Color Cinematography - Christopher Chomyn, ASC

advertisement

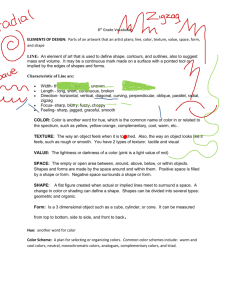

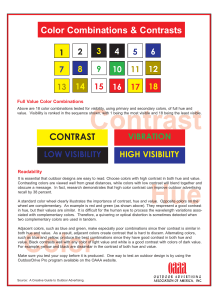

Color Cinematography Color cinematography utilizes all of the same photographic principles as monochromatic cinematography while adding to the equation the emotional and expressive power of color. The most effective and dramatic results seem to be realized when color images utilize the same basic principles of contrast and lighting as are used in monochromatic imagery while exploiting the added components of color design, psychology, behavioral conditioning. Working With Color Our sensation of color depends primarily on the composition of light, the wavelengths that the subject reflects and the reaction of our cones which respond to the radiating energy. The light can be pure, of one specific wavelength, or it can be a mixture of wavelengths. The dominant wavelength is the HUE and the degree to which the hue dominates is known as CHROMA or saturation. LUMINANCE describes the brightness of a color. hue refers to the color value in terms of the three additive primary colors: red, green, blue -- and the three secondary colors (or subtractive primaries): cyan, magenta, yellow. (What color is it? To which pure color is it closest in quality?) chroma refers to the saturation or purity of color. (How red is it?) When a color is combined either with black, white or another color, its chroma is reduced. luminance refers to the brightness or amount of white in the color. Copyright © 1997 & revised 2005 Christopher Chomyn page 71 Contrast Our perception depends on contrast. A stone appears small when viewed next to a boulder, and large when seen next to a pebble. Similarly, we can see light because of dark and dark because of light. Color also relies on contrast to reveal its nature. In his book, “The Art of Color”, Johannes Itten describes the seven kinds of color contrast: 1. 2. 3. 4. Contrast of Hue Light-Dark Contrast Cold Warm Contrast Complimentary Contrast 5. Simultaneous Contrast 6. Contrast of Saturation 7. Contrast of Extension The following is a summary of Itten’s comments on contrast: 1. Contrast of hue simply refers to the contrast of colors at their most pure and intense state. Looking at the additive primaries and their compliments (the subtractive primaries) reveals the most obviously contrasting hues. Red/Cyan Green/Magenta Blue/Yellow The intensity of contrast of hue is reduced as the hues used are removed from the primaries by reducing the chroma (saturation or intensity) 2. Light-dark contrast is the most fundamental contrast known to nature (day and night). White and black are complete opposites. White contains all the wavelengths that comprise the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum and black is the absence of all light. All the shades of gray exist somewhere in conflict between light and dark. Copyright © 1997 & revised 2005 Christopher Chomyn page 72 3. Cold-warm contrast refers to the way in which colors affect us emotionally, and not with regard to actual temperature. Orange/Yellow are warm colors and magenta, blue and cyan are cool colors. Compositionally speaking, cool colors tend to recede while warm colors appear to approach the viewer. Claude Monet observed that light and shade, reflection and refraction resolved the color of objects into elements of cold and warm as well as variations of light and dark. Notice in the following paintings that the cool blue of the sky is in contrast, as a shadow color, to the warm tones of the sunlight. 4. Complimentary contrast refers to the most extreme color contrast. In pigments (subtractive color theory) complimentary colors combine to make black. In light (additive color theory) complimentary colors combine to create white. When complimentary colors are adjacent to one another, they “incite each other to maximum vividness, when mixed they annihilate each other, reducing the chroma value to nothing.” 5. Simultaneous contrast results from the fact that for any given color the eye simultaneously requires the complimentary color, and will generate it spontaneously if it is not already present. The presence of this simultaneous complimentary color is purely a sensation in the eye of the viewer and is not objectively present. It cannot be photographed. Select one colored square, cover the other two squares and look closely at one colored square. The gray insert will appear to take on the complimentary hue. Against red, the gray will appear Copyright © 1997 & revised 2005 Christopher Chomyn page 73 cyan, against green, the gray will appear magenta, against blue, the gray will appear yellow. The significance of this is that there is no actual difference in the gray inserts. 6. Contrast of Saturation relates to the purity of hue or chroma of a color. This is the contrast between pure intense colors and dull or diluted colors. The hues produced by the dispersion of white light are colors of maximum saturation or intensity. Colors become less saturated, less pure when they are diluted with white or black or when mixed with their complimentary colors. When working with light and photography, a hue that is pure and is photographed at key will be the most saturated. When the exposure is either increased or reduced, the intensity of the hue will be altered in proportion to the variation in density as depicted on the film’s characteristic curve. 7. Contrast of Extension relates to the contrast between two areas of varying size within the composition. The two factors that determine the force or impression of a pure color are its brilliance and its extent. To determine brilliance, one must compare the colors to a neutral gray background of medium brilliance. An 18% gray or middle gray card works well for this purpose. When we do this, we can see that the intensity or light values of the primary and secondary hues are different. Goethe set up approximate numerical ratios for these values based on his own experiences. Goethe’s light values are: yellow orange red violet blue green 9 8 6 3 4 6 If we remember that Goethe was working with pigments and not light we understand that yellow and violet are opposite on the color wheel. Here we can see that yellow and violet. Both of maximum purity (intensity) will have different apparent luminance values. Goethe determined: “ Given equal hue, yellow will appear brighter than any of the other colors. Therefore, yellow in a composition will command more attention. If one seeks to create harmony and balance, then one must reduce the area of yellow using the reciprocal values to determine the correct proportions. In other words, yellow is three times as luminous as violet, so one would expect that yellow would occupy 1/3 the area of its compliment, violet (if one intends to create harmony and balance).” This can be used to great effect. When two colors that share luminosity such as red and green are used in disproportion, the color which is over-represented generates an exciting luminosity of its complimentary red in the eye. Remember that simultaneous contrast asserts that the eye demands the compliment to a hue. Similarly, contrast of extension causes the minority color to appear more vivid than if it were present in harmonious proportion. Copyright © 1997 & revised 2005 Christopher Chomyn page 74 Color Perception Our perception of color depends on more than the wavelength of the light, it is also affected by that which surrounds it. If the surrounding area is filled with color, the various color contrasts will affect our perception. If the surrounding area is void of color but represents contrasts of light and dark, our perception will also be influenced. The surface off which light reflects and the angle of the light will also alter our perception of a color. Is the surface specular or diffuse? A specular surface reflects hard light with sharply defined highlights. These highlights will present as white or near white reflections. This will result in desaturation or a reduction in chroma. A diffuse surface reflects softer light, with less well defined highlights. This will reduce the intrusion of white into the colors present and will help to keep the colors closer to their pure state. By not diluting the colors with the intrusion of white highlights, the saturation or chroma will remain unaltered. Similarly, frontal lighting will tend to reveal greater saturation than will light coming from an acute angle. This can be attributed to the efficiency of reflection. Think of a ball bouncing off a wall. When you throw the ball at the wall, it must come to a complete stop before it can bounce back to you. Light can be said to function in a similar manner. Front light, must reach its subject (some light will be lost due to absorption), come to a stop and then reflect off the subject back to the source. Light falling on its subject from an acute angle (much like the ball in our previous analogy) will not come to a complete stop as it reflects off the subject toward the camera. Instead, it merely glances off the surface, changing direction only slightly and so it is able to maintain much of its original momentum and therefore it’s intensity is recorded as brighter. As exposure increases, the negative increases in density and the resulting positive image renders a less saturated (more white) highlight. Copyright © 1997 & revised 2005 Christopher Chomyn page 75 While the angle of incidence can affect how the quality of light is perceived, the actual quality of the light falling on and subsequently reflecting off a surface will also have an affect on our color perception. Hard front light can create specular reflections in an otherwise diffuse surface while soft light creates more diffuse reflections. And so will affect our perception of the color of light reflecting of the object. Specular highlights may cause us to perceive colors as less saturated than diffuse highlights. Beyond the physical lies our social and psychological conditioning. Many studies have demonstrated the relationship between specific wavelengths of light and our perception as well as their effect on human behavior. It is likewise a reality that relationships can be established, to which we lend meaning. We can then exploit this information in the course of our film making. By establishing a color palette in relationship to characters, locations or situations, we can systematically set up expectations in the mind of the audience each time the audience is reintroduced to these colors. This works in much the same way as the classical conditioning which Pavlov demonstrated in his experiments with his dogs where he created a pattern of sound with feeding so the dogs would associate meal time with the sound of a bell, thus eliciting a physical behavioral response to the sound of the bell by establishing the expectation of food even when food was not present. In this way we can use our learned associations with specific colors to build and release tension. The color we work with can be colored light or the colors used in set decorating and costuming. We can also modify locations to accommodate our color design. It is essential for the cinematographer to work closely with the production designer in order to maintain consistency in the design and execution of the color palette. Yet another way to think about color comes to us from the abstract expressionist, Wassily Kandinsky who believed that each color has an analogue in shape, a shape to which it is best suited. Yellow is a sharp color and so is best suited to the sharp shape of a triangle. Blue on the other hand is soft and deep so its ideal shape would be a circle. This seems to correlate somewhat with the ideas expressed by Goethe when he assigned values to each color, as described above. Copyright © 1997 & revised 2005 Christopher Chomyn page 76 These paintings by Kandinsky help to provide a visual representation of how he put his theories to practice. In addition to identifying colors with specific shapes, Kandinsky compared color to music. He said, ``Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.'' Kandinsky claimed that when he saw color he heard music. This led him to use color in a theoretical way associating tone with timbre, hue with pitch, and saturation with the volume of sound. Copyright © 1997 & revised 2005 Christopher Chomyn page 77