The MASSACHUSETTS INNOVATION ECONOMY ANNUAL INDEX

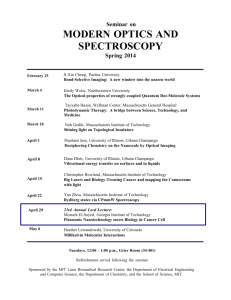

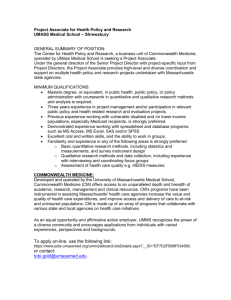

advertisement