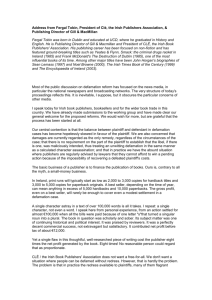

small town police forces, other governmental entities and the

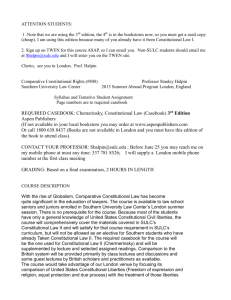

advertisement