Death Be Not Proud: Poem, Summary & Analysis

advertisement

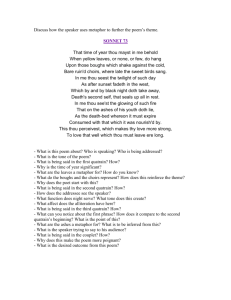

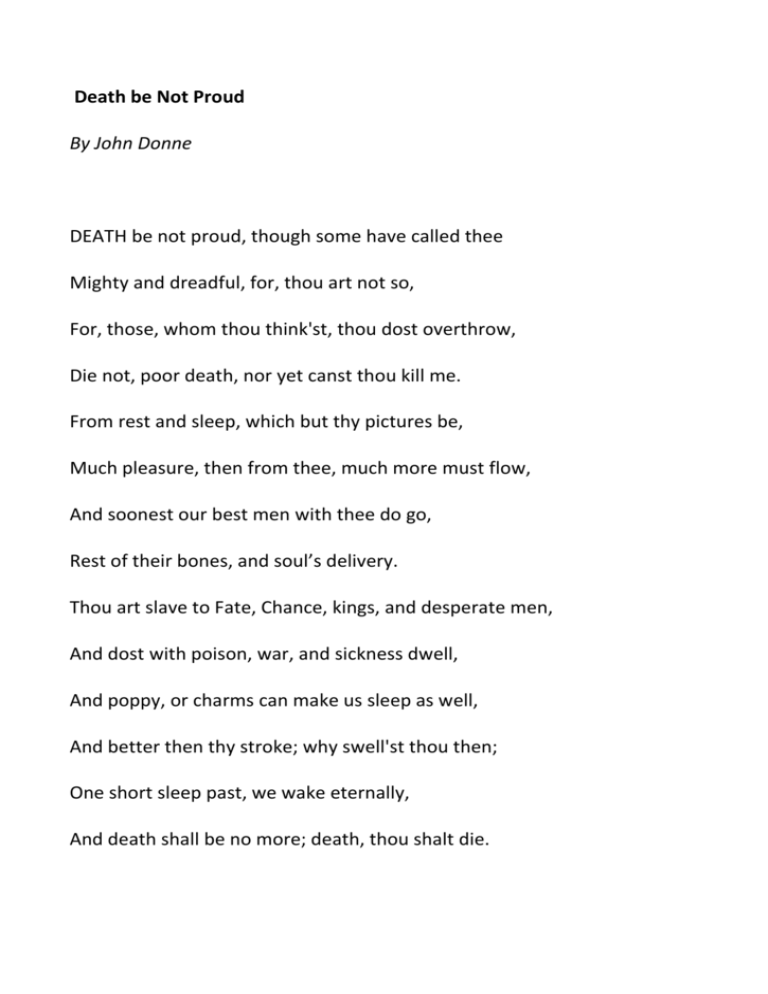

Death be Not Proud By John Donne DEATH be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for, thou art not so, For, those, whom thou think'st, thou dost overthrow, Die not, poor death, nor yet canst thou kill me. From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow, And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery. Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell, And poppy, or charms can make us sleep as well, And better then thy stroke; why swell'st thou then; One short sleep past, we wake eternally, And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die. Death, be not proud (Holy Sonnet 10) Summary Right off the bat, the speaker starts talking smack to Death, whom he treats as a person. He tells Death not to be so proud, because he’s really not as scary or powerful as most people think. The speaker startstalking in contradictions, saying that people don’t really die when they meet Death – and neither will the speaker. Then, he really tries to burn Death’s biscuit by comparing him to "rest and sleep," two things that aren’t scary at all. Next, to paraphrase Billy Joel, the speaker claims that "only the good die young," because the best people know that death brings pleasure, not pain. As if this isn’t enough trash-talk, the speaker kicks it up a notch, calling Death a "slave" and accusing him of hanging out with those lowlifes "poison, war, and sickness." Besides, we don’t need Death – the speaker can just take drugs, and it will have the same effect: falling asleep. So death is just a "short sleep," after which a good Christian will wake up and find himself in Eternity. Once this happens, it will seem like Death has died. How do you like them apples? Death, be not proud (Holy Sonnet 10): Rhyme, Form & Meter We’ll show you the poem’s blueprints, and we’ll listen for the music behind the words. Petrarchan Sonnet You can thank Petrarch for all the sonnets you have to read in school. This 14th century Italian poet isn’t the first person to write sonnets, but he makes the form popular all across Europe, including England. He is the Elvis Presley of the sonnet. But, just as with rock 'n' roll, new poets keep fiddling with the sonnet form, tweaking it slightly to fit their needs. Shakespeare, for example, uses a different form of the sonnet, which we call "Shakespearean" for that reason. But, Donne stuck to the original. Mostly. The Petrarchan sonnet has fourteen lines and a rhyme scheme that goes ABBAABBA and then, most frequently, CDCDCD. But, "Death, be not proud" finishes slightly differently. Its last six lines are CDDCAA. If you look closer, there’s even more weird stuff going on at the end. For example, line 13 has a word near the end, "swell’st," that rhymes with "dwell" and "well" from the previous two lines. He just sticks a rhyme in the middle of the verse: very strange. And, the last two lines don’t seem to rhyme well at all: "eternally" and "die." You have to pronounce it "eternal-lie" to make the rhyme work. No one is sure exactly what Renaissance English sounds like, so it’s possible that they did pronounce the word this way. But, it’s also possible that Donne wanted the rhyme scheme to fizzle out at the same moment when death "dies." Another feature of a Petrarchan sonnet is a shift, or "turn," in the argument or subject matter somewhere in the poem. In Italian, the word is volta. Usually, the turn occurs at line 9 to coincide with the introduction of a new rhyme scheme. That’s the case for "Death, be not proud," although the turn isn’t major. The speaker sharpens his attack and starts calling Death names, but he doesn’t fundamentally change his argument. If you want to rebel, you can argue that the real turn doesn’t happen until the middle of the last line, when Donne drops this shocker: "Death, thou shalt die." At the very least, we think it’s the most surprising move in the poem. Finally, the Petrarchan sonnet has a regular meter: iambic pentameter, which means that each line has ten syllables, and every second syllable is accented. That’s the reason, for example, that "Thou art" has to be condensed into one mouth-cramming syllable, "Thou’art" in line 9. Otherwise, there would be eleven syllables in the line. But, what about the first line? For one thing, it begins on an accented beat: DEATH. Truth be told, Donne’s pretty loose with his iambic pentameter. For him, iambic pentameter is less of a rule and more of a general guideline, like that "No Jumping" sign at your local pool. Of course there’s going to be jumping! It’s a pool! And Donne sometimes counts a big pause as a syllable, which is why line 1 seems to only have nine syllables: because of the pauses in the line, it takes at least as long to recite. Death, be not proud (Holy Sonnet 10) Trivia Brain Snacks: Tasty Tidbits of Knowledge Donne was "obsessed with the idea of death," and even posed for a painting wearing the same kind of cloth (a shroud) used to cover dead bodies. Kind of makes sense in the light of this poem, no? Donne converted from Roman Catholicism to Anglicanism, the semi-official religion of England. This was a big deal back in the Renaissance, when being Catholic in England could lead to persecution. Donne was considered one of the very best preachers of his day, and his sermons are first-rate. Despite this, he also wrote some sexually explicit poems that would make your mother blush bright red. Check out "The Flea," in which he describes his blood mingling with his lover’s inside, yes, a bug.