orders to surrender.

The Seventh Cavalry — the reconstructed regiment lost by George

Armstrong Custer — opened fire on the

Sioux. The local chief, Big Foot, was shot in cold blood as he recuperated from pneumonia in his tent. Others were cut down as they tried to run away.

When the smoke cleared almost all of the 300 men, women, and children were dead. Some died instantly, others froze to death in the snow.

This massacre marked the last showdown between Native Americans and the United States Army. It was nearly 400 years after Christopher

Columbus first contacted the first

Americans. The 1890 United States census declared the frontier officially closed.

from USHistory.org

Congressional Medals of Honor were awarded to many of the cavalrymen who fought at Wounded Knee. Despite the current view that the battle was a massacre of innocents, the Medals still stand. Some native American and other groups and individuals continue to lobby

Congress to rescind these "Medals of dis-

Honor."