The Next Number: Extending Triads to Seventh

advertisement

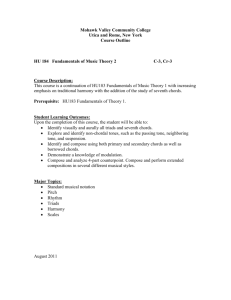

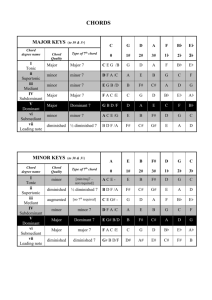

The Next Number: Extending Triads to Seventh Chords Copyright © 2012, Erik Hoffman erik@erikhoffman.com When we start learning about chords, we talk the most basic chord: the Triad. We learn Root – 3rd – 5th. And within this structure there’s a lot to learn. One of the things we learn is to classify chords. At the most basic, we learn about major and minor. Music theory books expand this classification into for “chord qualities”: There are four triad qualities: 1) 2) 3) 4) Major Minor Diminished Augmented Each of these chord qualities has its own particular sound. If you can find a piano, you can hear the first three of these qualities by building triads on the white keys. Play three notes like this: play a note, skip the next, play the next, skip the next, and play the third. Starting on a C note, you’ll end up playing C – E – G, a C major chord. Sticking to the white keys will yield: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) a C Major triad (C – E – G) a D Minor triad (D – F – A) an E Minor triad (E – G – B) an F Major triad (F – A – C) a G Major triad (G – B – D) an A Minor triad (A – C – E) and a B diminished triad (B – D – F) Recall from the last “dissertation” that these chords are built by stacking thirds. 3‐half‐steps is a minor 3rd, 4‐ half‐steps a major 3rd. That is, it’s a 3rd from C to E, and a 3rd from E to G. The major chord is made by having the 3rd between the Root and 3rd (sorry about the changing references in numbers) is a major 3rd. The 3rd between the 3rd and 5th is a minor. To build a minor, the major/minor order is reversed. To build the diminished, both are minor, and to build an augmented, both are major. There are no “naturally occurring” augmented chords in that you can build using just the notes of a major scale. Thus to build an Augmented Triad, we need to venture out of the key. Example: C Aug is C – E – G#. Building the 7th Chord: If we stack one more third on top of the triad, we get a 7th chord. 7th chords also have Qualities, and their names vary a bit depending on if you’re using “harmonic analysis speak,” or “jazz speak,” or “folk speak.” I’m using “harmonic analysis” talk: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) Major 7 Minor 7 Dominant 7 Half Diminished 7 Fully Diminished 7 Minor with a Major 7 For our purposes, we start with the first three. Recently, we went through the triads that were built in a scale. We made that chart. The D one looked (in part) like this: D or I Em or ii F#m or iii G or IV Etc. R – D D Etc. 2 – E E Etc. 3 – F# F# F# 4 – G G G 5 – A A A 6 – B B B 7 – C# C# 8/1 – D D 9/2 – E We discussed “stacking thirds” and counting half steps. We said, “from D to F# is 4 half‐steps, a major 3rd.” And, “from F# to A is 3 half‐steps, an minor third.” We even said (I think), “from D to A is 7 half‐steps, a ‘Perfect 5th.’” Now we take it one step further: we add the seventh of the chord by stacking one more third: D Maj 7 Em7 F#m7 GMaj7 A7 R – D 2 – E 3 – F# 4 – G 5 – A 6 – B 7 – C# 8/1 – D 9/2 – E 3 – F# 4 ‐ G D E F# F# G G A A A B B C# C# C# D D E E F# G I leave it to you to finish the chart, but by now you should see the pattern. Here we say we’re playing the Root (or the 1 or the “tonic”), 3, 5, & 7 of the chord. If we look at the G chord, the Root is G, the 3rd is B, the 5th is D, and the 7th is F#. And, again we count half steps and notice whether the Root triad is major or minor. We could count half‐steps from the 5th to the 7th. Again, taking G as an example, we count 4 half‐steps from D to F# (a major 3rd). We also notice that from F# to G is only 1 half‐step, or 11 half‐steps from the lower Root. This interval is called a major 7. Notice that this major 7th is also present in the D chord with its added 7. That is to say, the 7th chord that occurs with D as it’s root is a major triad and a major 7th, and we call it a D major seventh. If we look at the 7th chord built on E, F#, and B in the key of D we come up with: E – G – B – D F# – A – C# – E B – D – F# – A All three of these have a minor triad at their roots, and a minor 3rd from the 5th to the 7th. Another way to note the 7th is that it’s a whole step below the octave of the root. We call this chord a minor seventh. Note that the chords built on the Root (D) and the 4 (G) are both major seventh chords. The chords built on the 2 (E), 3 (F#), and 6 (B) are all minor seventh chords. The seventh chords built on the 5 (A) and the 7 (C#) are both unique. The seventh built on the 5, in the key of D, the A7 chord is extremely important. The chord built on the C# is not so important to us at this time. So, let’s look at the A7 chord. The notes in the A7 chord are: A – C# – E – G The Root chord is a major triad, but the 7th is a “minor 7” or a whole step below the octave of the root. This quality of a major triad, with the flatted 7th has a particular quality, a tension, or dissonance, that our ears want to resolve. It wants us to return to the Root chord (in this case, D). In the folk and jazz world, we call this a Seventh Chord. This distinguishes it from the minor 7th, and the major 7th. It is also often called a “Dominant Seveth,” which comes from the harmonic analysis world. But that name is used often enough to make it worth knowing. Again, note, when building the seventh chords from the notes in a major key, we get two major seventh chords, built on the Root and the 4 notes; three minor seventh chords, built on the 2, 3, and 6 notes, one “dominant 7,” or just plain “7” chord, built on the 5 note; and an extremely odd chord built on the 7 note. It hasn’t been discussed, but it is a minor 7 flat 5, or m7b5, or “half‐diminished” chord. (In the key of D, it’s a C#m7b5). A lot of words to describe a quality our ears perceive. The best thing to do now is to play these chords while listening to their quality. You can do this by playing arpeggios, or play them on a piano, or get a friend to play them on a chordal instrument. Or get me to play them in class…