CMA Presents Make Art (In) Public

advertisement

CMA Presents Make Art (In) Public An introduction to artists in the public realm 33 1 May 4, 1958 — February 16, 1990 “My contribution to the world is my ability to draw. I will draw as much as I can for as many people as I can for as long as I can. Drawing is still basically the same as it has been since prehistoric times. It brings together man and the world. It lives through magic.” Keith Haring’s introduction to art began at the age of four when his father would entertain him by drawing funny cartoon animals. Together they would draw circles and from the circles develop dragons, dogs, worms, and other such animals— imagery that would inspire his future work. In 1978, at the age of 20, Keith moved to New York City to attend the School of Visual Arts (SVA). His first two years in the city were extremely important and helped form his ideas about making art public. In school, he studied video, performance, and semiotics (the science of signs and symbols). Outside of school, he made new friends, visited museums and galleries, and organized his own art shows. He also hung out with young graffiti artists, whose art he admired for “the obvious mastery of drawing and color, the scale, the pop imagery, the commitment to drawing worthy of risk and the direct relationship between artist and audience.” It was this perfect combination of what Keith learned in school and outside of school that set the trajectory for his public art career, which took off in 1980 when he started drawing with chalk on blank advertising panels in the New York City subways. “In 1980, I returned to drawing with a new commitment to purpose and reality. If I was going to draw, there had to be a reason. That reason, I decided, was for people. The only way art lives is through the experience of the observer. The reality of art begins in the eyes of the beholder and gains power through imagination, invention, and confrontation.” Keith pursued the rest of his career with the same idea that “art is for everybody.” He traveled the world creating murals for public spaces as well as raising awareness about the social issues of his time: nuclear proliferation, anti-apartheid, and AIDS. He often volunteered at children’s organizations, hospitals, and schools to host drawing workshops or create murals for and with kids, always encouraging their self-expression through art. 2 Keith Haring Portrait of Tseng Kwong Chi c. 1985 Sumi ink on paper Courtesy of Muna Tseng Tseng Kwong Chi was a close friend of Keith Haring and an important part of the 1980s downtown arts scene. After the two met in 1979, Kwong Chi quickly became Keith’s “official” photographer, documenting just about every major project Keith embarked on. Some of their most prominent collaborations included Art in Transit, an exhibition and catalog showcasing Kwong Chi’s photographs of Keith’s chalk drawings in the New York City subway system, and Bill T. Jones Body Painting with Keith Haring, a photographic series of the dancer/choreographer Bill t. Jones body painted in white acrylic lines. In addition to documenting Keith’s work, Kwong Chi also took portraits of his contemporaries, including Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Julian Schnabel, Madonna and Kenny Scharf. 3 Tseng Kwong Chi Subway Drawings 1980–86 PHotogRaPHS By tSeng KWong CHI. © Muna tSeng DanCe PRoJeCtS, InC. neW yoRK. aRt By KeItH HaRIng. © KeItH HaRIng founDatIon, neW yoRK. In 1980 Keith started drawing on the blank advertising panels of the New York City Subway system. At first Keith told no one, but once Kwong Chi found out he volunteered to document the work and did so religiously. For the next several years, Keith would call Kwong Chi after riding the subway and Kwong Chi would trace his path, photographing the works themselves, as well as documenting interactions between the works and the public. 4 Tseng Kwong Chi New York City Pop Shop Interior and Billboard 1986 PHotogRaPHS By tSeng KWong CHI. © Muna tSeng DanCe PRoJeCtS, InC. neW yoRK. aRt By KeItH HaRIng. © KeItH HaRIng founDatIon, neW yoRK. Although clearly more a commercial venture, Keith saw the Pop Shop as an extension of his subway drawings. The idea was to continue a direct communication with the public and to create a place where both collectors and kids could come. 5 Tseng Kwong Chi Free South Africa Advocacy 1985 PHotogRaPHS By tSeng KWong CHI. © Muna tSeng DanCe PRoJeCtS, InC. neW yoRK. aRt By KeItH HaRIng. © KeItH HaRIng founDatIon, neW yoRK. Keith originally created the free South Africa image as a painting, but later felt that it was powerful enough to raise awareness of the anti-apartheid movement in the form of posters, buttons, and stickers. 20,000 posters were given away by Keith at an event in Central Park. 6 Tseng Kwong Chi Collaborative Mural with Chicago Public School Students 1989 PHotogRaPHS By tSeng KWong CHI. © Muna tSeng DanCe PRoJeCtS, InC. neW yoRK. aRt By KeItH HaRIng. © KeItH HaRIng founDatIon, neW yoRK. Sponsored by the Chicago Public School system and the city’s Museum of Contemporary art, Keith collaborated on a 520-foot mural with 300 high school students over the course of four days. In commemoration of the event, Mayor Richard M. Daley proclaimed Keith Haring Week and a documentary was made by WTTW-TV called Off the Wall with Keith and the Kids. 7 Tseng Kwong Chi Mural for the Boys Club of New York 1987 PHotogRaPHS By tSeng KWong CHI. © Muna tSeng DanCe PRoJeCtS, InC. neW yoRK. aRt By KeItH HaRIng. © KeItH HaRIng founDatIon, neW yoRK. 8 b. June 13, 1935 (Christo) June 13, 1935 — November 18, 2009 (Jeanne-Claude) When Christo & Jeanne-Claude’s project The Gates was finally unveiled to the public in Central Park on February 12, 2005 it had been over 25 years since Christo’s first sketch for the project and more than 40 years since the team initially proposed a large public artwork for New York City. The incredible amount of time and energy it took to bring the project to life becomes even more incredible when you consider that The Gates was on display for only 16 days before it was taken down and the materials were recycled. For Christo & Jeanne-Claude, the process of making their projects is as important as the final product. Whether they are planning to wrap an entire building with fabric, stack thousands of oil barrels, or install colorful umbrellas simultaneously in Japan and the USA, each artwork begins with finding the perfect location. Once selected, maps and photographs are made of the site, which become the basis of Christo’s preparatory drawings. These drawings are then exhibited and sold in order to raise money and awareness for the project. After planning every single detail of the artwork, the artists then have to convince the community to support it, a process that can take anywhere from months to years and includes hundreds to thousands of people. The projects are special for many reasons, but perhaps most of all for the amount of imagination they ask of their audiences. Before the artwork exists in reality, the public has to see and believe in the artists vision; and after the work is removed, the project stays alive through the memories of the people who were involved in it. In describing their art, Christo said, “all of our projects have this fragile quality. They will be gone tomorrow. They will be missed.” Both born on June 13, 1935, Christo and Jeanne-Claude were destined to make art together and did so for more than 40 years. In that span of time the artists made 22 monumental temporary public works, raised and spent countless millions of dollars to finance their projects, and touched the lives of innumerable people with their art. After Jeanne-Claude’s passing in 2009, Christo continues to pursue their art with Over The River, Project for the Arkansas River, State of Colorado. 9 Christo The Gates, Project for Central Park, New York City, Drawing in two parts 2004 Signed poster 10 Christo and Jeanne-Claude The Gates, Central Park, New York City 1979–2005 Signed photographic poster Photograph by Wolfgang Volz For 16 days in mid-February 7,503 gates with saffron colored fabric were installed in Central Park. Each gate was 16 feet tall and varied in width from 5 feet 6 inches to 18 feet. The project was entirely financed by the artists and was inspired by the interplay between the winding walkways of Central Park and the city blocks surrounding it. 11 Christo Surrounded Islands, Project for Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida, Drawing in two parts 1982 Signed poster 12 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Surrounded Islands, Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida 1980–83 Signed photographic poster Photograph by Wolfgang Volz For two weeks in early May of 1983 eleven islands in Biscayne Bay were surrounded with floating pink fabric that extended 200 feet from each island. As with all of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s artworks, the project took many years to complete and included thousands of people. Surrounded Islands was entirely financed by the artists and was inspired by the way inhabitants of Miami live between land and water. 13 Christo and Jeanne-Claude Wrapped Reichstag, Project for Berlin, Collage in two parts 1984 Signed poster 14 Christo and JeanneClaude Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin 1971–1995 Signed photographic poster Photograph by Wolfgang Volz For 14 days the Reichstag, a symbol of democracy in Berlin, was wrapped in thick polypropylene fabric with blue polypropylene rope. The project was entirely financed by the artists and inspired by the history of the Reichstag, as well as the use of fabric throughout art history. The wrapping highlighted the majestic features of the building in a way that revealed the essence of the Reichstag. 15 May 26, 1916 — September 8, 1999 Known as “The Viking of 6th Avenue,” Moondog, whose real name was Louis, is one of New York’s most legendary street performers. Between the years of 1949 and 1974 he was a regular sight on the streets of Midtown, and one not to be missed. At over six feet tall and dressed in handmade Viking attire, Moondog captivated people with his eccentric appearance. But the way Moondog looked was only the very surface of his unique creative genius. Blinded at the age of 16 by a discarded dynamite cap he found on the railroad tracks near his home in Hurley, Missouri, Louis worked hard to overcome his new disability. He learned Braille quickly, began to write poetry, and studied music theory, piano, pipe organ, percussion, violin, and viola. Louis was able to learn a new instrument almost every month and indeed later in his career said that he was “studying every instrument in the orchestra” so that he could “record a whole symphony himself.” By the time Louis moved to New York City and reinvented himself as Moondog, he was not only composing his own music, but he was making his own instruments too. Endlessly experimental, Moondog invented percussion and string instruments with names such as The Dragon’s Teeth, Trimba, Oo, Utsu, and Uni. He performed on the streets nearly every day, rain or shine, and as the public learned more and more about this interesting person, his career quickly blossomed. By early 1950 Moondog had started making albums, recording both on the street with the sounds of taxis and tugboats accompanying him, and in the studio with 40 piece orchestras. As his renown grew, famous musicians and celebrities like Duke Ellington, Dean Martin, Leonard Bernstein, Charlie Parker and Cassius Clay came to watch Moondog perform. He even jammed on the bongos with famous actor Marlon Brando. Much like the diversity of the city’s inhabitants, Moondog’s music is a blend of all cultures. He combined Native American and Cuban drumming with classical composition, jazz, and endless other influences from all over the world. The result is a completely unique kind of music that will always sound ahead of the times. 16 CMA Teaching Artists Mandy Talbot and Michelle Zahabian Moondog 2011 Fiberglass, terracotta, oil paint, assorted fabrics, human hair, wood and iron This life-size replica of Moondog was created to resemble the artist circa 1974 when he left New York City to live in Germany. Using their unique skills, Mandy sculpted terracotta to create Moondog’s face and hands and Michelle designed Moondog’s clothing from close observation of the artist’s own clothingmaking techniques. The steel spear was forged and fabricated with a wax coating by Jim Poulimas. 17 b. December 3, 1977 “I feel like no matter where I am and no matter what I am doing I am always going to be thinking about how to make people’s lives a little bit different.” Every public artist in one way or another must address the fact that their work will be seen by the community. It goes with the territory. If you make art in public spaces, the people who use the space will have something to say about it. This is the beauty of the medium: direct communication between artist and audience. For most, this communication is enough, but for Caledonia Dance Curry (otherwise known as Swoon) it is only the beginning. Swoon takes a more intimate approach to the idea of community. Her art doesn’t simply “involve” a community, but pushes further in order to build as well as connect communities. This ethic has informed her entire career, and especially so in recent projects such as Konbit Shelter, a set of sustainable homes and community centers for earthquake victims in Bigones, Haiti and The Dithyrambalina, a permanent sculpture for New Orleans in the form of a life-size musical house that visitors can play. These projects and others like them display Swoon’s personal practice of involving the community in her artwork, and in turn, becoming involved in the community as well. Both whimsical and political, Swoon seems to use two parts of her brain when making art. On the one hand, her work confronts serious subjects like water rights in Bolivia and violence in Mexico. On the other hand, she has also organized pure public art fun such as junk-band parades, pirate takeovers of the Staten Island ferry, and awesome adventure trips on handmade rafts. The message being that you do not have to censor who you are. Your art can be silly, serious, personal, political or whatever you please and it is through this kind of uninhibited creative expression that connections are created between people and communities come together. 18 Swoon Thalassa 2011 Block print on mylar with coffee stains and gouache paint Originally created as an installation for the New Orleans Museum of Art, Thalassa is a sea goddess who is often considered the mother of all sea creatures. Swoon envisioned the piece as a way to define human’s relationship with nature, as well as New Orleans’ relationship with water. 19 b. January 3, 1985 “I love people who are passionate about things. I also love bright colors.” Street performers often adopt not only pseudonyms, but also entire personas. Translated from Spanish, Tranqui Yanqui means “Chill American” and is the alter ego of Nick Mahshie, a Miami-born, Buenos Aires-based artist. As Tranqui, Nick creates cardboard clothing colorfully painted with imagery that merges American popular culture, Latin icons, and the tropical symbols of his native Miami. This “wardrobe” is not only the costume Tranqui assumes in his public performances, but also makes up the products he attempts to sell people at ferias (street markets) throughout the city. Whether it is a closet full of Tranqui attire, an ATM dispensing Tranqui-Bucks, or a Tranqui American Sueno Stand, the scenarios Tranqui Yanqui creates to engage the public in his world are ideas that begin in the heart and build in the mind. Like a good salesman, Tranqui excites his customers’ eyes with bright and colorful products (literally, eyes sometimes get wider). But like a magician, the colors are more of a distraction, so that while you’re looking at the products he can communicate with you on a personal level about who you are, where you come from, and what your life is like. In this way, the art is a vehicle to invoke the curiosity of passersby, initiate dialogue, and bond with people across cultural borders. 20 Tranqui Yanqui Tranqui’s Sueño Americano 2011 Acrylic paint on cardboard, wood, and found materials Tranqui’s Sueño Americano is an interactive stand designed to be an inviting call to partake in Tranqui’s fantasy world. Colorful hats, glasses, and necklaces made of paper and cardboard are items created to transport you to another place. This art is made to be seen, touched, and enjoyed. The costumes on display have been used by Tranqui and other participants of Tranqui’s “Sueño” during one of his many live performances. 21 December 15, 1928 — February 19, 2000 “Just carrying a ruler with you in your pocket should be forbidden, at least on a moral basis.” An Austrian artist, architect, environmentalist, and activist, Hundertwasser tirelessly pursued man’s right to live in harmony with nature. He advocated tenant rights for trees, campaigned against the straight line in architecture, and brought his vision for a better world to the public with printed manifestos, public demonstrations, and actually creating the kind of architecture he preached. Although Hundertwasser did not create his first building until he was 55, he had been forming his ideas about architecture since the very beginning of his career. His philosophy centered on the idea that “the straight line is not a creative line, it is a duplicating line, an imitating line,” which he explained in his Mouldiness Manifesto Against Rationalism in Architecture (1958). This belief was formed from the observation that straight lines do not appear in nature, and so it would be unnatural to use them architecture—in fact it would crush the human spirit. Unfortunately, almost all of the buildings that Hundertwasser saw being created around him used straight lines. In response, as “Architecture’s Doctor,” Hundertwasser designed his buildings to have uneven floors, irregularly laid tiles, trees coming out of windows, and roofs covered with earth, grass and even more trees. He also supported each tenant’s right to paint anything they wanted within arm’s reach outside their windows. These could be the only solutions for bad architecture. Hundertwasser’s commitment to his ideas is evident in the amount of art he created. Beyond the hundreds of paintings, drawings, flags, and smaller artworks, there are 35 living, breathing architectural works that display all of Hundertwasser’s philosophies on living in harmony with nature and art. But sometimes it is the things Hundertwasser said that mean the most. When describing the uneven floor in the hallways of the Hundertwasser House, he said, “the uneven walkway becomes a symphony, it is a melody for the feet. The walkway makes the whole person vibrate. Architecture should elevate man, not humiliate him.” 22 Friedensreich Hundertwasser Hundertwasser Turm (Tower) 1999 Developer: Brauerei zum Kuchlbauer gmbH, Leonhard Salleck, Abensberg Planning: Peter Pelikan (preliminary plan dating from June 1999) Model 1:50: Alfred Schmid, 2000 The seventy metre tower was originally planned for various uses such as a planetarium, a cinema, and a commercial space but was finally realized as an exhibition space where the concept and philosophy of the Kuchlbauer Brewery would be represented. Due to unfortunate refusal from the Bavarian department for the protection of historical heritage (Bayerisches landesamt für Denkmalschutz) this tower project had to be reduced after Hundertwasser’s death to 35-metre height. 23 Friedensreich Hundertwasser Textile Factory Rueff Truck 1989 Collage on paper C-print on sintra panel 24 Friedensreich Hundertwasser Suggestions for Healing of Architecture 1971–72 Watercolor on three architectural photographs C-print on sintra panel Hundertwasser describes the artwork in his own words: “I took photographs of a completely hideous, terrible highrise residential project in north Germany—I think it was built by “neue Heimat” (“new Homeland”)—and painted trees, non-regulated irregularities and windowright activities over them, just the way I imagine the activity of the architecture doctor who heals sick buildings.” 25 Friedensreich Hundertwasser Suggestions for Healing of Architecture 1971–72 Watercolor on three architectural photographs C-print on sintra panel Hundertwasser describes the artwork in his own words: “I took photographs of a completely hideous, terrible highrise residential project in north Germany—I think it was built by “neue Heimat” (“new Homeland”)—and painted trees, nonregulated irregularities and window-right activities over them, just the way I imagine the activity of the architecture doctor who heals sick buildings.” 26 Friedensreich Hundertwasser Tree Tenant 1976 Ink and watercolor on paper C-print on sintra panel Hundertwasser believed that trees should be given tenant rights both on top of buildings and actually inside of apartments. In his essay Tree Tenants are the Ambassadors of the Free Forests in the City (1980) he wrote, “the tree tenant is a giver. It is a piece of nature, a piece of homeland, a piece of spontaneous vegetation in the anonymous and sterile city desert, a piece of nature which can develop without the rationalist control of man and his technology.” In advocating for tree tenants he made demonstrations and coined the phrase “each additional tree—an additional chance.” 27 Friedensreich Hundertwasser Drawing of the Green Motorway Ink and watercolor on paper C-print on sintra panel In this design Hundertwasser outlines his idea for an inaudible and invisible green motorway. The concept was to create highways that were less disturbing for houses and people near the roadway, as well as a more pleasurable experience for drivers. 28 b. December 30, 1978 Creating his artist name from the idea of art as a remedy, Guillaume Alby pursues a specific purpose when he makes art in public: Peace. Love. Unity. These are the feelings and ideas that Remed wants to convey to his audience, and he does so with massive murals in far-flung places like Gambia, Sao Paolo, Ukraine, Atlanta, New York, Portugal, and Spain. “I create rhymes of colors, shapes and sounds so as to express an emotion, a feeling, or the evolution of thought. I paint as you write a diary, a notebook of inventions, or philosophical novel. Every time, I make my self-inventory. Art is for me the sincere blend of science and Soul. I live what I feel, I paint what I live.” Remed’s subject matter is almost always the human figure, which he uses to explore ideas about existence and creation. His figures exude strength, express hope, and confront adversity. Their main body parts are made up of simple forms that when viewed as a whole harmonize in a delicate interplay of color, shape and texture. 29 Remed Heart the World 2011 Spray and acrylic latex paint on MDF This piece was created specifically for CMA’s Make Art (In) Public exhibition. At the end of the show it will be de-installed and a permanent home will be found for it where the public can view it. 30 Children’s art comes in all different forms and in the 1970s teenagers began creating their art in “piecebooks”. Combining the idea of a masterpiece and a sketchbook, piecebooks emerged out of a growing desire by fans and practitioners of the art to collect the signatures, or “tags,” of their fellow artists. Unauthorized graffiti writing is and always has been illegal, but over the years the beautiful colors, intricate designs, and bold social statements have proved greatly influential to contemporary artists and culture. The current fascination with the graffiti movement, and the piecebooks that were an important part of it, is recognition of this bold lettering as a form of art. While issues like how often the tag was seen and how difficult it was to make were part of the appreciation, the merit that received the most attention was the actual visual artistry of the tag. Experiments in line, color, value, and shape sparked innovation in letterforms, characters, and subject matter, all of which helped these kids grow creatively. Thanks to former graffiti artist George Sewell we are able to get a glimpse into the early formation of this hugely influential art form, as well as the creative development of artists like TEAM and FAME. 31 George Sewell and Nelson Keene Carse Untitled Piecebooks 1976–1984 Rapidograph and design markers on paper George Sewell Untitled 1978 C-print on sintra panel Rapidograph and design markers on paper George Sewell The Mind Boggler 1976 C-print on sintra panel Rapidograph and design markers on paper 32

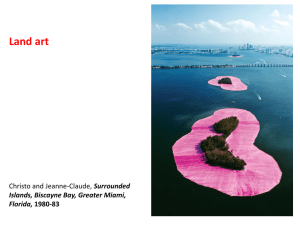

![[#SWF-809] Add support for on bind and on validate](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007337359_1-f9f0d6750e6a494ec2c19e8544db36bc-300x300.png)