Dietary Supplement Safety Information in Magazines Popular

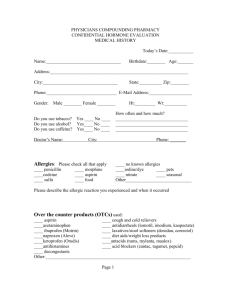

advertisement

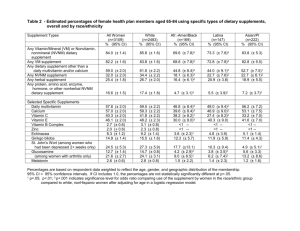

Journal of Health Communication, Volum e 7, pp. 13±23, 2002 Copyright # 2002 Taylor & Francis 1081-0730 /02 $12.0 0 + .00 Articles Dietary Supplement Safety Information in Magazines Popular among Older Readers RUTH KAVA KATHLEEN A. MEISTER ELIZABETH M. WHELAN ALICIA M. LUKACHKO CHRISTINA MIRABILE American Council on Science and Health New York, New York, USA Dietary supplements are extensively used in the United States, especially by people age 50 and over. Surveys have shown that magazines and other news media are an important source of information about nutrition and dietary supplements for the American public. It is uncertain, however, whether magazines provide their readers with adequate information about the safety aspects of supplement use. This report presents an analysis of supplement safety information in articles published during 1994–1998 in 10 major magazines popular among older readers. This time period was chosen to allow the impact of the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) to be assessed. The evaluation included 254 magazine articles. More than two-thirds of the articles did not include comprehensive information about the safety aspects of the dietary supplements that were discussed. Information about safety issues such as maximum safe doses and drug–supplement interactions was often lacking even in otherwise informative and well-researched articles. A total of 2,983 advertisements for more than 130 different types of supplements were published in the magazines surveyed. The number of advertisements per year increased between 1995 and 1998. Supplements of particular interest to older adults (such as antioxidants, calcium, garlic, ginkgo biloba, joint health products, liquid oral supplements, and multivitamins) were among the most frequently advertised products. Although magazines popular among older readers contain extensive information about dietary supplements, these publications cannot be relied upon to provide readers with all of the information that they need in order to use supplements safely. Recent surveys indicate that at least 40% of American adults take dietary supplements (American Dietetic Association [ADA], 2000b; Balluz, Kieszak, Philen, & Mulinare, 2000; Eliason, Myszkowski, Marbella, & Rasman, 1996; Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 1999; Hensrud, Engle, & Scheitel, 1999; Phillips & Osborne, 2000). Vitamins This project was supported by a grant to the American Counci l on Science and Health from the Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation , Inc. Address correspondence to Ruth Kava, Ph.D., R.D., Director of Nutrition , American Council on Science and Health, 1995 Broadway, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10023, USA. E-mail: kava@acsh.or g 13 14 R. Kava et al. and minerals are the most popular types of dietary supplements, but sales of herbal supplements and other nonvitamin±nonmineral supplements have increased substantially during the past decade (FDA, 1999). People in their ®fties or older are more likely than younger adults to use dietary supplements (ADA, 2000b; Balluz et al., 2000; Slesinski, Subar, & Kahle, 1995). For example, in one recent survey, daily supplement use was reported by 65% of respondents age 55 and over, as compared with 47 % of those aged 35 to 54 and 35% of those aged 25 to 34 (ADA, 2000b). Among older people, women are more likely to use supplements than men, and Whites use supplements more frequently than African Americans (Gray, Hanlon, Fillenbaum, Wall, & Bales, 1996; Kava, Whelan, & Meister, 2001). The use of dietary supplements may be bene®cial to health for some older adults. For example, the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences has speci®cally recommended that people age 50 and over meet most of their need for vitamin B 12 by consuming supplements or forti®ed foods (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 1998). Because vitamin D de®ciency is common among older people, some experts recommend that all older adults should routinely take supplements of this vitamin (Compston, 1998; Utiger, 1998). The use of multivita min = mineral supplements may be advisable for older people who eat a limited variety of foods (ADA, 2000a). On the other hand, dietary supplements can also pose health hazards under some circumst ances. Excessive doses of some vitamins and minerals, such as vitamins A, B 6 , and D, and niacin, selenium, and iron, can have serious toxic effects (ADA, 1996). Some herbal supplements, including chaparral, comfrey, ephedra (ma huang), germander, lobelia, and yohimbe, also have the potential for serious toxicity (FDA, 1993; Haller & Benowitz, 2000). Some dietary supplements may be of poor quality; independent analyses have shown that some products do not contain the amounts of ingredients stated on their labels (Consumers Union, 1995; Cui, Garle, Eneroth, & Bjorkhem, 1994; Gurley, Gardner, & Hubbard, 2000; Heptinstall et al., 1992) and that some contain undesirable (in some cases, even potentially toxic) contaminants (Ko, 1998; Ross, Szabo, & Tebbett, 2000; Slifman et al., 1998). Some dietary supplements are contraindicated for individuals with speci®c chronic health problems (Cupp, 1999), and some may interact with prescription medications or complicate surgery (Ang-Lee, Moss, & Yuan, 2001; Cupp, 1999; Fugh-Berman, 2000; Heck, DeWitt, & Lukes, 2000; Henney, 2000; Miller, 1998). The risk of drug±supplement interactions is especially high among the older population because older people take more medications than younger people do. Although people over the age of 65 make up only about 13 % of the total population (Administration on Aging, 1999), they use about 30 % of all prescription drugs (W illiams, 1997). More than half of all older adults in the United States who are taking prescription drugs to treat chronic health problems also take dietary supplements (Kava et al., 2001). Consumers sometimes assume that all health-related products must be approved by the government before they are placed on the market. In the case of dietary supplements, however, this assumption is false. Most dietary supplements do not need to be approved by FDA before they are sold. The unusual regulatory status of dietary supplements is a result of the DSHEA, which was passed by Congress in 1994. This law created a new framework for the regulation of dietary supplements, expanded the meaning of ``dietary supplement’’ to include herbs and other substances as well as essential nutrients, and exempted most ingredients in dietary supplements from premarket safety evaluation (FDA, 1995; Kurtzweil, 1998). Because the government’s role in assuring the safety of dietary supplements is limited, much of the responsibility for making sure that these products are used safely lies with manufacturers and consumers (Kurtzweil, 1998). Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online Dietary Supplement Safety Information 15 Magazines and other news media are an important source of information about nutrition and dietary supplements for the American public. In a recent national survey (ADA, 2000b), 48 % of respondents cited television as one of their top sources of nutrition information, 47 % cited magazines, and 18 % cited newspapers. In another national survey, 37 % of supplement users age 50 and over said that ``ads or articles’’ were their source of information about the supplements they were currently taking (Kava et al., 2001). To ®nd out what kind of information about dietary supplement safety older adults may obtain from popular magazines, the authors conducted a content analysis of information about supplements presented in articles published in 10 major magazines popular among older readers. The analysis focused on safety rather than ef®cacy, because currently there is no legal basis upon which the ef®cacy of supplements can be evaluated. Magazine articles were categorized according to a three-point scale based on whether they included full, accurate information on each of ®ve points crucial for the safe use of dietary supplements. The authors also examined advertisements published in the same magazines in order to ®nd out what types of supplements were being promoted to the older consumer and whether changes had occurred in supplement advertising patterns during the period of the study. Since advertisements for dietary supplements usually do not include safety information, the authors did not conduct a content analysis of the advertisements. Methods Magazine Selection The criteria for magazine selection were (1) median age of readers greater than or equal to 42 years (Kelly, 1997); (2) presence in the top 200 circulating magazines (Kelly, 1997); and (3) diversity of usual subject matter. The magazines surveyed included one weekly news magazine ( Newsweek), one general interest magazine ( Reader’s Digest), two magazines that dealt with a variety of topics of interest primarily to older readers ( Modern Maturity and New Choices), three magazines dealing primarily with health and nutrition topics ( American Health for Women, Health, and Prevention ), and three magazines that cover home and health topics ( Better Homes and Gardens, Good Housekeeping , and Ladies’ Home Journal). Article Selection Magazines were searched for appropriate articles for 1994±1998, inclusive. This period of time was chosen in order to allow the impact of DSHEA, which was passed in 1994, to be assessed. Articles selected were at least one-half of a printed page (approximately 400 words) long. Dietary supplements did not have to be the primary focus of a selected article, but they did have to be at least mentioned in a context that might prompt a reader to become interested in using them. For example, an article about heart disease might mention that some people take vitamin E to prevent heart disease. The article might or might not give further information about the ef®cacy or safety of vitamin E, but the reader could be led to assume that this is a safe way to help prevent heart disease. Such an article would be included in the study. Six of the selected magazines ( American Health for Women, Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, Modern Maturity, Newsweek, and Prevention ) are indexed by the Lexis-Nexis database; searches were performed using the following key words: nutrition, Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online R. Kava et al. 16 supplement, diet, dietary, herbal, mineral, vitamin. For each year included in the survey, all articles found by the search were sequentially numbered, and up to 10 were selected from each magazine with a random number generator. Selected articles were printed and numbered in random order. Articles from magazines not indexed by Lexis-Nexis were selected from library copies; they were numbered, and if there were more than 10 in any year, were randomly selected. Article Evaluation Each article selected was independently evaluated by two judges, each of whom had a background in nutrition and = or public health. Article content as a whole was not evaluated; instead, information about the safety of dietary supplements mentioned or discussed was judged on a three-point scale. The criteria for rating were as follows: 1. Excellent: includes at least four of the following safety-related points about supplements if applicable: * the loose regulation of dietary supplements (including lack of regulation of quality), * the possibility of toxicity = overdose (when applicable), * the possibility of drug = supplement interactions, * the need for supplement users to notify their health care providers about any supplements that they are taking, * the lack of solid scienti®c information about the safety of many supplements (other than commonly consumed vitamins and minerals). 2. Good: mentions some safety points (especially toxicity = overdose and drug/supplement interactions, when applicable), but does not include as many of these points as would be found in an ``excellent’’ article. 3. Poor: contains exaggerated claims, and = or little, if any, safety information and= or includes inaccurate or misleading information or information not based on sound science. W hen the two judges disagreed on how to classify an article, the average of their two ratings was used. Advertisement Enumeration All advertisements for dietary supplements in each magazine included in the article evaluation were identi®ed and tabulated. Both display and classi®ed advertisements were included. If an advertisement mentioned more than one type of supplement, each type was counted as though it were a separate advertisement. Many of the products advertised included more than one ingredient. Such products were classi®ed by their principal ingredient or by their apparent use (e.g., antioxidant, menopause product, weight loss product) if no single principal ingredient could be identi®ed. Results Magazine Articles Two hundred ®fty-four magazine articles were evaluated. Of these, 40 (16 % ) were rated ``excellent’’ (1 or 1.5), 133 (52 % ) were rated ``good’’ ( > 1.5 but < 3), and 81 (32% ) were rated ``poor’’ (3). Table 1 shows the results for individual magazines. No more than Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online 17 American Health for Women Better Homes and Gardens Good Housekeeping Health Ladies’ Home Journal Modern Maturity New Choices Newsweek Prevention Reader’s Digest Magazine Number 5 4 7 9 2 1 0 2 7 3 Total Articles 25 28 27 43 9 3 21 27 49 22 20 14 26 21 22 33 0 7 14 14 Percent Excellent (1 or 1.5) 13 15 8 28 5 1 8 15 27 13 Number 52 54 30 65 56 33 38 56 55 59 Percent Good ( > 1.5 but < 3) Poor (3) 7 9 12 6 2 1 13 10 15 6 Number TABLE 1 Number and Percentage of Articles Rated Excellent, Good, or Poor in Each Magazine Surveyed (1994±1998) 28 32 44 14 22 33 62 37 31 27 Percent R. Kava et al. 18 one-third of the articles in any magazine were rated ``excellent.’’ The ®ve magazines with the highest proportion of ``excellent’’ ratings (20 % or more) were American Health for Women, Good Housekeeping, Health, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Modern Maturity. The magazine with the poorest ratings was New Choices . This magazine had no ``excellent’’ articles, and it was the only one in which more than half of all articles were rated ``poor.’’ The average article ratings for all magazines were between 2 (``good’’) and 3 (``poor’’), as shown in Figure 1, with no noticeable time trends over the ®ve years of the study. Overall, the amount and quality of supplement safety information presented in the magazine articles varied greatly, with most articles presenting only partial information, if any. In many instances, information about supplement safety issues was lacking even in articles that were balanced and informative in other respects. For example, several articles on bone health presented accurate, well-resea rched information on the potential bene®ts of calcium and vitamin D supplements in the prevention of osteoporosis. However, some of these articles failed to mention that calcium supplements can interfere with the absorption of some types of medication (IOM, 1997) or that excessive doses of vitamin D can be toxic (IOM, 1997). Similarly, several articles reported, accurately, that the potential bene®ts of ginkgo biloba as a memory aid have neither been proven nor disproven. However, some of these articles did not mention the important fact that ginkgo biloba interacts with anticoagulant drugs in a way that can promote dangerous bleeding (Cupp, 1999). Advertisements A total of 2,983 advertisements for dietary supplements were identi®ed in the magazines. More than 130 different types of supplements were advertised. The total number of supplement advertisements appearing in the 10 magazines decreased from 1994 to 1995 and then increased each year thereafter, as shown in Table 2. Four of the individual magazines ( Ladies’ Home Journal, New Choices, Prevention, Reader’s Digest) also showed increases in the number of supplement advertisements published during these years. During the ®ve-year period of the study, three magazines carried large numbers of supplement advertisements ( Prevention , 937; American Health for Women, 757; New Choices, 415); three others carried intermediate numbers of advertisements ( Health, 281; Reader’s Digest, 223; Ladies’ Home Journal, 165), and the other four carried relatively few supplement advertisements ( Better Homes and Gardens, 88; Modern Maturity, 58; Good Housekeeping, 41; Newsweek, 18). No relations hip was found between the number of supplement advertisements appearing in various magazines and the quality of the supplement safety information presented in articles in the same magazine. Of four major categories of supplements (vitamins, minerals, herbs, and hormones), vitamins were the type most frequently advertised in four of the magazines ( Better Homes and Gardens, Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Newsweek). Herbs were the most frequently advertised category in the other six magazines ( American Health for Women, Health, Modern Maturity, New Choices, Prevention, and Reader’s Digest). Multivitamins (227 ads) and antioxidants (107 ads) were the most frequently advertised vitamin products; calcium (176 ads) was the most frequently advertised mineral; ginkgo biloba (126 ads), garlic (120 ads), and ginseng (98 ads) were the most frequently advertised herbs; and melatonin (58 ads) was the most frequently advertised hormone. Of products that did not ®t into any of these categories, the two most heavily advertised types were liquid oral supplements (meal replacers; 163 ads) and various products Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online FIGURE 1 Average magazine article ratings, 1994±98. 19 Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online R. Kava et al. 20 TABLE 2 Number of Supplement Advertisem ents, 1994±1998 Magazin e 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 Total American Health for Women Better Homes and Gardens Good Housekeeping Health Ladies’ Home Journal Modern Maturity New Choices Newsweek Prevention Reader’s Digest 153 29 10 90 19 7 20 5 150 33 96 9 12 41 8 13 25 1 161 22 202 9 6 47 29 17 53 4 182 32 162 24 4 48 39 16 149 5 212 60 144 17 9 55 70 5 168 3 232 76 757 88 41 281 165 58 415 18 937 223 Total 516 388 581 719 779 2,983 promoted for their effects on joint health (such as glucosamine, chondroitin, and a gelatine = vitamin C = calcium combination product; 115 ads). Discussion The results of this analysis show that magazines popular among older readers contain an abundance of information on dietary supplements, both in articles and in advertisements. However, readers cannot count on these publications to provide them with the information that they need in order to use supplements safely. Advertisements for dietary supplements usually do not include safety information, and, as our results show, most magazine articles that mention or discuss dietary supplements do not provide comprehensive information on the safety aspects of these products. It is likely that the passage of DSHEA in 1994 was one of the factors responsible for the increase in the number of magazine advertisements for supplements in subsequent years. However, no correlative trend was evident between the passage of DSHEA and the amount of supplement safety information presented in magazine articles. The reason(s) for the dearth of safety information about dietary supplements in popular magazine articles cannot be determined from our data. One may speculate about whether the lack was due to editorial policy or to the lack of information on the part of authors. Information about potential safety problems related to some vitamin and mineral supplements (National Research Council, 1989) as well as herbal supplements (Tyler, 1993) has been available for many years, although perhaps not as readily available as it is currently. Still, it is dif®cult for consumers to ®nd accurate information about the safety of dietary supplements. As pointed out in a July 2000 report by the General Accounting Of®ce (GAO), some dietary supplement products do not have safety-re lated information on their labels. According to the GAO, there is a legal basis that would allow the FDA to require supplement manufacturers to provide information about safety issues (such as maximum safe dosages and possible interactions between product ingredients and drugs). However, the agency has not yet developed regulations of this type or provided guidance to industry on the type of safety information that should be included on supplement labels. Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online Dietary Supplement Safety Information 21 Health professionals are another possible source of supplement safety information, but many consumers do not take advantage of this resource. Several surveys have shown that the majority of people who use dietary supplements or other forms of alternative therapy do not inform their physicians or pharmacists (Bennett & Brown, 2000; Blendon, DesRoches, Benson, Brodie, & Altman, 2001; Eisenberg et al., 1998; Foster, Phillips, Hamel, & Eisenberg, 2000; Hensrud, Engle, & Scheitel, 1999). In two recent surveys, respondents said that they do not discuss the use of dietary supplements with their physicians because they believe that the physicians have little knowledge about these products and may be biased against them (Blendon et al., 2001; Eliason, Huebner, and Marchand, 1999). Other factors that may contribute to patients’ failure to disclose supplement use include the patients’ view that these products are not ``medications’’ (Fessenden, W ittenborn, & Clarke, 2001) and the mistaken belief that supplements must be safe because they are ``natural’’ (Bauer, 2000). Even if patients do reveal their use of supplements, some health professionals may not know enough about these products to counsel patients adequately. Good scienti®c information about many dietary supplements and other forms of alternative therapy is lacking (Eisenberg, 1997; Miller et al., 2000), and the curricula of schools of medicine (W etzel, Eisenberg, & Kaptchuk, 1998) and pharmacy (Miller et al., 2000) do not necessarily include instruction about herbal supplements and other forms of complementary medicine. One recent survey of pharmacists in Virginia and North Carolina showed that most could not correctly answer questions about the safety aspects of herbal supplements (such as drug interactions, adverse effects, and precautions; Chang, Kennedy, Holdford, & Small, 2000). A survey of licensed dietitians in Oregon showed that fewer than 10 % considered themselves knowledgeable about herbal supplements (the dietitians did, however, consider themselves knowledgeable about nutrient supplements; Lee, Georgion, & Raab, 2000). An organized effort to provide American consumers with systematic information about the safety of dietary supplements is urgently needed. Better labeling of these products would be a step in the right direction, and the increased availability of continuing education programs about dietary supplements for health professionals would also be helpful. At the present time, however, people who use dietary supplements have to piece together information from a variety of sources in order to learn the facts that they need to use these products safely. It would be unwise for people to rely on articles in magazines as their sole guide to supplement safety, because the information provided by these articles may be inaccurate or incomplete. References Administration on Aging. (1999) . Pro le of Older Americans: 1999. Washington, DC: Administration on Aging and AARP. [On-line]. Available: http: == www.aoa.gov = aoa = STATS= pro®le = default.htm American Dietetic Association (ADA). (1996). Vitamin and mineral supplementationÐPosition of the American Dietetic Association. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 96, 73±77. American Dietetic Association (ADA). (2000a). Nutrition, aging, and the continuu m of careÐ Position of the American Dietetic Association. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100, 580±595. American Dietetic Association (ADA). (2000b) . Nutrition and you: Trends 2000. Chicago, IL: Author. Ang-Lee, M. K., Moss, J., & Yuan, C. S. (2001). Herbal medicines and perioperativ e care. Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 208±216. Balluz, L. S., Kieszak, S. M., Philen, R. M., & Mulinare, J. (2000) . Vitamin and mineral supplement use in the United States. Archives of Family Medicine, 9, 258±262. Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online 22 R. Kava et al. Bauer, B. A. (2000) . Herbal therapy: What a clinician needs to know to counsel patients effectively . Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 75, 835±841. Bennett, J., & Brown, C. M. (2000) . Use of herbal remedies by patients in a health maintenanc e organization. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, 40, 353±358. Blendon, R. J., DesRoches, C. M., Benson, J. M., Brodie, M., & Altman, D. E. (2001) . Americans’ views on the use and regulatio n of dietary supplements. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161, 805±810. Chang, Z. G., Kennedy , D. T., Holdford, D. A., & Small, R. E. (2000) . Pharmacists’ knowledg e and attitudes toward herbal medicine. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 34, 710±715. Compston, J. E. (1998). Vitamin D de®ciency: Time for action. British Medical Journal, 317, 1466± 1467. Consumers Union. (1995). Herbal roulette . Consumer Reports, 60, 698±705. Cui, J., Garle, M., Eneroth, P., & Bjorkhem , I. (1994). What do commercial ginseng preparation s contain? Lancet, 344, 134. Cupp, M. J. (1999). Herbal remedies: Adverse effects and drug interactions . American Family Physician, 59, 1239±1244. Eisenberg, D. M. (1997) . Advising patients who seek alternativ e medical therapies . Annals of Internal Medicine, 127, 61±69. Eisenberg, D. M., Davis, R. B., Ettner, S. L., Appel, S., Wilkey, S., Van Rompay, M., & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990±1997: Results of a follow-up nationa l survey. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 1569± 1575. Eliason, B. C., Huebner, J., & Marchand , L. (1999) . What physician s can learn from consumers of dietary supplements. Journal of Family Practice, 48, 459±463. Eliason, B. C., Myszkowski, J., Marbella, A., & Rasmann, D. N. (1996). Use of dietary supplements by patients in a family practice clinic. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 9, 249±253. Fessenden, J. M., Wittenborn, W., & Clarke, L. (2001) . Gingko biloba: A case report of herbal medicine and bleeding postoperativel y from a laparoscopic cholecystecto my. The American Surgeon, 67, 33±35. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (1993) . Illnesses and injuries associated with the use of selected dietary supplements [On-line] . Available : http:== vm.cfsan.fda.go v = ¹ dms= dsill.htm l Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (1995). Dietary supplement health and education act of 1994. [On-line]. Available : http: == vm.cfsan.fda.g ov = ¹ dms = dietsupp.html Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (1999) . Economic characterization of the dietary supplement industry: Final report. Washington, DC: Author. [On-line]. Available : http:== vm.cfsan. fda.gov = ¹ comm = ds-econt.html Foster, D. F., Phillips, R. S., Hamel, M. B., & Eisenberg, D.M. (2000) . Alternativ e medicine use in older Americans. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 48, 1560±1565. Fugh-Berman, A. (2000). Herb-dru g interactions . Lancet, 355, 134±138. General Accounting Of®ce. (2000) . Improvements needed in overseeing the safety of dietary supplements and ‘‘functional foods.’’ GPO publicatio n GAO = RCED-00-156, Washington, DC: Author. Gray, S. L., Hanlon, J. T., Fillenbaum , G. G., Wall, W. E., Jr., & Bales, C. (1996). Predictors of nutritiona l supplement use by the elderly. Pharmacotherapy, 16, 715±720. Gurley, B. J., Gardner, S. F., & Hubbard, M. A. (2000). Content versus label claims in ephedracontainin g dietary supplements. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 57, 963±969. Haller, C. A., & Benowitz, N. L. (2000) . Adverse cardiovascula r and central nervou s system events associated with dietary supplements containin g ephedra alkaloids. New England Journal of Medicine , 343, 1833±1838. Heck, A. M., DeWitt, B. A., & Lukes, A. L. (2000) . Potential interaction s between alternativ e therapies and warfarin. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 57, 1221±1230. Henney, J. E. (2000). Risk of drug interaction s with St. John’s wort. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283, 1679. Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online Dietary Supplement Safety Information 23 Hensrud, D. D., Engle, D. D., & Scheitel, S. M. (1999). Underreportin g the use of dietary supplements and nonprescriptio n medication s among patients undergoin g a periodic health examination. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 74, 443±447. Heptinstall, S., Awang, D. V., Dawson, B. A., Kindrack, D., Knight, D. W., & May, J. (1992). Parthenolid e content and bioactivit y of feverfe w (Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Schutz-Bip.) : Estimation of commercial and authenticate d feverfe w products. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 44, 391±395. Institute of Medicine . (1997). Dietary reference intakes: Calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and uoride. Washington , DC: National Academy Press. Institute of Medicine. (1998). Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, ribo avin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. Washington , DC: National Academy Press. Kava, R., Whelan, E. M., & Meister, K. A. (2001). Dietary supplement use and the potential for drug-supple ment interaction s among older Americans. Manuscript submitted for publication . Kelly, K. J. (1997) . Consumer magazine paid circulation . Advertising Age, 68(8), 14. Ko, R. J. (1998). Adulterants in Asian patent medicines . New England Journal of Medicine, 339, 847. Kurtzweil, P. (1998) . An FDA guide to dietary supplements. FDA Consumer, 32(5), 28±35. Lee, Y. K., Georgion , C., & Raab, C. (2000). The knowledge , attitudes , and practice s of dietitian s licensed in Oregon regardin g functiona l foods, nutrient supplements, and herbs as complementary medicine. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100, 543±548. Miller, L. G. (1998). Herbal medicinals . Selected clinical consideration s focusing on known or potentia l drug-her b interactions . Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 2200±2211. Miller, L. G., Hume, A., Harris, I. M., Jackson, E. A., Kanmaz, T. J., Cauf®eld, J. S., Chin, T. W., & Knell, M. (2000) . White paper on herbal products: American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy, 20, 877±891. National Research Council. (1989). Recommended dietary allowances (10th ed.). Washington , DC: National Academy Press. Phillips, A. W., & Osborne, J. A. (2000) . Survey of alternativ e and nonprescriptio n therapy use. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 57, 1361±1362. Ross, E. A., Szabo, N. J., & Tebbett, I. R. (2000). Lead content of calcium supplements . Journal of the American Medical Association, 284, 1425±1429. Slesinski, M. J., Subar, A., & Kahle, L. (1995). Trends in the use of vitamin and mineral supplements in the United States: The 1987 and 1992 National Health Interview Surveys. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 95, 921±923. Slifman, N. R., Obermeyer, W. R., Aloi, B. K., Musser, S. M., Correll, W. A., Jr., Cichowicz, S. M., Betz, J. M., & Love, L. A. (1998). Contamination of botanica l dietary supplements by Digitalis lanata. New England Journal of Medicine, 339, 806±811. Tyler, V. E. (1993). The honest herbal (3rd ed.). New York: Haworth Press, Inc. Utiger, R. D. (1998). The need for more vitamin D. New England Journal of Medicine, 338, 828± 829. Wetzel, M. S., Eisenberg, D. M., & Kaptchuk , T. J. (1998). Courses involvin g complementa ry and alternativ e medicine at US medical schools. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 784±787. Williams, R. D. (1997) . Medication and older adults. FDA Consumer, 31(6), 15±19. Click here to access the Journal of Health Communication Online