Report on Inchoate Offences - the Law Reform Commission of Ireland

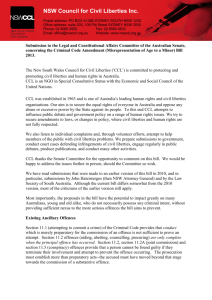

advertisement