notesontheprogram - New York Philharmonic

advertisement

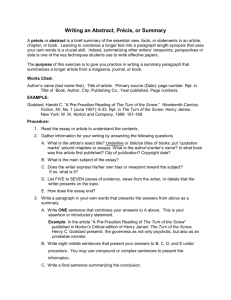

04-22 Gershwin_Layout 1 4/3/14 11:03 AM Page 25 NOTESONTHEPROGRAM BY JAMES M. KELLER, PROGRAM ANNOTATOR The Leni and Peter May Chair Overture to Candide Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Leonard Bernstein he story of Leonard Bernstein’s musical comedy — or operetta, or opera — Candide is convoluted and, in the end, not altogether happy, an unfortunate situation for an ebullient, madcap work whose Overture positively sparkles. Voltaire is ultimately to blame for the whole affair, since it was his novella Candide, ou L’Optimisme (1759) that inspired Bernstein to struggle for more than three decades to find the perfect way to translate it for the musical stage. To Voltaire we owe the tale of the wideeyed hero Candide, whose travels to distant points of the globe invariably turn into dismal misadventures, much though he may be assured by his idealistic tutor, Doctor Pangloss, that everything is for the best. Voltaire wrote his novella as a charming and persuasive rebuttal to the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibnitz’s metaphysical assertion that “All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.” This struck Voltaire as palpably absurd. What about blatant violence, Voltaire asked. What about shipwrecks? What about the Spanish Inquisition? Candide has to deal with them all in the course of this tale, and by the time he gets back to his native Westphalia he has become a wiser, if more cynical, young man, intent on finding happiness where he can, content in just making his garden grow. In the fall of 1953, author Lillian Hellman suggested teaming up with Bernstein to develop a stage work based on Candide. By January 1954, Bernstein was firmly committed to T IN SHORT Born: August 25, 1918, in Lawrence, Massachusetts Died: October 14, 1990, in New York City Works composed and premiered: Candide was composed 1954–56, with Hershy Kay assisting with the orchestration; and frequently revised; previews began October 29, 1956, at the Colonial Theatre in Boston; the show opened on Broadway at the Martin Beck Theatre on December 1 of that year. West Side Story was composed 1955–57; Bernstein assembled the Symphonic Dances in 1961, overseeing orchestration carried out by Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal; dedicated “To Sid Ramin, in friendship”; West Side Story was premiered on August 19, 1957, at the National Theatre in Washington, D.C; Symphonic Dances was premiered on February 13, 1961, with Lukas Foss conducting the New York Philharmonic. New York Philharmonic premieres and most recent performances: Overture to Candide premiered January 26, 1957, with the composer conducting; most recently performed May 23, 2013, Case Scaglione, conductor. Symphonic Dances from West Side Story most recently played February 18, 2014, in Taipei, Taiwan, Alan Gilbert, conductor Estimated durations: Overture to Candide, ca. 5 minutes; Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, ca. 24 minutes APRIL 2014 | 25 04-22 Gershwin_Layout 1 4/3/14 11:03 AM Page 26 the project, which he initially envisioned as a full-scale, three-act opera. Hellman began fashioning Voltaire’s volume into a book for the show, and John Latouche and Richard Wilbur were enlisted to pen the lyrics, although Hellman, Dorothy Parker, and Bernstein himself all contributed to the script. Candide opened in New York on December 1, 1956, and played for 73 performances at the Martin Beck Theatre — long enough to have proved in some measure respectable (and certainly long enough to pique the interest of many sophisticated music lovers), but not long enough to be considered a success by any stretch of Broadway’s imagination. In the course of later emendations Candide was transformed considerably. Hellman did not allow her book to be used for the 1973 version staged by Hal Prince at the Chelsea Theatre Center, so on that occasion a new libretto, reduced to a single act from the original two, was created by Hugh Wheeler, with Stephen Sondheim joining Wilbur, Latouche, and Bernstein on the list of the show’s lyricists. Unfortunately, some marvelous musical numbers needed to be omitted for that incarnation of the show. Permutations, combinations, and revisions of either or both of those two versions continued through Candide’s uncertain history, some emphasizing the score’s operatic elements, others its musical comedy streak. Bernstein was directly involved in at least seven versions of Candide, none of which proved definitive, although each had his blessing, at least provisionally. In 1989 the composer led a concert performance in London — in a version happily preserved on recordings — that stands as his last sign-off on the theatrical work that had eluded him for 33 years. Through all the turmoil, Candide’s Overture remained essentially untouched. Why change it? From the outset it was a popular, perfect piece of bubbling optimism and knowing skepticism. At least in this Overture Bernstein achieved the flavor he seems to have sought for the rest of the piece. In the course of 1956 Bernstein scaled up the Overture‘s orchestration for a full symphony orchestra, and in this guise he introduced it as a stand-alone work with the New York Connecting Overture to Opera Bernstein’s Candide Overture prefigures the show by drawing principally on two vocal melodies that are prominent in the stage work. Following some can-can material and a theme that, in the show, occurs at the destruction of Candide’s native Westphalia, we hear a tender (though swiftly flowing) tune that will later resurface as the love duet “O Happy We,” sung by Candide and his girlfriend, Cunegonde. Bernstein had originally intended “O Happy We” as a duet for the characters of Tony and Maria to sing in another show/operetta/opera that was gestating at the same time — but West Side Story is a different story altogether. Near the Overture’s end, after many a musical joke, Bernstein tips his hat to Rossini and has the orchestra repeat over and over, louder and louder, a little tune extracted from Cunegonde’s aria “Glitter and Be Gay.” Kristin Chenoweth (left), as Cunegonde, and Patti LuPone, as The Old Lady, in the Philharmonic’s 2004 staged production of Candide 26 | NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 04-22 Gershwin_Layout 1 4/3/14 11:03 AM Page 27 Philharmonic on January 26, 1957. Within two years it would be played by almost 100 orchestras, rapidly becoming his most frequently performed symphonic composition. As early as 1949, Bernstein and his friends Jerome Robbins (the choreographer) and Arthur Laurents (the librettist) batted around the idea of creating a musical retelling of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, set amid the tensions of rival social groups in modern New York City. The project took a long time to find its eventual form. An early version involving the doomed love affair between a Jewish girl and a Catholic boy on New York’s Lower East Side (tentatively titled East Side Story) was altered to reflect the more up-todate social issue of gang warfare. Much of the composition was carried out more or less concurrently with Bernstein’s work on his operetta Candide. It was while working on these projects, in November 1956, that Bernstein was named Joint Principal Conductor of the New York Philharmonic, an appointment that not only revivified a relationship with the Orchestra that had been dormant for the preceding few years, but also placed him in a position to succeed Dimitri Mitropoulos as the Philharmonic’s Music Director, an eventuality that would take place in September 1958. As the production of West Side Story moved into the home stretch it was beset with several crises. Cheryl Crawford, the producer, got cold feet about what she termed “a show full of hatefulness and ugliness,” but her partner, Roger Stevens, jumped in to ensure that the project would continue. Also, the young Stephen Sondheim, who had been brought on as lyricist, snagged the interest of From the Digital Archives – A Valentine for Lenny The World Premiere of the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story took place at a special Valentine concert for Leonard Bernstein on February 13, 1961. The New York Philharmonic was in an extremely celebratory mood, and pulled out all the stops to honor its then Music Director with a program of his own music, a tribute that was said to have been reserved previously for the likes of Beethoven, Brahms, and sometimes Wagner. Bernstein sat in the first tier box for the concert at Carnegie Hall while his good friend Aaron Copland led the opening work — the Overture to Candide. Lukas Foss then took over the podium, conducting the Symphonic Dances premiere — with its “Mambo!” shout out by the musicians. The New York World Telegram reported that the “work revealed what new strength and vitality Mr. Bernstein had brought to Broadway,” as well as to the symphonic concert hall. It was a time of momentous expectations; the Orchestra had announced the previous week that Bernstein’s contract would be extended for another seven years, filming for the movie version of West Side Story was underway, and Symphonic Dances was a hit. Program cover for the special concert, 1961 To read a Philharmonic contributor’s Valentine message to Leonard Bernstein and the Orchestra, scan here or visit the New York Philharmonic Leon Levy Digital Archives at archives.nyphil.org. APRIL 2014 | 27 04-22 Gershwin_Layout 1 4/3/14 11:03 AM Page 28 his friend Harold Prince to be involved as a producer. To everyone’s amazement, Robbins announced at the 11th hour that he would rather spend his time directing than choreographing the show, thereby jeopardizing Prince’s participation; in the end, Robbins was persuaded to stay on as choreographer and was granted an unusually long rehearsal period as an inducement. On August 19, 1957, West Side Story opened in a tryout run in Washington, D.C., with a host of government luminaries in attendance. (During the intermission Bernstein ran into Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who was in tears.) It proved a solid hit when it reached Broadway the next month, running for 772 performances, just short of two years. After that it embarked on a national tour and eventually made its way back to New York in 1960 for another 253 performances, after which it was released as a feature film in 1961. “The radioactive fallout from West Side Story must still be descending on Broadway this morning,” wrote Walter Kerr, critic of the Herald Tribune, in the wake of the opening in New York, and one might argue that his assumption remains true nearly six decades later. West Side Story stands as an essential, influential chapter in the history of American theater, and its engrossing tale of young love against a background of spectacularly choreographed gang warfare has found a place at the core of American culture. In the opening weeks of 1961 Bernstein revisited his score and extracted nine sections to assemble into what he called the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story. The impetus was a gala fund-raising concert for 28 | NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC the New York Philharmonic’s pension fund, to be held the evening before Valentine’s Day. The event was styled as an overt love-fest, celebrating not only his involvement with the orchestra up to that time but also the fact that he had agreed that month to a new contract that would ensure his presence for another seven years. In the interest of efficiency, Bernstein’s colleagues Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal, who had just completed the orchestration for the film version of West Side Story, suggested appropriate sections of the score to Bernstein, who re-ordered them in a new, uninterrupted sequence derived from a strictly musical rationale. Two of the most popular favorites of the musical’s songs are found in the pages of the Symphonic Dances: “Somewhere” and “Maria” (in the Cha-Cha section). Instrumentation: Overture to Candide calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two B-flat clarinets plus E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, snare drum, tenor drum, bass drum, harp, and strings. Symphonic Dances from West Side Story employs three flutes (one doubling piccolo), two oboes and English horn, two clarinets, E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, congas, drum set, guiro, police whistle, tambourine, wood block, bongo drums, cowbell, finger cymbals, maracas, tenor drum, triangle, xylophone, chime, cymbals, gong, orchestra bells, timbales, vibraphone, harp, celeste, and piano.